eBook - ePub

Operative Obstetrics, 4E

- 551 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The new edition of this authoritative review of the clinical approach to diagnostic and therapeutic obstetric, maternal-fetal and perinatal procedures will be welcomed by all professionals involved in childbirth as a significant contribution to the practice of maternal-fetal medicine and surgical obstetrics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall, uterus, and pelvic organs

CONTENTS

Anterior abdominal wall

Boundaries and surface landmarks

Skin and subcutaneous tissue

Muscles and rectus sheath

Transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal tissue, and peritoneum

Abdominal surgical incisions

Uterus

Parts and relations of the nongravid uterus

Size and positional changes of the gravid uterus

First trimester

Second and third trimesters

The myometrium during pregnancy

The cervix of the gravid uterus

Changes in the uterine cavity during pregnancy

Fallopian tube

Ovary

Ligaments of the uterus

Uterine blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves

Arteries

Veins

Lymphatics

Nerves

Pelvic portion of ureter

Bladder and urethra

Bladder

Urethra

Sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal

Sigmoid colon

Rectum

Anal canal

Obesity in pregnancy

Acknowledgment

References

A complete and thorough knowledge of female abdominal and pelvic anatomy is important for specialists in obstetrics and gynecology since patient safety in the operating room during surgery is critically dependent on this knowledge along with the appropriate functioning of the operating room team.1 Therefore, this chapter reviews anatomy of the female pelvis with emphasis on avoiding anatomic complications of laparotomy and/or laparoscopic and robotic pelvic surgery2 and on structures important in pelvic organ support and urinary continence.3,4

ANTERIOR ABDOMINAL WALL

Boundaries and surface landmarks

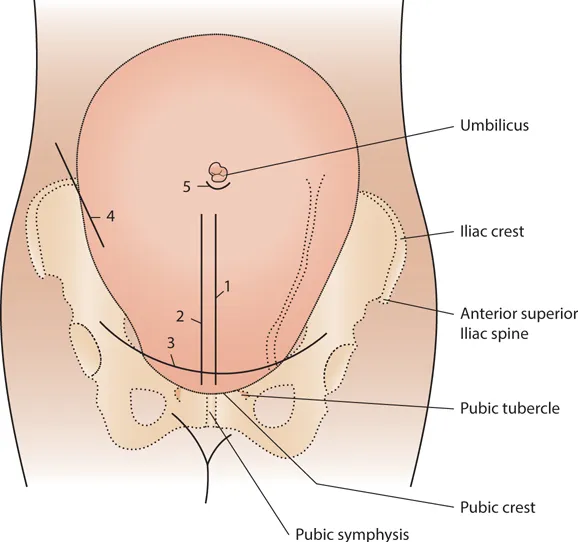

The anterior abdominal wall is bound above by the xiphisternal junction in the midline and the arching margin of the lower costal cartilages (costal margin) laterally. Below, it is bound by the symphysis pubis in the midline and laterally by the pubic crest, inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament, and iliac crest (Figure 1.1). There are no bony structures laterally, the wall being limited by a vertical line from the middle of the axillary depression (midaxillary line) that crosses the 10th rib to the iliac crest. Additional bony landmarks are the xiphoid process in the midline above, the pubic tubercle located below at the lateral end of the pubic crest, and the anterior superior iliac spine at the anterior end of the iliac crest. The inguinal ligament courses from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine, separating the abdominal wall from the thigh. The pubic bone and symphysis pubis separate the wall from the genitalia.

Figure 1.1 Surface landmarks and the sites of popular incisions for obstetric surgery: (1) vertical median incision, (2) vertical paramedian incision, (3) transverse incision, (4) oblique incision, and (5) umbilical incision.

In addition to the above bony landmarks, several soft tissue landmarks are apparent, their degree of visibility largely dependent upon the amount of fat in the subcutaneous tissue. Most obvious is the umbilicus, which lies in the midline about two-thirds of the distance between the suprasternal (jugular) notch and the symphysis pubis5 at approximately the level of the lumbar (L3–4) intervertebral disk. The aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal muscles unite in the midline with their equivalent on the other side, forming the linea alba, which runs from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis. The linea alba is usually the strongest point in the aponeurotic part of the wall. In lean, muscular subjects, it is represented on the surface as a vertical midline depression. On each side the lateral margin of the rectus muscle is evident in similar subjects, appearing as a slightly curved, vertical depression called the linea semilunaris.

The surface markings and contour of the anterior abdominal wall vary considerably with age, body mass index (BMI), muscular status, parity, and period of gestation. The normal landmarks mentioned above usually are present during pregnancy, and, in some instances, the umbilicus and linea alba may be more intensified because of the distention of the wall by the expanding uterus. Abdominal contents sometimes protrude through a weak umbilicus, resulting in an umbilical hernia. The distention during pregnancy also may widen the linea alba, thereby separating the rectus muscles and creating diastasis recti of varying degrees. In severe cases, the uterus is covered only by skin, a thin layer of fascia, and peritoneum. A brown-black pigment frequently is deposited in the midline skin, forming the linea nigra.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue

Usually the skin of the abdomen is smooth, very elastic, and firmly attached to the deeper tissue in the midline. The cleavage lines of the skin (Langer’s lines) mainly run transversely.6 Transverse incisions through the skin course mainly parallel to the lines of tension, whereas vertical incisions cut perpendicular to them. The cutaneous lips of vertical incisions, therefore, tend to retract. In the latter months of pregnancy about one-half of all pregnant women develop reddish, slightly depressed streaks (striae gravidarum) in the abdominal skin. In addition to reddish striae, the abdominal skin of multiparous women frequently exhibits glistening, silvery, vertical lines that represent cicatrices of previous striae.

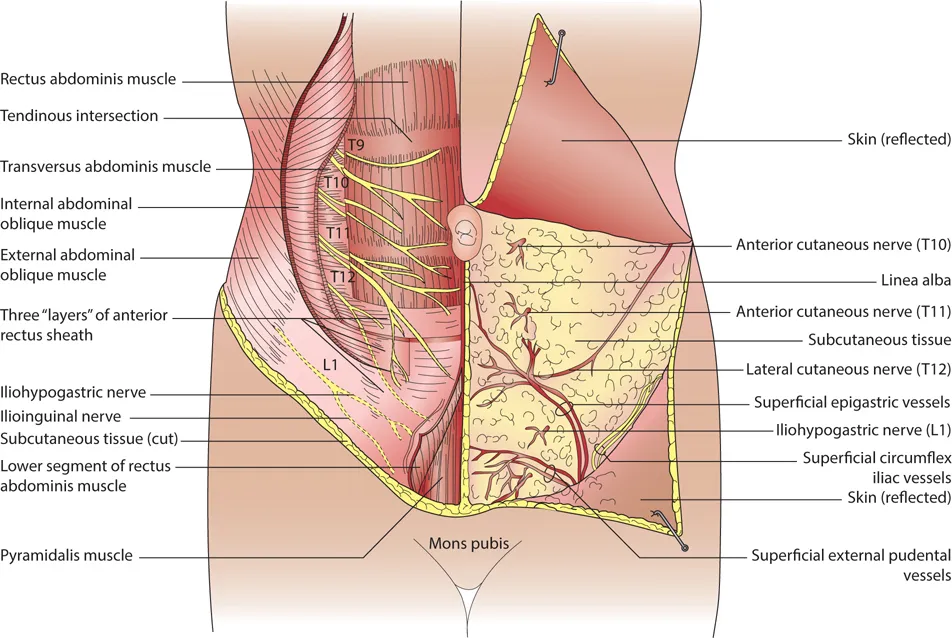

The subcutaneous tissue (superficial fascia) of the anterior abdominal wall, like other areas of the body, is composed mainly of fat and connective tissue and contains cutaneous blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves (Figure 1.2). The quantity of fat in this region varies remarkably from one individual to another. In fatty subjects, the outer portion of the superficial fascia in the lower abdominal wall appears more fatty in texture than the deeper portions, where sheets (lamellae) of overlapping fibrous connective tissue tend to concentrate.7 The fibrous sheets do not always form on the deep surface of the fat. Often they are enclosed in fat themselves and, on occasion, may comprise more than one layer.8,9 In thin individuals, it may be impossible to demonstrate distinct fatty and fibrous portions. The subcutaneous tissue is continuous inferiorly into the labia majora and perineum. Often a vertical, thickened, fibrous band is present in the midline in the lower abdominal wall which is adherent to the linea alba. It represents the fundiform ligament, which usually is described only in the male. On each side of the midline the subcutaneous layer is loosely separated from the deep fascia over the lower part of the external abdominal aponeurosis. This fascial cleft is quite definite and is continuous below with a similar cleft in the perineum.

Figure 1.2 Front view of the layers and components of the infraumbilical part of the anterior abdominal wall. The more superficial subcutaneous layer is exposed on the left side of the body; the deeper muscular layer and the anterior rectus sheath are shown on the right side.

The superficial (subcutaneous) arteries arise from various sources and freely anastomose with each other in the subcutaneous layer. Most of the skin below the umbilicus is supplied by three small branches that ascend from the femoral artery passing superficial to the inguinal ligament: the superficial epigastric courses obliquely toward the umbilicus and then rises upwards approximately 4 cm lateral to the midline, the superficial circumflex iliac passes laterally just above the iliac crest, and the superficial external pudendal runs medially, superficial to the round ligament of the uterus to the perineum and lower-most part of the wall (Figure 1.2). The superficial (subcutaneous) veins accompany the arteries but are more numerous and form extensive anastomoses. Below the umbilicus they course mainly downward, also crossing superficial to the inguinal ligament to empty into the great saphenous vein in the upper thigh. The subcutaneous veins in the lower abdominal wall anastomose with those draining the upper wall. When the deeper, main venous drainage of the lower limb is obstructed, these anastomoses enlarge, forming a large venous channel, the thoracoepigastric vein that connects the great saphenous vein with the axillary vein. The superficial (subcutaneous) lymph vessels generally follow the course of the veins. Below the umbilicus they course downward to the superficial inguinal nodes located just below the inguinal ligament. The cutaneous nerves arise from the lower six thoracic nerves and the first lumbar nerve (T7–12 and L1). The seventh thoracic nerve supplies the skin over the xiphoid process, the tenth thoracic nerve courses to the umbilicus, and the eleventh and twelfth thoracic nerves and the iliohypogastric nerve (L1) innervate the skin of the infraumbilical portion of the wall. The nerves to the skin on each side of the midline are arranged in two vertical rows, a small, anterior, cutaneous series that pierce the anterior rectus sheath a short distance from the midline, and a larger, lateral, cutaneous series that enter the subcutaneous layer near the midaxillary line. The anterior branches of the lateral cutaneous series supply a large segment of the anterior wall.

Muscles and rectus sheath

The anterior abdominal wall contains five pairs of muscles that support and protect the abdominal viscera in front and laterally (Figure 1.2). The muscles are mainly attached above and laterally to the sternum and lower ribs, and below to the pelvic bone. Three of the muscles are located laterally and superimpose as sheets one on the other. From superficial to deep, they are the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus muscles. The rectus and pyramidalis muscles make up the medial group lying adjacent to the linea alba and enclosed in varying degrees by the rectus sheath. The rectus sheath is formed by the fusion of the sheet-like tendons (aponeuroses) of the three lateral muscles as they course to the midline. The linea alba might be considered the common area of decussation of the aponeuroses of the three lateral muscles rather than their insertion.10

The external oblique muscle originates from the outer surface of the lower eight ribs, its fibers coursing downward and forward. The more posterior fibers insert directly on the outer lip of the iliac crest. The remaining muscle fibers give rise to a broad aponeurosis that passes in front of the rectus muscle to attach to the linea alba. Above, the aponeurosis attaches to the sternum; below, it attaches to the anterior superior iliac spine, pubic tubercle, and symphysis pubis. The lower border of the aponeurosis is thickened and folded back on itself to form the inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The inguinal ligament is bound down to the deep fascia of the thigh (fascia lata). A small oval opening in the external oblique aponeurosis, the superficial inguinal ring, is located about 2.5 cm above and lateral to the pubic tubercle. Its inferior margin lies close to the inguinal ligament. The round ligament of the uterus passes through the ring into the labium majus, where it attaches to the subcutaneous tissue.

Immediately deep to the external oblique is the internal oblique muscle. Its fibers arise from the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, iliac crest, and lumbodorsal fascia. The posterior fibers run upward and forward to insert into the lower ribs and their cartilages. The anterior fibers course medially and give rise to an aponeurosis. Most of the fibers of the external and internal oblique muscles run at right angl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall, uterus, and pelvic organs

- 2 Topographic anatomy of the perineum, vulva, vagina, and surrounding structures

- 3 Clinical pelvimetry

- 4 First-trimester embryofetoscopy

- 5 Chorionic villus sampling

- 6 Amniocentesis

- 7 Fetal transfusion

- 8 Fetal reduction and selective termination

- 9 Spontaneous and indicated abortions

- 10 Percutaneous intrauterine fetal shunting

- 11 Cordocentesis

- 12 Minimally invasive fetal surgery—The Colorado approach

- 13 Fetal surgery—The Texas Children’s Fetal Center approach

- 14 Cervical insufficiency

- 15 Advanced extrauterine pregnancy

- 16 The role of cesarean delivery in the management of fetal malformations

- 17 Evaluation and management of stillbirth

- 18 Antepartum hemorrhage

- 19 Intrapartum fetal monitoring

- 20 Normal vaginal delivery

- 21 Shoulder dystocia

- 22 Postpartum hemorrhage

- 23 Forceps delivery

- 24 Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery

- 25 Fetal malpresentations

- 26 Delivery of twins and higher-order multiples

- 27 Maternal birth injuries

- 28 Puerperal inversion of the uterus

- 29 Wound healing, sutures, knots, needles, drains, and instruments

- 30 Cesarean delivery

- 31 Prevention of surgical site infections

- 32 Cesarean scar pregnancy

- 33 Anesthetic procedures in obstetrics

- 34 Cardiac monitoring in pregnancy

- 35 Trauma in pregnancy

- 36 Surgery during pregnancy

- 37 Urologic complications during pregnancy

- 38 Management of malignant and premalignant lesions of the female genital tract during pregnancy

- 39 Gestational trophoblastic disease

- 40 Patient safety

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Operative Obstetrics, 4E by Joseph J. Apuzzio, Anthony M. Vintzileos, Vincenzo Berghella, Jesus R. Alvarez-Perez, Joseph J. Apuzzio,Anthony M. Vintzileos,Vincenzo Berghella,Jesus R. Alvarez-Perez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gynecology, Obstetrics & Midwifery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.