eBook - ePub

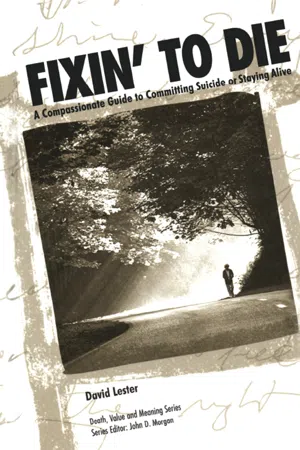

Fixin' to Die

A Compassionate Guide to Committing Suicide or Staying Alive

This is a test

- 174 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is a guide to making and carrying out the psychological decision to kill oneself or, if one so decide, to continue living. It focuses on the decision to commit suicide than on the decision to continue living.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fixin' to Die by David Lester, PhD. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 4

How Do You Want To Die?

We are all going to die. Of this there is no doubt. The critical question we must ask ourselves is, therefore, not “Do we want to die?” but rather “How do we want to die?”

Consider this question. How do you want to die?

Think about it. Write it down on the remainder of this page.

Have you ever had fantasies of how you might die? Have you ever had daydreams about dying?

When I was a teenager, I daydreamed about dying in a heroic sacrifice—being gored by a charging bull so that others would live. Or going off to the Belgian Congo (now called Zaire) to fight for the rebels against a totalitarian government.

What are your fantasies of how you might die?

Many people have told me that, when they die, they want to feel no pain and they want to be asleep at home in their own bed.1 Unfortunately, all of the people who die in car crashes, from horribly painful terminal diseases or at the hands of murderers, perhaps away from home, in the street or in a hospital—that is, most people—will not die at home in their own bed, asleep, and without pain.

Most of us do not think about this hard reality until it is too late. As a result, most of us will not have the kind of death we want, and the chances are good that we will have just the kind of death we don’t want. Therefore, now is a good time to start thinking about your death, whatever your age. How do you want to die? And what would you consider to be a “good” death?

THE CONCEPT OF AN APPROPRIATE DEATH

When psychologists consider the question of what is a good death, they talk about an “appropriate” death rather than a “good” death. A good death is what “euthanasia” means literally, and the term euthanasia now has acquired a variety of connotations which can upset people—for example, it has become associated with “mercy killing,” that is, killing someone to end their misery, not necessarily with their permission or agreement.

My aim is this chapter is to have you think about what a good or an appropriate death would be for you. To help you think about this, I will describe some of the ways in which scholars in the field of death and dying have defined the concept. The list is not exhaustive—I am sure that other definitions can be proposed. I will present you with some possible definitions simply to stimulate your thinking on the issue.

WEISMAN AND HACKETT’S DEFINITION

Although the literature is not very extensive, there are some scholars who have written about the concept of an appropriate death (or dying). In 1961, Avery Weisman and Thomas Hackett wrote an article that brought the concept to the attention of psychiatrists. Weisman and Hackett noted that some of their patients knew, correctly as it turned out, the exact time when they were going to die, and yet faced their impending death without conflict, depression, suicidal ideation, or panic. They did not act like those hexed into death by suggestion (sometimes called “voodoo death”), after which they become hopeless and helpless. On the contrary, Weisman and Hackett’s patients knew that death was inevitable and they desired it. For these patients, death was faced peacefully, calmly, and without apparent worry.

After reflecting on their experiences with these patients, Weisman and Hackett proposed four specific criteria for a death (or a dying process) to be considered appropriate.

1. Most importantly, death must be seen as an event that reduces the conflict in your life or as a solution to problems you are facing. (Alternatively, there may be few conflicts or problems in your life.)

2. Death must be seen as being compatible with your conscience—for example, you don’t view your death as a cowardly act or as a sin.

3. There must be a continuity of important relationships as you die (for example, dying with your loved ones beside you), or there must be some prospect of the relationships being restored (for example, being reunited with loved ones after you die).

4. Finally, you must sincerely desire death.

Because Weisman and Hackett’s criteria for an appropriate death were originally proposed only for deaths from natural causes, they did not include suicide as a possible type of appropriate death. However, I think that a suicidal death can meet each of these four criteria and, therefore, be an appropriate death. You may be facing few problems, or your death from suicide would reduce conflict in your life (criterion 1). Your moral philosophy may enable you to see suicide as an acceptable act (criterion 2). You may expect to be reunited with loved ones after your suicide (criterion 3), and you probably do sincerely desire death (criterion 4).

As I mentioned previously, other writers have proposed different criteria for an appropriate death, and I will list five alternatives, all of which would permit suicide to be viewed as an appropriate death in some circumstances.

THE SIMULTANEOUS OCCURRENCE OF DIFFERENT KINDS OF DEATH

Richard Kalish has identified four types of death—physical, psychological, social, and anthropological—and his classification suggests another criterion for a death to be appropriate. Let me first define his terms.

Biological death is when your organs cease to function, and clinical death is when your organism itself (as a whole) ceases to function. These two forms of death constitute physical death. Biological and clinical death need not coincide in time. For example, it is possible for your organs to keep functioning after your brain has been removed from the body. In this situation, you are clinically dead but biologically alive. In fact, this is what happens when organs are removed from a person who has recently died so that they may be transplanted into others who need them.

You are psychologically dead when you cease to be aware of your own self and of your own existence. You do not know who you are nor that you even exist. A person in a coma is presumed to be psychologically dead.

Social death occurs when you accept the notion that, for all practical intents and purposes, you are dead, and you act as if you are dead. In cases of voodoo death, if you believe that you have been hexed and expect to die in a few days, you prepare for death. You may refuse nourishment and lay down in expectation of death. In this situation, you remain conscious, and so you are not yet psychologically dead, and you are certainly not physically dead.

Social death may also be defined from the point of view of friends and relatives. In this situation, you are socially dead when the people who know you act as if you no longer exist. For example, an elderly relative may be put in a home and forgotten, and the family acts as if she or he no longer exists. The relatives of a hexed individual may start grieving and preparing for the funeral.

The final kind of death, anthropological death, occurs when you are cut off from the entire community, rather than merely your relatives, and treated as if you no longer exist. The Orthodox Jew who marries a Gentile is anthropologically dead to the Orthodox community. The Orthodox community and the person’s family mourn for him just as if he or she were physically dead.

Kalish’s four types of death provide a possible criterion for an appropriate death. These four kinds of death can occur at different times in your life. For example, an elderly parent may be put in a nursing home and forgotten about (social death), later fall seriously ill and become so senile that she or he loses awareness of who she or he is (psychological death), and even later finally succumb to her illness (physical death). In some families, a person may be mourned on several occasions.

A death could be considered appropriate when all four of these different kinds of death coincide in time. When they occur at different times, ethical and logistical issues are often raised. For example, when a person is in a coma, the issue of whether or when life support systems should be turned off may be raised. Thus, a person who falls into a coma (psychological death) and physically dies much later could be viewed as having an inappropriate death. The person who is placed in a nursing home and forgotten (social death) does not die an appropriate death. Consider, for example, how you feel about these situations—lying in a coma for several years, kept alive by machines, or abandoned in a nursing home with no friends or relatives to visit and check that you are receiving good medical attention and not being physically abused. In fact, my mother in England dreaded being placed in a home, with her only child, myself, thousands of miles away in America, unable to check that she was being taken care of. She often said that, if she had to move to a nursing home, she would kill herself. Luckily, she was able to live at home except for the final week of her life, which was spent in a hospital, where she died of cancer.

Using this criterion, suicide could be an appropriate death since all four kinds of death can occur at the same time in a suicidal death.

THE ROLE OF INDIVIDUALS IN THEIR OWN DEATH

Some existentialist writers believe that death is appropriate only when you play a role in it. In other words, a person struck down by chance factors, such as lightning, would not have died an appropriate death. Obviously, suicides play a major role in their own death. When discussing the death by suicide of one of his psychiatric patients, Ludwig Binswanger, an existential psychiatrist, believed that only in her manner of death did she “fully exist.” For Binswanger, we exist authentically only when we resolve situations decisively by our actions. Binswanger’s patient, whom he called Ellen West, was psychiatrically disturbed for most of her life. She was hospitalized on several occasions. Her symptoms dominated her life and restricted her opportunities for growth. In her decision to kill herself, she seemed to be making a choice, and for once she was not overwhelmed by her symptoms or the conflicts underlying her psychopathology. Her choice of suicide was authentic.

In this way, when people play a role in their own deaths by committing suicide, their deaths can be judged as appropriate insofar as they took personal control and accountability for their actions.

PHYSICAL INTEGRITY IN DEATH

Some people feel that a “natural” death is a good death because, in a natural death, the body is physically intact and retains its physical integrity. For example, when a person commits suicide by shooting herself or a murder victim is stabbed to death, the body’s physical integrity is lost, and the death may be considered inappropriate. From this point of view, the death of someone whose life has been prolonged by the use of transplants and medical intrusions into the body cannot be appropriate. Only a death from natural causes without medical intrusion may be viewed as appropriate. Suicide could be appropriate under this criterion if a suitable method is used, such as an overdose of sleeping pills for, in this case, the physiological damage to the body is minimal (and perhaps less than is the case in death from such illnesses as cancer).

CONSISTENCY IN LIFESTYLE

If I were to ask you how you expect or would like to die, your response will reflect something about yourself, your personality and your fears, but it may also reflect your lifestyle, a lifestyle which has developed as a result of your inherited tendencies, experiences, personality, successes, and failures. People will typically choose a death that fits with their lifestyle. The passive person may choose to die from a disease or even at the hands of another. The aggressive person may choose to die in a fight or in war. The self-destructive person may commit suicide.

What did you write down on the first page of this chapter? Does it seem to you that the mode of death you chose is consistent with your lifestyle?

A person’s death may be appropriate, therefore if he or she dies in a way that is consistent with his or her lifestyle For example, Ernest Hemingway’s suicide by a firearm in the face of growing medical and psychiatric illness was consistent with the death-defying lifestyle he had cultivated during his lifetime. Hemingway ran with the bulls in Spain, hunted big game in Africa, and sought to be in the front lines with the soldiers in Europe during the Second World War. He risked his life in all kinds of situations. It would be hard to imagine Hemingway dying as a shrunken old man, drooling in a corner of a locked ward in a mental hospital.

Suicide could be viewed as appropriate, then, if it is consistent with the person’s lifestyle.

Whenever I think about this particular definition of an appropriate death, I think about my own lifestyle. Earlier I mentioned Weisman and Hackett’s observation that some of their patients met death calmly and without anxiety.

A few years ago, I was on my way to a give a talk in Mexico City about euthanasia and assisted suicide. Because the airline on which I was traveling had recently had a plane crash in which all the passengers died, I was more anxious than usual to be flying. After we landed (without incident), I rushed through the airport to meet my hosts and, when I was in their car, I began to worry that I had picked up the wrong suitcase because, in my haste, I had forgotten to check the luggage tag. Perhaps, I had picked up a suitcase that looked just like mine. In fact, I was anxious about one thing or another for most of the trip.

Later, when I stood up to give my talk, I described all of this to my audience and noted that I tend to spend most of my time in a state of mild anxiety, worrying about all manner of things every day. How likely is it, then, that I will meet death without anxiety? I shall probably continue to worry about things, including whether I remembered to change my will and turn the stove off and whether there is a God after all. I am sure that my dying and my death, however caused, will be consistent with my lifestyle. The only way I will not be anxious about dying is if I am in an advanced stage of senility, if I am so sick that my emotions are dulled, or if I am stupefied by medication!

If people have been irrational in their thinking for much of their life, they cannot be expected to be rational when they are dying. If you have raged all your life, then you will probably “rage, rage against the dying of the light,” as Dylan Thomas wrote If you have always been unsure about your decisions in life, then you will probably be indecisive in dying as well.

THE TIMING OF DEATH

Edwin Shneidman (1967) suggested that the timing of our death was an important consideration in defining an appropriate death. Shneidman felt that people are sometimes able to discern that, after a given point, any further life would be a defeat or a pointless repetition. There may be points in time when death seems to be the right thing. For example, the Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima placed great imp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- SOME POINTS TO PONDER

- THE DECISION TO DIE

- Bibliography

- Index