1

Alzheimer’s disease: an introduction to the issues

Marcus Longley and Morton Warner

What is Alzheimer’s disease?

In 1907, a 51-year-old woman died in Germany after suffering from dementia. A post mortem examination was carried out, which revealed that her brain was highly abnormal when compared with non-demented women of the same age. In particular, the pathologist found it was shrunken in size, many of its cells had died and disappeared, while others contained ‘dense bundles of fibrils\ Throughout the brain, there were deposits of a ‘peculiar substance’. The pathologist’s name was Alois Alzheimer, and this was the first diagnosed case of a disease that now is known to affect 1 in 20 people over the age of 65 in Europe, with this rate doubling every five years between the ages of 65 and 95.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the commonest form of dementia, accounting for between one-half and two-thirds of all cases. Its causes are still largely unknown, although a variety of factors are probably involved, including age, genetic factors, other diseases, lifestyle, environment, head injuries, and even level of education. It knows no social boundaries, as the authorship of the Foreword shows, and brings about feelings of despair and compassion from all who come into contact with sufferers.

AD leads to a progressive decline in the ability to remember, to learn, to think and to reason, and sufferers have difficulty finding and using the right words, and in recognising people, places and objects. Ewart Myer, a 78-year-old carer, described the problem as follows:

A person with Alzheimer’s lives in a span of a few seconds. They cannot relish the past; they have nothing to look forward to; they live in a world of illogic.

Alice Zilonka, aged 73, had AD herself, and described her state even more succinctly:

My mind is like a dark thunderstorm.

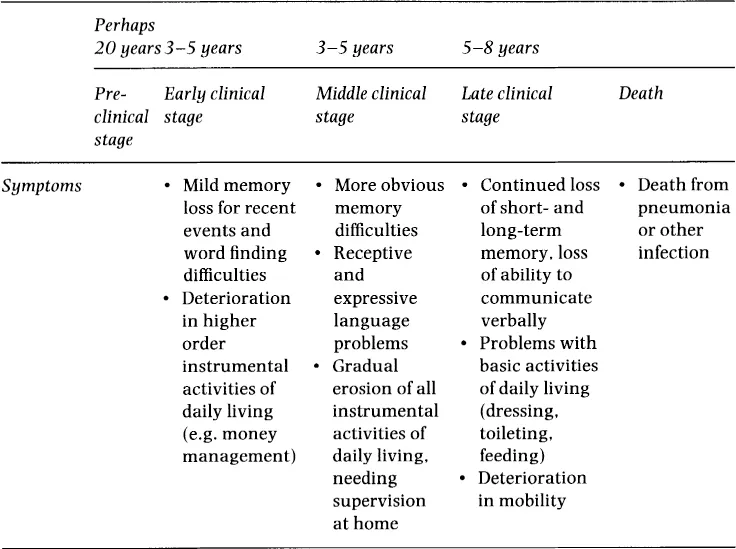

The disease progresses at different rates in different individuals, but a broad time-line of development has been established - see Table 1.1. The sufferer’s personality can change out of all recognition, often with a particular personality trait becoming grossly exaggerated. In its most advanced stages, the dementia results in almost total destruction of the brain’s ability to function, with the sufferer becoming more and more withdrawn, and almost unable to control their behaviour.

The onset of the condition is insidious, and early symptoms are often not recognised, being mistaken for general signs of ageing. Forgetfulness is perhaps the most common cause for alarm in relatives and friends. There is no easy test to establish whether someone has AD, short of a post mortem examination. The task of the doctor making the diagnosis in a living patient is made more difficult by the fact that the symptoms of early onset AD are similar to those of several other conditions - depression, vitamin deficiency and thyroid problems, for example. Diagnosis therefore usually involves a process of measuring the patient’s mental state, and then of eliminating the other possible causes of the symptoms.

Table 1.1: Time-line for development of AD

At present there is no cure for AD, and the symptomatic treatments are of limited benefit to most patients, especially in the middle and later stages of the disease. Help therefore tends to focus on maintaining an environment which places least stress on the sufferer, and most importantly offering whatever help is necessary for the carer. Once the diagnosis has been made, it is possible for the sufferer and their family to plan ahead and to anticipate - and therefore minimise - the future impact of the disease on all concerned. Support for carers takes a wide variety of forms, from providing information and advice, to practical help with basic caring tasks and respite from the constant burden of care.

Most carers are women, although a significant number of men are also caring for their spouses. The motivations and rewards of caring are often substantial, but so too is the burden, tinged as it often is with regret, depression, and feelings of loss as a carer’s loved one changes in front of them. The following descriptions, from a 39-year-old caring for her husband with AD, and from a daughter caring for her mother, are typical of many:

The silence is deafening and the loneliness shattering. I remember the times when my husband and I would sit down with the crossword, gossip over an evening out with friends and discuss simple things like our children and our retirement plans. I miss those aspects of our relationship more than I can say.

Mother was always the cheerful outgoing person in the family. We knew she was becoming forgetful but the worse thing is that she doesn’t want to do anything any more. She doesn’t do her hair, she doesn’t keep the house tidy, she absolutely won’t go out.

What makes AD different?

Every disease and disability poses challenges to the responsible professionals and policy-makers, and exacts high costs from those who suffer from it and their carers. AD, however, is different from most others, and therefore deserves special attention from policy-makers and professionals. Three key features of the disease are particularly relevant. First, there is the progressive nature of the condition. This makes early detection difficult, demands different levels of response from health and social care services as time goes by, and requires long-term commitment from carers. Secondly, there is no cure, and little effective treatment. This all too often encourages health and social care agencies and professionals to place too little priority on AD services, passing too much of the responsibility for care onto family members. This is compounded by paying too little attention to the needs of carers in service planning processes: two-thirds of dementia sufferers are cared for at home. Thirdly, the numbers of those with AD will increase significantly in the coming years, as the population ages.

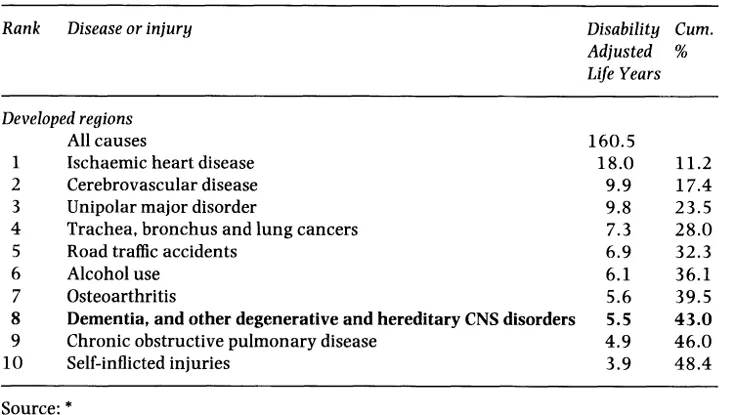

Table 1.2: Top ten leading causes of DALYs given in millions in 2020 (baseline scenario, both sexes)

In all, it is a major issue which will assume even greater importance in the future. Some significant work has been completed recently which quantifies the burden of disease likely to accrue in the early part of the next century.* Table 1.2 shows that AD, as one of the neuro-degenera-tive group, will feature highly.

Alzheimer’s disease - a paradox

Across Europe there is a fundamental paradox at the heart of our attitude as a society towards AD. On the one hand, there is general recognition that people with the condition (and other dementias) receive a generally poor level of service in comparison with other groups; and yet, on the other hand, there is little sign of any determined attempt to improve the situation. Such paradoxes are far from being unique in public policy. It is upon an understanding of the reasons for the paradox that future progress depends, and part of the answer lies in the low status accorded to this group of people.

Although the member states differ considerably in terms of their policies and services for people with AD and dementia generally, it remains the case that every state accords this client group relatively low status. There are many indicators of this, such as the absence of planning processes and policies specifically targeted at the group, the relatively low prestige enjoyed by many doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals working with demented patients, and the ambivalent nature -bordering on social stigma - typical of much popular media coverage of dementia, both factual and fictional. This low status underlies many of the other issues described in this book.

The causes of this low status are many and various. They include:

the often ambiguous attitude of society at large to its older members - a complex mixture of respect, love and sympathy, coupled with contempt, fear and lack of understanding

the ‘invisibility’ of the problem, in part a consequence of the marginalised position of most patients, effectively denied a public voice by the consequences of their condition

the willingness - at least hitherto - of most families of people with dementia to arrange for the care of the affected relative without demanding more resources

the lack of good models of service provision emerging from the past -partly because dementia has only relatively recently become a major public policy issue as the population has aged

the fact that there is no cure, which tends to conflict with the overriding medical (and other health professionals’) aim to save life

the concern of Ministries of Finance and insurance companies that the burgeoning numbers of demented people, coupled with the low level of historical provision for them, might lead to an explosion of demand for services which cannot easily be afforded.

Many of the above are, of course, interrelated.

To see how the paradox is sustained in practice, consider the position relating to the early diagnosis of dementia. The intellectual and humanitarian case for early identification of people with AD is well established. And yet, many policy-making organisations, as well as individual practitioners, still do not accept this; or if they do, seem unable or unwilling to bring it about. This is partly a consequence of the generally low status of AD. But there are also more specific causes. Many professionals lack the relevant skills or time to perform the differential diagnosis necessary, or can see little point in so doing, given the limited possibility of doing what they most want to do, i.e. preserve life. There may also be an argument that the patient’s best interests - in terms of preserving their dignity or confidentiality - are not best served by making an early diagnosis. Relatives, too, will often collude with professionals and request that the diagnosis not be disclosed to the patient, further underscoring family members’ negative attitudes to Alzheimer’s disease. In such a way, thousands of well-meaning people - professional and lay - sustain the paradox.

Inequity between member states of the EU

It is often difficult to compare the quality of healthcare provision across Europe, given the very different organisational and philosophical contexts in which the member states work. In the case of AD, however, such comparisons are made somewhat easier by the fact that there is such a high measure of agreement on the basic characteristics of good service provision and policy for AD. It is possible, therefore, to map the extent to which individual member states fall short of the ideal.

There are many examples of inequity of provision of dementia care within and across the different member states. Clinical practice models are quite advanced in some countries but are embryonic or at an early stage of development in others. Even in those where dementia care practice is well developed, there is often geographical inequity in the provision of such services, or imbalances in the level of specialist provision, that translate into inequity for the sufferers and their carers. In most member states, primary care personnel are significantly under-trained and under-resourced to deal with the rising tide of dementia sufferers, contributing to late detection and treatment.

Funding mechanisms, drug reimbursement procedures and prescribing for new drug treatments in AD vary from country to country and represent another source of inequity for patients and their carers. AD and dementia are almost unique among the leading causes of chronic disability and ill health in that the sufferers themselves are most often not able to act as advocates for the treatment of their condition. This may partly account for the low priority given in some member states to the funding of new treatments and interventions for this condition.

No state, then, has a perfect level of provision, and there is room for improvement in all. It is also true, however, that some have managed to develop better provision than others. This is often explained by such basic issues as the strength of the local economy (as a key determinant of the level of expenditure on welfare); but, whatever the cause, there is a clear prima facie need for co-ordination of services and policies to reduce current inequities.

‘Joining up’ services and policies

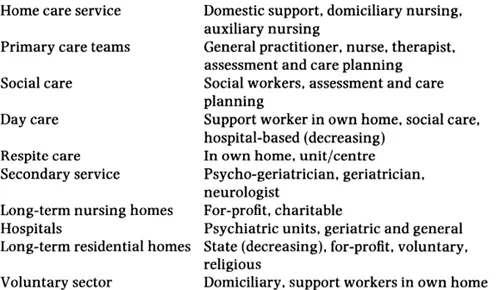

Alzheimer’s disease patients have a multiplicity of different, and often quite intractable, problems. There is much attention paid now to the need for multidisciplinary health and social care, and for the application of both medical and social models of care, and nowhere is this more needed than in the case of services for people with AD. A whole range of professional disciplines and skills must be brought to bear at the appropriate junctures. Box 1.1 itemises these.

Such multidisciplinary working, across many agencies, requires considerable co-ordination - the various elements need to be ‘joined up’ into a coherent whole, focused primarily on the needs of the clients.

It is not that multi-agency dementia services do not exist, but that policies frequently do not support their development or continuation, and other priority groups take precedence. Good demonstration projects for dementia services have existed in a number of countries for some time, but they have not generally had much impact on policy formulation.

Box 1.1 Elements of service provision

The best match of service to need will often be achieved by addressing the issue of appropriate specialisation. All European healthcare systems depend to some extent upon generalist professionals identifying the healthcare needs ...