![]()

Part I

"Image/Text Concatenations"; or, From Literary to Visual Cyberpunk (and Back Again)

Introduction

From the moment William Gibson opened his now-famous cyberpunk novel Neuromancer (1984) with the classic line, “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel” (3), cyberpunk has reveled in a literary-visual hybridity, or what Scott Bukatman in the foreword to this volume has productively called “image/text concatenations.” Gibson has remarked upon the importance of visual graphics in Neuromancer’s composition: The stories published in the French science-fantasy magazine Métal Hurlant were highly influential, notably Dan O’Bannon and Jean “Moebius” Giraud’s two-part serial “The Long Tomorrow” (1976). In his introduction to the incomplete Neuromancer comic book adaptation, Gibson states that “the stuff by those French guys, looked far more like the contents of my own head when I tried to write than anything I was seeing on the covers of SF paperbacks or magazines” (5). As a result, “it’s entirely fair to say, and I’ve said it before, that the way Neuromancer-the-novel ‘looks’ was influenced in large part by some of the artwork I saw in Heavy Metal” (5). Many of the papers in this collection will argue cyberpunk’s truest form is in its visual articulations, and the (ongoing) success of its print-based forms that are heavily indebted to visuality is testament to these assertions.

The ‘image/text concatenations’ exemplified by comic books and graphic novels, the former referring to serialized publications often collected in trade or omnibus format as opposed to the latter’s standalone narratives, have embraced a cyberpunk aesthetic and helped maintain its ongoing popularity as well as its relevance as a cultural formation, evidenced by Warren Ellis’s Transmetro-politan (1997–2002), Frank Miller and Geof Darrow’s Hard Boiled (1990–92), Paul Pope’s Heavy Liquid (1999–2000), Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell (1989–90; translations and sequels soon followed), Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1982–90), Robert Venditti and Brett Weldele’s The Surrogates (2005–6), Warren Ellis and Steve Pugh’s Hotwire: Requiem for the Dead (2009), Tony Parker’s 24-issue comic book adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (2009–11), Rick Remender, Sean Murphy, and Matt Hollingsworth’s Tokyo Ghost (2015–16), and so forth.

The five essays in Part One: “Image/Text Concatenations”; or, From Literary to Visual Cyberpunk (and Back Again) open this collection by focusing on the development of cyberpunk in print and print-based visual mediums in much the same way Gibson’s print description of the sky above the port relied upon the visual image of a television tuned to a dead channel. Whereas Gibson’s televi-sual vision evokes indecipherable static to describe the sky, the essays in this first section provide clarity into cyberpunk’s ongoing indebtedness to visual imagery, as expressed in text. Following W. J. T. Mitchell in that media are relaying images not language, that “[s]peech and writing . . . are themselves simply two kinds of media, the one embodied in acoustic images, the other in graphic images” (216), the essays in this section discuss the movements of images across media, from writing to drawing, from text to graphic.

The first essay focuses on a classic cyberpunk comic book: Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson’s Transmetropolitan (1997–2002). In “Beyond the Heroics of Gonzo-Journalism in Transmetropolitan,” Christian Hviid Mortensen demonstrates that this influential comic book series about gonzo-journalist Spider Jerusalem offers densely layered visuals within the panels to converge media-futurism and media-anachronism. This convergence helps create a McLuhanesque anti-environment that both critiques media forms but also, perhaps most importantly, invites, if not implores, the contemporary audience to resist the allure of a glittering culture predicated on pervasive media technology, celebrity culture, and a jaded passive audience.

Conversely, Timothy Wilcox examines a more-recent cyberpunk comic book series, Robert Venditti and Brett Weldele’s The Surrogates (2005), in “Embodying Failures of the Imagination: Defending the Posthuman in The Surrogates. ” Wilcox delves into The Surrogates’ handling of digital proxies and posthuman subjectivity to argue the series advocates not Spider Jerusalem-styled condemnations of monopolistic corporations or some Truth-inspired stance on the merits or pitfalls of surrogate technology, but instead the need for openness to the personal, everyday ways we encounter ourselves and others as posthuman subjects whose materiality is always already in flux thanks to ever-shifting technologies. This message is embodied, in part, in a consistently ‘smudgy’ visual style with a limited color palette that positions the world of The Surrogates as a liminal one where a posthumanist material presence is more valuable than a humanist real self.

Graham J. Murphy’s “Cyberpunk Urbanism and Subnatural Bugs in BOOM! Studios’ Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? ” evokes cyberpunk’s formative period by turning to the recent 24-issue comic book adaptation of Dick’s classic novel. While Dick’s original novel may not have been considered cyberpunk upon its original publication (in part because it technically pre-dates cyberpunk’s 1980s-era rise to prominence), BOOM! Studios’ comic book adaptation repositions the story as instrumental to a cyberpunk now given our current socio-political and cultural environs, particularly when it comes to a global climate crisis and our relationship to non-human animals. BOOM! Studios’ adaptation, one that reproduces the entire text of Dick’s original novel, deploys a ‘cyberpunk urbanism’ that hearkens back to the classic visual iconography of both Métal Hurlant and Blade Runner (Scott 1984), but Tony Parker’s artwork, particularly his panel work and shifting perspectives, resituate animals, real and synthetic, as a central focus in a manner generally obscured by Dick’s source text. What emerges in Tony Parker’s cyberpunk-styled envisioning of Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a visual focus on the tensions and cruelties visited upon the six- and eight-legged animals that crawl throughout the kipple-clustered corners of Dick’s original narrative and our own lives.

Stina Attebery and Josh Pearson’s “ ‘Today’s Cyborg is Stylish’: The Humanity Cost of Posthuman Fashion in Cyberpunk 2020 ” shifts our focus from comic books into refreshing, if not surprising, territory by exploring the role-playing game Cyberpunk 2020 whose print-based game manual codifies many of the cyberpunk motifs we’ve seen elsewhere. As Attebery and Pearson demonstrate, however, interactive textual descriptions work in tandem with a rule system and a referee to create vividly imagined situations, which means aesthetics are always at the heart of the gaming experience. In Cyberpunk 2020, however, players are encouraged to enact an explicitly posthuman aesthetic, but in so doing there is the subversion of the model of clothing and fashion as frivolous reflections of commodity culture. Instead, Attebery and Pearson show how fashion in Cyberpunk 2020 can destabilize subject-object relationships and invite players to create new ethical identities and experience an embodied posthumanism that engages with finitude and physical-psychological risks.

Paweł Frelik’s “‘Silhouettes of Strange Illuminated Mannequins’: Cyberpunk’s Incarnations of Light” returns to the scene of the crime by exploring the incarnations of light and electricity that flow seemingly unceasingly throughout cyberpunk’s earliest texts, beginning with the neon-saturated cityscapes of Gibson’s Sprawl or Scott’s Los Angeles and extending into the luminescent sublime that is a chief characteristic of not only such films as The Lawnmower Man (Leonard 1992) and its sequel Lawnmower Man 2: Beyond Cyberspace (Mann 1996), Johnny Mnemonic (Longo 1995), and The Matrix trilogy (Wachowskis 1999–2003), but also video games, including the Mass Effect franchise (Bioware 2007–present), and contemporary digital art. The ease with which Frelik moves across cyberpunk’s multi-media forms—from print-based sources to film and video games, to digital art—is evident in varying degrees in the previous essays, but heralds the essays that dominate the next section as cyberpunk’s ‘image/text concatenations’ give way to different media that extend cyberpunk’s visual iconography.

Works Cited

Gibson, William. Introduction. William Gibson’s Neuromancer: Vol. 1. Tom De Haven and Bruce Jensen, 5. Print, Epic Comics, 1989.

—. Neuromancer. Ace, 1984.

Mitchell, W. J. T. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. U of Chicago P, 2005.

![]()

1

Beyond the Heroics of Gonzo-Journalism in Transmetropolitan

Christian Hviid Mortensen

I’m not changing a fucking thing. I’m a writer. A journalist. I can’t change shit. What I do is give you the tools to understand the world so you can change things.

—Spider Jerusalem in Transmetropolitan: I Hate It Here 137.

There are two moments in William Gibson’s ur-cyberpunk novel Neuromancer (1984) that have proven to be quizzical for a 21st century reader first encountering Gibson’s classic cyberpunk tale. The first involves the now-famous opening sentence of the novel: “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel” (3). The image Gibson was trying to convey when the novel was written and published in the early 1980s was one of oppressive bleakness, the drab grey sky mirroring a ‘dead channel’ on the television; however, in an age of HD and smart TVs, a dead television channel is actually bright blue. Similarly, later in the novel, the protagonist Case is visibly disturbed to learn his deceased mentor, McCoy Pauley (a.k.a. the Dixie Flatline), has had his consciousness, his ‘self,’ recorded onto a cassette deck: “It was disturbing to think of the Flatline as a construct, a hardwired ROM cassette replicating a dead man’s skills, obsessions, kneejerk responses” (76–77). As with the 21st-century reader who would be forgiven for thinking the opening lines of Neuromancer project a clear-blue sky, the 21st-century reader living in a world of digital downloads and live streaming would also be forgiven to raise a quizzical eyebrow at the notion of cassettes and cassette decks in addition to the sheer improbability of recording an entire personality onto such a storage device.

These moments, while unintentionally funny or strangely awkward, exhibit the problems every science fiction narrative set in the near-future faces: What happens when the so-called futuristic technology is dated? Or, more precisely, what happens when the future has become our past? These moments of anachronism can prematurely date a narrative, turning it into a relic of a future that never came to pass; but, at the same time, the confluence of past, present, and a future (that never was) can be useful to advance observations, even social critiques, that continue to resonate with contemporary readers. This is exactly the case with writer Warren Ellis and artist Darick Robertson’s now-classic Transmetropolitan (1997–2002), 1 a cyberpunk comic book whose social critique and pleas to the readership to open their eyes is founded upon creating an anti-environment—i.e., a counter-situation that can provide the means of direct attention (McLuhan 1)— as a prerequisite for critiquing aspects of the contemporary media environment that otherwise escape our attention. As this chapter will show, Transmetropolitan as an anti-environment to the millennial media environment emerges in the convergence of media-futurism and media-anachronism.

1. Media-Futurism and Media-Anachronism

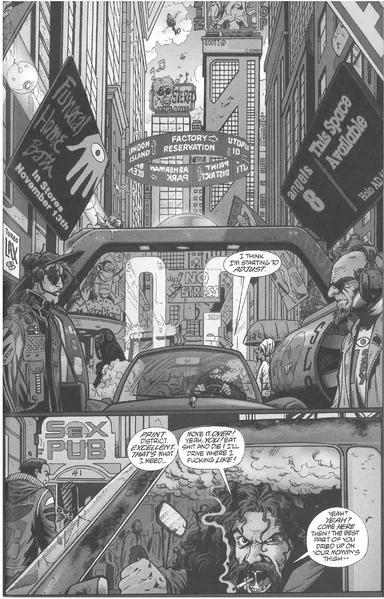

Transmetropolitan is the well-known narrative of a renegade investigative reporter battling corruption and power by seeking out and publishing the Truth. The story is set in the near-future fictional metropolis known simply as the City. As the principal artist throughout the series, Robertson carries a significant amount of the worldbuilding burden in Transmetropolitan, and it is a visually dense setting as befits cyberpunk.2 The protagonist, Spider Jerusalem, initially describes the City as “a loud bright stinking mess ” (1.18, emphasis in original) and with the density of ads, commercials, and graffiti on every available surface the streetscapes resemble what Jean Baudrillard has called an “uninterrupted interface” (127). Electronic billboard ads as we know them from Times Square have spread throughout the rest of the City, constantly assaulting the characters’ (and the readers’) visual senses as “blazes of nasty semiotics from an Adwall decoding with scary ease” (11.108). Characters may try averting their eyes by looking at the ground, but this is fruitless: even the sidewalks have been outfitted with screens. Transmetropolitan’s City is the embodiment of

a sort of obscenity where the most intimate processes of our life become the feeding ground of the media . . . today there is a whole pornography of information and communication, that is to say, of circuits and networks, a pornography of all functions and objects in their readability, their fluidity, their availability, their regulation, in their forced signification, in their performativity, in their branching, in their polyvalence, in their free expression.

(Baudrillard 130–1, my emphasis)

Baudrillard’s diagnosis of contemporary culture is fitting for the media environment of Transmetropolitan with the often sexually explicit billboard ads and reality

FIGURE 1.1 Transmetropolitan (1.15): The teeming metropolis of the City. Notice the rather bulky headsets on pedestrians, the naked women on the giant billboard atop the building in the middle and the musical notes indicating the noise/sound emanating from the ad for stereo implants at the building adjacent. Image Credit – TRANSMETROPOLITAN© Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson. All characters,...