This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This stimulating and challenging work explores how to place consumers in charge to facilitate good patient care. It provides a coherent account of how customer/supply and demand/supply relationships work and identifies and describes the principles of good medical care and the approaches that can be taken to offer a credible and realistic agenda for change. This book is essential reading for policy makers and shapers healthcare managers and all those with an interest in the role of patients in healthcare.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Providing Information for Health by Alan Gillies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Historical evolution

Introduction

This chapter will attempt to show how the current situation in primary and community healthcare informatics has arisen as a consequence of policy decisions made in the past.

History

Up until the late 1980s, GP computing was a minority sport. (Primary care informatics was unheard of.) The reforms implemented in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which resulted in fundholding, the new GP contracts and the internal markets, led amongst other things to a rapid growth in the number of computers found in general practice.

| On-line resource Now view the on-line poster, A comparison of the computerisation of medical practice in the public health sector, accessible in the Chapter 1 section of the website. This was presented in the USA in 1993 (Gillies, 1993). |

I wrote the following account of the situation in 1995.

Introduction

This paper will consider the computerisation of primary healthcare in five sections:

- • the area under scrutiny

- • the methods and sources used

- • the observations

- • the issues identified

- • conclusions.

The area under scrutiny

The UK family health sector

General medical practice is the part of the UK National Health Service (NHS) which patients encounter most often. Over the last seven years, there have been major changes in the organisation and working practices within this sector.

These changes were driven by a number of key pieces of Government legislation (Department of Health, 1986, 1987, 1989):

1986: | Primary Care: an agenda for discussion |

1987: | Promoting Better Health, Government White Paper on Primary Care |

1989: | General Practice in the NHS: the 1990 Contract. |

Prior to 1986, the role of the family doctor was seen as a provider of medicines to tackle simple diseases and a mechanism for referring more seriously ill patients to hospital.

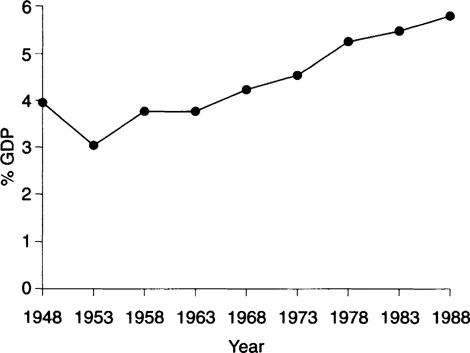

The problem with this approach was the cost. Further, there were few checks on value for money and on the effectiveness of resource management. The NHS budget as a percentage of GDP has risen continually since the 1950s (see Figure 1.1).

In order to attempt to arrest this trend, Government policy laid down in the Promoting Better Health White Paper (Department of Health, 1987) set out the following aims:

- • to focus upon preventive healthcare

- • to require doctors to provide better information to the Family Health Service Authority (FHSA) in order to increase accountability

- • to link doctors’ incomes to performance measured against specific targets.

The reforms set out in these pieces of legislation divided the NHS into ‘suppliers’ and ‘purchasers’ with primary healthcare on the purchasing side and secondary healthcare on the supply side. This is known as the internal market within the NHS.

Figure 1.1 NHS budget as a percentage of GDP. Source: Office of Health Economics, 1989.

Implementing this policy required doctors to improve their information systems dramatically, at the same time as absorbing change in just about every area of their working lives.

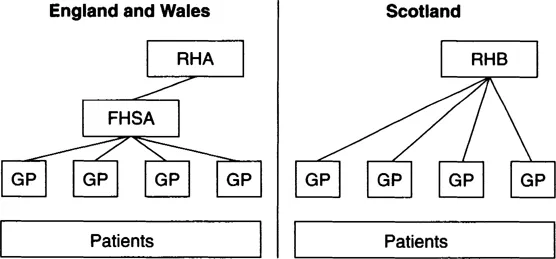

The administrative structure was also changed with the old style Family Practitioner Committees being replaced in England and Wales by FHSAs. These new bodies were given the ambiguous role of assisting doctors in the provision of primary healthcare whilst at the same time acting as quality monitors policing the new performance targets on behalf of the Government. In Scotland, the regional health boards (RHBs) remained responsible for the provision of family health alongside the hospital sector (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The role of FHSAs in England and Wales.

The situation was further complicated by the legislation which allows for the establishment of general practices with independent budgets for the purchase of external services, i.e. hospital beds for their patients. These doctors are known as ‘fundholders’. On the supply side of the NHS marketplace, by 1994, most hospitals and other service providers in England and Wales had become trusts. These trusts are independent of the health authority and can supply services to almost anyone with a budget.

Under the new contractual arrangements, it is possible for doctors to assume control of their own budgets rather than remain under the budgetary control of the local FHSA.

One of the problems in trying to carry out this study is the diversity found in general practice. There is no typical model of delivering primary healthcare.

Within a medium size town of 100000 inhabitants, one would expect to find about 60 family doctors with an average number of patients of 1670 per doctor. In such a town, one would expect to find a few large health centres where a complete service is offered including other health professionals such as practice nurses, therapists, opthalmists and even dentists. These would function alongside doctors working alone or in small units of two or three. Whereas during the 1960s and 1970s the trend was towards larger group practices, now there appears to be no discernible overall trend.

Certain factors, for example culture, do encourage particular modes of delivery. Single-practice doctors are prevalent in areas with a high proportion of the population from ethnic minorities.

The motivation for computerisation

The computerisation of general practice has been driven by the demands of Government legislation, specifically the 1987 White Paper, mentioned above and the introduction of new contracts and working conditions for GPs in 1990.

The emphasis on preventive care made specific demands for GPs to be able to identify groups of patients by age and sex as well as by clinical conditions. The obligation to provide an annual report further required the collection of data on referrals and on the use of external services.

A combination of ‘carrot and stick’ has led to a considerable increase in the uptake of technology. The doctors’ incomes were tied to performance targets such as the percentage of children immunised, or the percentage of women screened for cervical cancer. The need to carry out these tasks and monitor performance dramatically increased the doctors’ information requirements. This made the adoption of computers essential in the medium term and highly desirable in the immediate term. This formed the stick. The carrot offered was a 50% reimbursement of running expenses under the new contract.

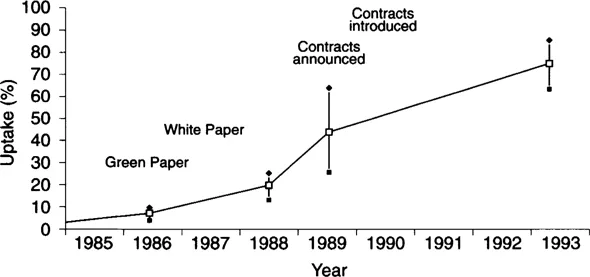

The best national statistics available (Department of Health, Statistics and Management Information Division, 1989, 1990, 1993) show that this approach was highly effective in increasing the use of technology. In 1989, prior to the new contracts, 25% of doctors had installed computer-based information systems. Just one year later, in 1990, after the new contracts were introduced, this figure had doubled to 50%. The comparable figure in 1993 had risen to 79%.

Other surveys indicate a similar trend, but show discrepancies between studies due to regional variations.

Even within health regions there are great differences. For example in the North West of England, in the Lancashire FHSA area, the uptake of computers on the Fylde Coast, where healthcare is provided generally from group practices working from large health centres, is almost universal. In Blackburn where the stereotypical practice is single-handed and working in poor neighbourhoods with a large population from ethnic minorities, computer uptake is low and reliable data are difficult to establish.

In spite of some discrepancies in the figures there are two discernible features. The trend is inexorably upwards and there was an acceleration when the new contracts were announced in 1989 (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 The installation of computer systems within general practice.

As an example, Salford FHSA, serving a generally poor catchment area which often corresponds to a slower uptake of computers, set 1994 as the target for 100% computerisation whereas other FHSAs had already reached this state.

Hayes (1985) identified the following barriers to the adoption of computers before the new contracts:

- • incomplete coverage of all activities

- • fears about confidentiality

- • high average age of GPs (>60% over 40).

These may be compared to barriers found by a survey of GPs using computers after the imposition of new contracts (Shum, 1992):

- • 66% of respondents found selecting systems to be a problem

- • 49% had experienced difficulty using their systems

- • 70% wanted to learn more but did not have time.

Shum (1992) described the then state of computerisation as the ‘end of the beginning’. In the rest of this paper, we shall seek to describe insights that have been gained from the experience and the lessons that can be learned.

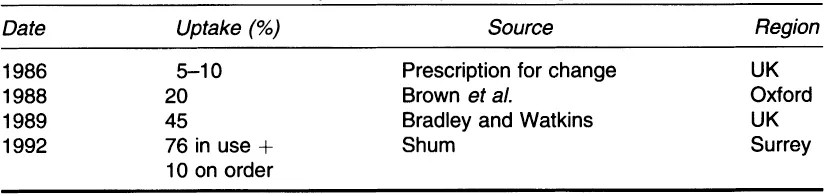

Table 1.1 Uptake of computers amongst GPs

Computerisation driven by Government legislation

The ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- About this book

- Dedication

- 1 Historical evolution

- 2 Primary care information systems

- 3 Coding

- 4 Information for health 1: the electronic health record

- 5 Information for health 2: PCOs

- 6 Information for health 3: patient information

- 7 Information for health 4: on-line resources

- 8 Information strategy for PCOs: the GPIMM model

- 9 Quality assurance

- 10 Introduction to clinical governance

- 11 The impact of scandal on clinical governance

- 12 Decision making in healthcare

- 13 Development of evidence-based practice

- 14 The context of evidence-based practice in the NHS

- 15 Systematic review and meta-analysis

- 16 National Service Frameworks

- 17 Technological support for evidence-based practice

- 18 Evidence-based practice within clinical governance

- 19 NHS Direct: decision support in action

- References

- Index