![]()

Section II

Basic Research

Movement as a Social Model

![]()

4 Dissecting a Social Encounter from Three Different Perspectives

Elizabeth B. Torres

CONTENTS

Introduction

Dissecting a Social Encounter through the Eyes of Different Research Areas

Behaviorist Account from a Psychological Perspective

Physiologist Account

Computational Neuroscientist Account

Guessing Mental States of the Other Party Is Hard and Highly Subjective

Integrating All Three Accounts to Explore Deeper Layers of Detail

References

Chapter 2 closed with the question, is it time for a new model of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)? The psychological and psychiatric constructs defining ASD today describe issues with social interactions in very narrow ways. The methods of inquiry about social and cognitive issues are more an art than a science. They have turned into a stumbling block in scientific advancement, preventing progress toward the discovery of possible causes linking early sensory-motor issues in neurodevelopment with differences in social exchange that emerge later in life. This chapter uses a seemingly simple social encounter to illustrate how, by adopting different perspectives, one can better appreciate and objectively quantify the complexity of the social dyad. Using the hypothetical accounts of a behaviorist, a physiologist, and a computational neuroscientist as they each describe the same encounter, we show that indeed there is more than meets the eye.

INTRODUCTION

Our physical bodies are in constant motion from conception. Even when we are seemingly at rest, our heart is beating, our lungs breathing, and our physiological systems are processing all sorts of electrochemical reactions involving, among other measurable biophysical processes, the transduction and transmission of information across many layers of our nervous systems. And yet, at rest all these motions occur largely without our awareness. We do not see them, and as such, we do not describe them as part of our movements; we do not associate them with what we more generally call behavior. The continuous stream of minute fluctuations in our subtle inner motions, together with our overt actions, may have a profound impact on how we behave, socially or otherwise. Certainly, if you have a stomachache caused by a bad chemical reaction from some spoiled food you ate, you would not be talking about poetry or concocting some clever joke to amuse a crowd of friends. Most likely, you just rather be left alone until it passes.

It must be terrible to not have that option, for example, as when having the physiology of your nervous systems in some continuous state of disarray that confines you to a lonesome existence in such a way you do not even realize, while others around you—perhaps unintentionally—interpret it as your being “antisocial” or having “low empathy.” Conceivably, if they knew of your actual physiological state of disarray, they would try to assist you. But how would they know that your physiological systems are out of whack? They cannot see that in any way, unless they wore some kind of “special glasses” allowing them to see beyond what their naked eyes can naturally capture.

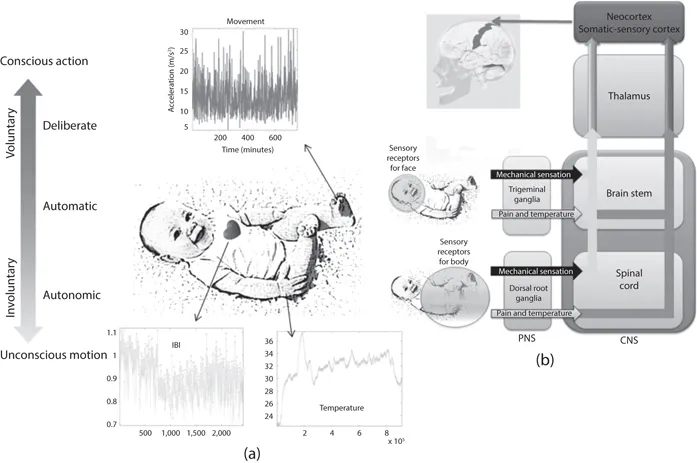

The minute fluctuations that occur in the motions that are sensed throughout the nervous systems can be measured with contemporary instrumentation and provide new lenses into subtle nervous systems’ phenomena. We have coined the waveform representing these fluctuations in biophysical rhythms micromovements (Figure 4.1 and refer back to Chapter 1), as we extract them from bodily and mental rhythms and turn them into quantifiable data output by the nervous systems of the person. Paired with proper analytics, the micromovements can provide a new kind of special glasses to see beyond the obvious and inform us of central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) interactions. To illustrate their use, let us first walk through a simple social situation as described by different (hypothetical) researchers, and then examine some social dyadic interactions using the micromovement perspective.

FIGURE 4.1 Extraction of micromovements is possible across different biophysical signals from physiological states registered in different body parts using wearable sensors. (a) Taxonomy of control levels involving different layers of micromovements mapping to different stochastic signatures. (b) Division of labor from early infancy during neurodevelopment impact different somatic motor networks in the face- and body-relevant dimensions of the social axes. (Reproduced with permission from Torres, E. B. et al., Front. Pediatr. 4:121, 2016.)

DISSECTING A SOCIAL ENCOUNTER THROUGH THE EYES OF DIFFERENT RESEARCH AREAS

Let us attempt to deconstruct the social encounter depicted in Figure 4.2. The encounter in question takes place between two people who may have seen each other once before. Through the length of time they sustain eye contact as they approach each other, they may admit to each other recalling their first fortuitous encounter sometime in the past, or they may right there and then decide to make the eye contact so brief that there is no ambiguity in their unwillingness to proceed with a social exchange. Notice here that this is a deliberate decision, rather than a spontaneously occurring event.

FIGURE 4.2 Genesis of a brief social encounter. Two fellows walking toward each other recognize their acquaintance from the distance and try to discern whether the other person is willing to admit to this mutual memory and engage in a brief social exchange, like a salutation and small talk. Body language involving sustained eye contact and facial microexpressions, including a smile, may give away the mutual willingness to stop, shake hands, and say hello. Alternatively, even a brief gesture like turning the body away from the interlocutor’s body midline and avoiding eye contact, perhaps accompanied by spontaneous (flat) facial microexpressions denoting an unwillingness to engage, will determine the fate of this brief encounter.

If their eye contact was sustained long enough to go on with the social exchange, they may further provide mutual evidence for their willingness to proceed by orienting their body toward each other and extending their hands to prompt a handshake—we will safely assume here that this is an acceptable social form of salutation in the culture where these two individuals developed. And finally, they will execute the handshake and say hello to each other, perhaps going on to initiate some social chat.

This is a very hypothetical situation. We shall dissect that social encounter using the lens of a researcher whose area of expertise has to do with social behaviors, another researcher whose area of expertise focuses on the physiology of the nervous systems underlying that social behavior, and yet another view through the lens of a researcher whose area of expertise is modeling the types of sensory-motor integration processes and sensory-motor transformations that may underlie that social behavior through the use of mathematical and computational tools.

Finally, let us examine examples of dyadic social interactions using a research program that integrates all three accounts through an interdisciplinary collaborative approach.

BEHAVIORIST ACCOUNT FROM A PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

To study this seemingly simple social exchange, the behavioral psychologist will most likely draw a discrete set of events and assign a discrete (ordinal) scale to each event unambiguously detected by the naked eye. The account may go as follows (for example): (1) eye contact, (2) smile, (3) handshake, (4) word exchange (“Hello!”), and (5) initiate chat. Each one of these five events may have a subscale, say from 1 to 10, with 1 signifying poor and 10 excellent, and some other considerations in between. The researcher will go on and collect data on each of these events (1–5) according to each of the numbers coded by hand to “quantify” the overall behavior. The behaviorist may then use traditional statistical tools and analyze the cross-sectional data by averaging scores across large numbers of subjects. This will build a normative data set with the potential to help identify atypical patterns in the future based on what is “normally” expected in such a social encounter (as defined by the inventory). Examples of such approaches abound in the fields of clinical psychology and psychiatry. In fact, these types of structured inventories are commonly used to gather criteria to diagnose disorders that involve social deficits as mental illnesses, as well as to treat them through behavior-reshaping methods or prescribed psychotropic medications (Lord et al. 1989, 2001; Lord et al.; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Notably, none of these clinical inventories ever characterized normative data, so they feature absolute ordinal values of some arbitrary scale. As such, they are not properly standardized.

PHYSIOLOGIST ACCOUNT

The physiologist will set up high-grade instrumentation using a variety of sensors to register signals throughout the nervous systems. Today’s technological advances allow for noninvasive methods of data registration. Using contemporary (e.g., wireless) instrumentation, the physiologist will attempt to continuously register every detail of this exchange. She may track the eye motions to assess the length of time on a millisecond timescale that person-to-person foveation was sustained, quantify the saccades and the smooth pursuit eye motions throughout the exchange, and record (for example) heat activity from the facial muscles using thermal cameras strategically positioned to capture various facial configurations and detect universal signatures describing microexpressions of the face (Ekman and Rosenberg 1997). Then these data will be used to automatically infer possible emotional states. The physiologist may also record neck motions (perhaps with wearable inertial measurement units and wearable electromyographic sensors). Neck position and orientation will reveal trajectories of the head in the body, and eye tracking technology will reveal the position and orientation of the eyes in the head. This information will enable assessment of the system’s use of different frames of references during sensory-motor transformations required in simple goal-directed saccades and hand motions. Simultaneously, bodily rhythms from all movable joints will also provide important information from each individual in the dyad and from their interactions as the multiple degrees of freedom in both participants coarticulate and the synergies dynamically fall in and out of synchrony. As the bodily rhythms fluctuate, so do the speech rhythms that the physiologist can record with a microphone.

The speech, generated by the sensory-motor apparatus from orofacial structures, will provide a rich body of data to—in concert with the face data—further help assess emotional components of the encounter. Likewise, sensors coregistering electrocardiograms and electrodermal activity (EDA) will provide several l...