eBook - ePub

Winning the Publications Game

The smart way to write your paper and get it published, Fourth Edition

This is a test

- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Winning the Publications Game

The smart way to write your paper and get it published, Fourth Edition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The publications game can seem tricky: knowing where to start, how to plan and draft a paper, who to pitch it to and how to present it can appear difficult enough. With the advent of e-publishing and ever-tougher regulatory frameworks surrounding research, the picture can seem even more intimidating.

In this classic guide, Tim Albert demystifies the process of getting research published in his characteristically clear and engaging style. From the initial brief to final manuscript and beyond, all is explained in jargon-free, no-nonsense and encouraging terms, providing indispensable guidance to clinicians, scientists and academics in giving their research the platform it deserves.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Winning the Publications Game by Tim Albert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Know the game

‘Writing is really fun once you realise it is a big marketing game.’

The process of writing

The purpose of this book is to enable you to write, and then to have published, a scientific paper or article in a peer-reviewed journal – in other words to have your name on the established databases. It is not a book about how to ‘do science’, but a book on how to translate the science you do into publishable papers.

The driving force has come from what I have seen over more than two decades, while giving courses on effective writing to doctors and other scientists. What struck me was that:

1. many of them felt that they would be failures unless they became published authors

2. few of them had actually been given practical advice on how to become published authors.

Conspiracy theorists would have a field day. They would argue that those who have discovered the secret of publication are, for obvious reasons, unwilling to pass it onto younger rivals. That is clearly untrue. There is no shortage of senior scientists willing to devote much time to helping junior colleagues, and there are dozens of worthy books explaining in great detail the criteria for acceptable scientific articles.

Yet somehow all this energy achieves little, and many people who want to write remain confused and unable to start. To some extent this is a particular characteristic of science writing, which has become highly specialised and removed from other types of writing. Many ‘experts’ discuss in great detail exactly what conditions a ‘good’ article should fulfil; but few promote, or even seem aware of, some of the useful techniques for how to get started and write it.

However, there is a wealth of information on the process of writing, which is readily accessible to those who go outside the world of science into the world of professional communicators. That is the gap this book tries to fill, by treating writing tasks, quite simply, as writing tasks, and by applying the (mainstream) techniques and tricks of the professional writer to the (specialist) world of scientific writing. This may be considered radical, and some of the ideas may give offence. But I believe strongly that there are basic principles of effective writing that can be applied to all types of writing. It can work. As one participant once wrote to me: ‘Before your course I’d had an article rejected by the BMJ. After the course I rewrote it and it was accepted by The Lancet.’

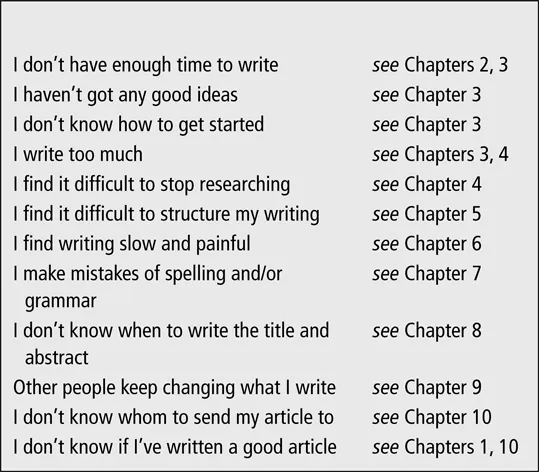

This book divides the process of writing into 10 easy steps. Some of the main problems that this book addresses, and the chapters where their resolution may be found, are given in Figure 1.1. What I hope shines through is that, despite the inevitable episodes of pain (such as these opening seven paragraphs which took more than 20 drafts), writing should be fun. It should also be rewarding and even liberating. This is not an impossible dream: it depends more than anything else on the writer’s frame of mind, and therefore should be easy to fix.

If that sounds like one of those motivational books, so be it. That is precisely what I hope this book will be.

FIGURE 1.1 Common problems faced by writers

The scientific article as truth

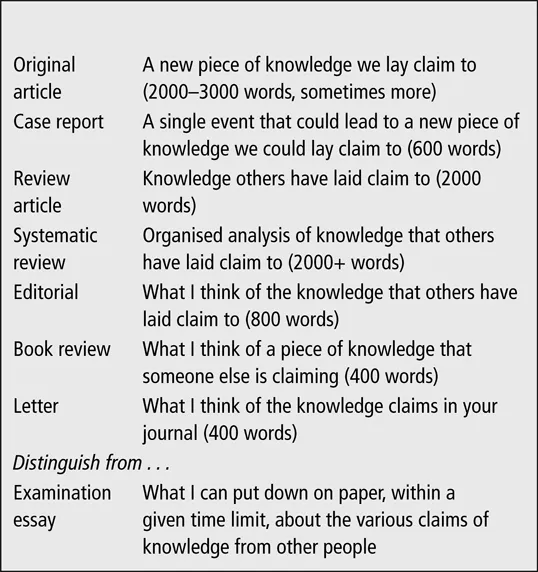

There are many different types of scientific writing (see Figure 1.2), but this book focuses on how to write an original scientific ‘article’, or ‘paper’ (the terms seem interchangeable). I have chosen to focus on them because they have become the main currency of scientific writing. They have also adopted a particular format, and on the face of it seem least likely to share common ground with other types of writing. In fact I believe the reverse is true: there are principles of effective writing that you can use to master scientific articles, and that you can also use for all other types of writing, including reports, letters, memos, grant submissions and patient information. This book will apply those principles.

FIGURE 1.2 Different types of scientific writing

Scientific articles have a long history. The first reviewed paper is generally considered to date from the middle of the 17th century, and a series of developments since (see Figure 1.3) has led to a process that is complex, sophisticated and international. The basic form of a scientific article consists of a 2000- to 3000-word report that normally addresses a single research question. It uses a standard structure of Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion (the ‘IMRAD’ structure, of which more later), plus other specific items, such as title, abstract and list of references. These articles are written in a particularly stylised form of English.

FIGURE 1.3 Some key dates in the evolution of scientific publishing

One or several authors submit an article to the editor of a journal. The editors have knowledge and integrity, according to the conventional view, and act as gatekeepers, selecting the ‘good’ and rejecting the ‘bad’. They are assisted by a complex system of peer review, under which other people working in the same field are invited to give their opinion.

The criteria on which papers are accepted are generally considered to include the following:

• original: is the work new?

• significant: does it represent an important advance?

• first disclosure: has it appeared in print elsewhere?

• reproducible: can the work be repeated?

• ethical: has it met the agreed standards?

Each week thousands of these papers appear, in publications ranging from international general journals, sometimes run by multinational publishing groups, to small specialist journals published by a group of doctors in one country and who share a common professional interest. Most of these papers are now available on international databases, thus ensuring that, within a short period of completing the work, the findings are available throughout the world. Most of the journals are now publishing electronically.

The system is impressive. Week by week our knowledge grows as original articles – the basic building blocks of science – are approved, published and disseminated. It’s a powerful thought and a comforting view.

The truth about scientific articles

It also happens to be a naive and unduly rosy view. Dr Stephen Lock, former editor of the BMJ, has written: ‘The journals are serving the community poorly. Many articles are neither read nor cited; indeed many articles are poor. In general, medical journals seem to be of little practical help to clinicians facing problems at the bedside … Scientific articles have been hijacked away from their primary role of communicating scientific discovery to one of demonstrating academic activity. No more are grant-giving bodies basing awards on the quality of scientific research; the emphasis has switched to quantity.’1

The performance of journals does not always live up to the glowing picture painted of them. One major problem is that the peer-review system, for all its intricacies, does not guarantee that the bad will be weeded out or even that the good will be published in the most appropriate journal. There has been a small but steady stream of cases of authors copying data from a previously published article (plagiarism), publishing the same article twice (duplicate publication) or simply inventing data (fraud).

Nor do all the efforts of reviewing guarantee that papers will be good, as opposed to mediocre. The comments of others can be invaluable, but they can also have the effect of promoting conservatism and disparaging innovation. There is a danger that, by the time articles are passed for publication, they carry the stamp of agreement by committee and have lost any spark of originality. Most serious of all is the charge that the reviewers may provide unwitting bias on the one hand, and on the other downright chicanery (as one research team tries to discredit the results of a rival or use the information in a refereed paper to further its own research).

All this makes life extremely difficult as far as writers are concerned. Publication is not just a matter of adding to intellectual debate and seeing your name in print. Nowadays it is one of the main factors taken into account when assessing the worth – and funding – of individuals and research groups. This means that in recent years the pressure to publish is increasingly being replaced by pressure to publish in journals with high reputations.

Unfortunately, this can be extremely unfair, as illustrated by a story told by a young researcher on a course. She had written a paper which had been accepted for publication by a reputable journal. She scanned the journal for months – in vain. Eventually she telephoned the editorial staff. She was told that the article had been mislaid but, now that it had been found, it could not be published because the editor felt that the figures were now out of date. The author was heartbroken. In her eyes, she had fulfilled the criteria, but did not receive the kudos, or the points for her CV. At the same time the editor was well within his rights. If he felt that the readers would not be interested, it would have been wrong to have published it.

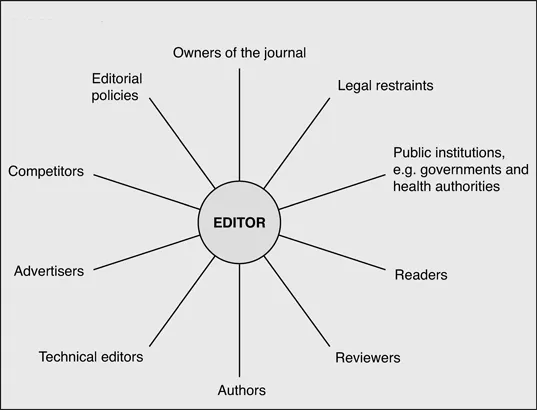

At heart is the harsh reality that our main method of validating science is ultimately based on a commercial system. Editors have many roles and have to reconcile many pressures (see Figure 1.4), but one of their main tasks is to ensure that the publication continues to exist. For this, articles must be read and cited. If this no longer happens, the journal will have to close. As Lawrence K Altman, a medical correspondent of The New York Times, has reminded us: ‘Scientific journals represent scholarship. But they are also an industry. Medical and surgical journals in North America collect more than $3 billion in advertising revenue each year.’2

The traditional idea – that a ‘good paper’ will automatically receive the recognition it deserves – is clearly unrealistic. But where does this leave the aspiring writer?

FIGURE 1.4 The range of pressures on an editor

Marketing: a vulgar but comforting approach

The way out of this mess is to stop thinking of scientific papers as a means of assessing individual worth, and more as part of a commercial publishing system. Journals need good articles and every editor’s ultimate nightmare is that there will not be enough copy to fill the journal. As a potential supplier, you have a marvellous opportunity: if you can provide the right product for the right market, you will achieve your sale – and be published.

This means redefining yourself as a supplier, your article as a product and your goal as convincing the customer (specifically: the editor) that he or she should ‘buy’ it. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword to the fourth edition

- Preface to the fourth edition

- About the author

- 1 Know the game

- 2 Know yourself

- 3 First set yourself a brief

- 4 Expand the brief

- 5 Make a plan, or four

- 6 Write the first draft

- 7 Rewrite your draft

- 8 Prepare the additional elements

- 9 Use internal reviewers

- 10 Send off the package

- References

- Some useful websites

- Index