![]()

CHAPTER 1

An introduction to medical leadership and a perspective on this text

’Clinicians are expected to offer leadership and, where they have the appropriate skills, take senior leadership and management posts in research, education and service delivery. Formal leadership positions will be at a variety of levels from within the clinical team, to service lines, to departments, to organisations and ultimately the whole NHS. It requires a new obligation to step up, work with other leaders, both clinical and managerial, and change the system where this would benefit patients’ (Darzi, 2008).

The motivation for this book on medical leadership was partially triggered by Lord Darzi’s review of the health system culminating in the publication of High Quality Care for All in 2008. Policy analysts in the future may well see his strong messages about the importance of getting clinicians, and particularly doctors, more engaged in leading service improvements as a defining moment in the way in which health services in the United Kingdom are organised and led.

As the book was being finalised the new coalition government in the UK was consulting on its reform agenda for the NHS (England). Whilst much of the detail had yet to be resolved, it is very clear that the movement towards medical engagement and leadership promulgated latterly by Lord Darzi and others was to be strongly reinforced particularly through the emerging GP commissioning consortia.

The aim of this chapter is to introduce the topic of medical leadership and also to offer an overview of the key issues that are explored in more depth in subsequent chapters.

This movement did not start with the strong emphasis given to medical leadership by the Darzi Report. Doctors have been involved in the running of health services, locally, nationally and internationally, since the pioneers who initiated and organised health services many centuries ago. What is new is the emerging evidence of the relationship between the extent to which doctors are engaged in the planning, prioritization and shaping of services and the wider performance of the organisation.

We should at the outset stress that this is a book about medical leadership and engagement. Too often, commentators use the term ’clinical leadership’ when clearly meaning ’medical leadership’. We make no apology for focusing on doctors; other texts usefully cover the role the wider range of clinical professionals play in health systems. Much of the content of policy directions and statements prefer to use the term ’clinical leadership’ when all the subsequent text is focused on doctors. The evidence is that major changes to the way in which healthcare is delivered are driven by doctors. They are, de facto, the major decision-makers regarding the use of resources. This is not to detract from the key role other clinical professionals and non-clinical managers and leaders play. Delivery of healthcare is a team activity with all members having a major contribution to make to improve health and the way in which services are delivered.

Much of what we have to say about doctors being more involved in management, leadership and transformation can be applied to other clinical professions, but this is not the remit of this particular book. Medical leadership is a particular focus within the NHS currently and, we anticipate, for the foreseeable future.

At the time of publication, less than 5% of chief executives in the NHS are from medical backgrounds. Whilst there are some senior policymakers who seek to increase this, we don’t subscribe to this view per se. There is no evidence thus far that concludes medical chief executives are more effective than non-medical leaders. However, as Chapter 7 describes, there is evidence of the links between medical engagement and performance. Chapter 8 outlines how doctors in the future will be required to attain an agreed set of management and leadership competences at all levels of their training and careers. Our contention is that, as more doctors recognise their responsibility to the wider system of care and not just individual patients, more will want to assume leadership roles at all levels, including potentially as chief executives.

The set of leadership competences for doctors embodied in the joint NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Medical Leadership Competency Framework can equally apply to all clinical professionals. This view is now being reviewed by the NHS National Leadership Council and likely to be accepted by all clinical professional bodies.

To better understand the current strategies around medical leadership and engagement it is important to have an appreciation of the ways in which doctors have been involved in management, leadership and transformation of services. We suggest that the journey can be summarised as a movement from major domination preceding the setting-up of the NHS in 1948 through a period of disenfranchisement thereafter until perhaps the reorganisation of the health service in 1974. We contend that by this time some doctors, generally reluctantly, accepted representative roles. The Cogwheel Reports between 1967 and 1974 have had a significant impact on the way in which hospital services have been organised, i.e. around specialties ever since. The Reports also started the process whereby doctors initially took on representative roles for their specialty Cogwheel Division to and then to assuming executive responsibility for their specialty business unit and the concept of Service Line Management increasingly being introduced in Foundation NHS Trusts in England.

This shift from representation to accountability was reinforced by the Griffiths Report published in 1983 and further endorsed by the Resource Management Initiative in 1986 and the establishment of Clinical Directorates. The Griffiths view back in the early 1980s has continued to be stressed by Darzi and many other initiatives as outlined in more detail in Chapter 5. Put simply, Griffiths could not see how a service, department or organisation could be managed effectively unless it was managed by those who commit resources.

We also explore how the profession itself has changed over the same period as the policy and organisational arrangements have moved on. Whereas management and leadership were frequently dismissed by doctors and medical leaders in derogatory terms in previous eras, the medical profession is now very positively espousing the importance of doctors assuming leadership roles at all levels of training and careers and stressing their inclusion in the definition of a good doctor.

We explore in more detail why many of the initiatives introduced over the past 60 years have perhaps only been partially successful. We suggest that both managers and doctors represent two very powerful groups. Unlike many other countries, the United Kingdom has experienced a very strong managerialist culture, particularly over the past 25 years, which has often led to major conflict between clinicians and managers.

Trying to achieve some congruence between the individualistic nature of clinical practice and professionalism and the managers’ broader population and organisational perspective is an inevitable area of potential conflict and tension. The exercise of clinical autonomy is a crucial part of the application of knowledge acquired by doctors through their medical training. As Oni (1995) suggests, at worst some doctors will view managers as ’agents of government to control the expert power of the professional’.

The doctor:manager conflict is perhaps a stereotyped portrayal often reinforced by media coverage, including television dramas that delight in exaggerating the gap between the clinicians’ desire to provide the highest quality and quantity of care unfettered by resource constraints against the managers’ need to control expenditure within allocated budgets. This latter demand has been accentuated in recent years by the increased pressure on managers to meet government performance targets particularly over access and waiting time. It is perhaps this ’battle-zone’ of the performance management philosophy inherent in the concept of managerialism that creates the real challenge for health leaders. Seeking to get some shared and balanced understandings between the individual doctor’s desire to deliver high quality care to every patient and the managers’ need to deliver political and organisational imperatives has been a long-standing challenge. As we explore in later chapters, the more this potential chasm can be minimised the more likely local communities will benefit from high quality and efficient services. It is not an impossible dream, but understanding the different motivations and perspectives is perhaps the critical issue. Various reports into where this chasm has led to disastrous implications for patients have consistently confirmed this dysfunctionality. There can be no greater argument or incentive for seeking to reduce the divide.

It is as Barnett et al. (2004) contend: there is a need for a ’convergence of cultures’ and not a contest between any perceived or real emphasised differences. Finding common ground is the challenge. Who could deny that this is around service improvement and patient safety? Throughout this book we shall keep coming back to this need to find alignment of values and aspirations.

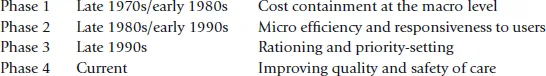

In Chapter 4 we describe the recent trends in healthcare reform and their implications for medical leadership. All too frequently health reforms leave us with a reality gap, i.e. the difference between the stated desired outcomes and improvements of reform and the reality. We postulate there have been four major phases of health reform in the NHS since the late 1970s, i.e.:

Whilst these four phases broadly apply to all four home countries, the approach to implementation and the governance arrangements to support the initiatives have differed particularly since the introduction of devolved governments at the end of the 20th century.

We widen the analysis of reforms and draw on other European and international studies which confirm that the gap between rhetoric and reality is not peculiar to the NHS. Whilst one diagnosis is around weaknesses in policy design, we also explore the power of clinical professionals and particularly doctors to frustrate the intentions of the policy-makers.

Reflecting on the various NHS reforms of the past 30 years or so, it is evident that all have recognised the importance of involving doctors in the reforms, but it is perhaps only the recent Darzi Report that sees clinical engagement and leadership as central to health reform. Even more recently, Liberating the NHS (2010) has seen general practitioners move to centre stage in England through their central role in commissioning services.

We explore some of the factors that hinder the active engagement of doctors in leading health reforms and suggest that both policymakers and those implementing these need to understand what Henry Mintzberg described as ’professional bureaucracies’ (Mintzberg, 1979). Perhaps the current drive for greater engagement of doctors in leading reforms both nationally and locally suggests that there is a better explicit understanding of this concept by both policymakers and the medical profession.

Throughout the book we provide examples of how high performing organisations are typified by strong partnerships between doctors and managers at all levels. Distributed or shared leadership is gaining prominence within new leadership paradigms of, for example, microsystems and service line management approaches.

We reflect that, whilst healthcare reform since the 1970s has highlighted the need to engage doctors more effectively in reforms, it is only perhaps over the past couple of years that there is a shared appreciation by policymakers, the medical profession and NHS leaders that the rhetoric reality gap can only be closed by a genuine commitment to greater medical engagement and leadership.

The evidence for the greater engagement of doctors is perhaps best summarised in Chapter 7 where we explore some of the inter-related concepts of performance, leadership and engagement. We draw on some of the growing body of evidence suggesting that good management practice and effective leadership can have a positive impact on organisational performance.

The authors have been involved in a major national study looking at the relationship between medical engagement and organisational performance. Much of the limited work around the impact of clinical engagement has hitherto tended to describe different models and approaches within specific organisations that appear to have led to a range of defined benefits, e.g. greater staff satisfaction and commitment, reduced staff turnover, greater patient satisfaction, etc.

In Chapter 7 we outline how an existing Professional Engagement Scale was adapted and tested to provide a discrete medical engagement focus. The Medical Engagement Scale (MES) is based around three meta levels:

Meta Scale 1 | Working in an open culture |

Meta Scale 2 | Having purpose and direction |

Meta Scale 3 | Feeling valued and empowered |

A detailed analysis of the comparison between the MES Index and overall Healthcare Commission (now Care Quality Commission) ratings is provided in Chapter 7, but it is apparent that organisations scoring more highly on engagement are independently assessed as superior in performance across a number of areas. In addition, more detailed statistical analyses reveal a large number of significant relationships between the medical engagement index and other independently collected performance markers, e.g. standardised mortality rates and the National Patient Safety Agency data on incidents resulting in severe harm.

The evidence from this study provides confirmatory support for the policy reform agenda based around more doctors leading improvements in quality, safety and productivity. It also supports the notion that shared and distributed leadership at all levels is more likely to produce the benefits sought. Many local studies have demonstrated the impact of effective medical engagement, but the medical engagement scale appears to offer a powerful and validated tool for organisations to benchmark themselves against other hospitals and primary care trusts and to identify areas for improvement. Lessons from those Trusts with high levels of engagement should also be useful for the new GP Commissioning Consortia as they are established.

We also draw on a study examining the ways in which doctors are involved in medical leadership in a number of countries and how they were prepared for leadership roles. Edwards, Kornacki and Silversin (2002) contend that there has been a breakdown in the implicit deal between doctors, patients, employers and society around what the parties to the relationship give and what they get in return. They describe the changing societal context within which doctors now practise, including greater accountability for their performance, need to deliver patient-centred care and to work collectively with other clinicians and st...