![]()

Part I

Critical Perspectives on Women in Puppet Theatre

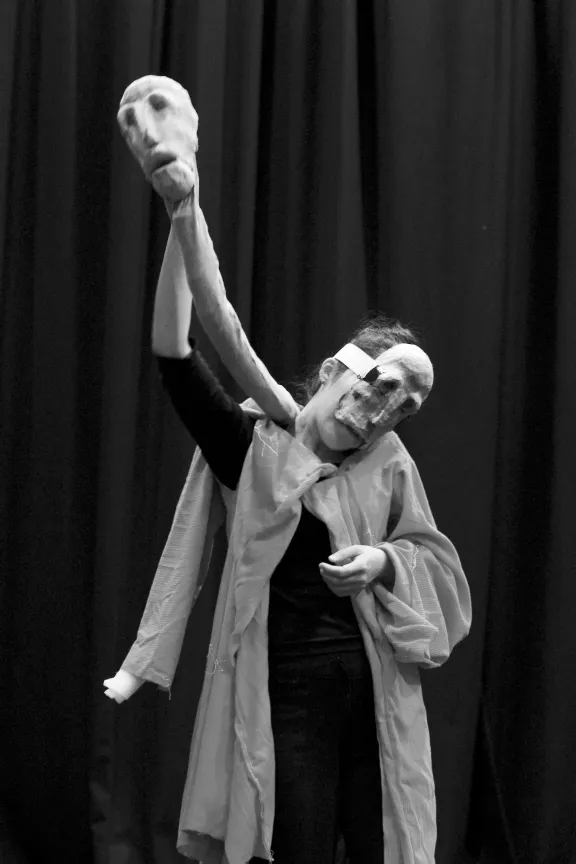

Figure 00.I Invisible Thread. Plucked – a true fairy tale, 2011, created by Liz Walker. Pictured: female protagonist.

![]()

1

The monster and the corpse: puppetry and the uncanniness of gender performance

As artists and audience mingled in the Bristol Old Vic theatre bar for informal feedback over drinks following a work-in-progress performance of Wattle and Daub’s chamber opera for puppets The Depraved Appetite of Tarrare the Freak,1 one male audience member expressed his annoyance at the design of the only female puppets in the piece, conjoined twins Marie and Celeste (Figure 1.1): “You need to make their lips and cheeks red, and give them long hair,” he explained to our puppeteer Aya Nakamura, “otherwise we can’t tell that they’re women.”

This ambiguity is telling; no one complained that the male puppets’ genders had been confusing. Much more labor must go into representing a puppet as female, illustrating Judith Butler’s claim that woman is a “term in process” (1990: 33) and revealing the myth of neutrality—the neutral body is read as male. What happens, then, when a “neutral” puppet, one without clear gender markers, insists on being female? Why might this be such an unsettling experience?

My company Wattle and Daub, for which I am co-artistic director, seeks to explore ways in which puppetry can engage in interesting and often unsettling ways with social constructions of bodies. My design of Marie and Celeste in Tarrare, with the help of Wattle and Daub co-artistic director Tobi Poster and puppet builder Emma Powell, intentionally resisted feminine tropes. I wanted this puppet to inhabit a similar aesthetic framework as the other, male, puppets in the piece. These puppets, apart from the character of the doctor who tells the story using the “bodies” in his autopsy room, were all designed around the idea of the corpse with sunken eye sockets, “decaying” skin, and partial bodies. It is important to note that the male puppets were not given any stereotypically masculine attributes, yet they easily read as male. Only Marie and Celeste provoked unsettled reactions from audience members.

This experience led me to reflect on expectations of gendered bodies, and reactions to bodies that resist these expectations. Ernst Jentsch and Sigmund Freud’s respective deployments of unheimlich (1906; 1919) and Masahiro Mori’s “uncanny valley” effect (1970) link the uncanny with ambiguity; as dead-yet-animated objects, puppets therefore find an easy home within this designation. A closer look reveals intersectional issues at play: Leigh Johnson, for instance, has linked the uncanny valley effect with racial ambiguity (2009), and John Bell suggests that by “tugging back on Modernism” the uncanniness of puppets productively unsettles our assumed mastery over the material world (2014: 49–50).

Figure 1.1 Puppeteer Aya Nakamura performing Marie and Celeste in work-in-progress performance of The Depraved Appetite of Tarrare the Freak. Puppet design: Laura Purcell-Gates. Puppet build: Laura Purcell-Gates, Tobi Poster and Aya Nakamura.

Taking the material world to include gender-constructed bodies, I extend this link by examining the uncanniness of the apparently neutral puppet body—a puppet lacking clear female markers such as long hair, breasts, red cheeks, or lips— performing as female. Connecting the construction of neutrality (the sterile body of the corpse unmarked by nonnormative identity signifiers) to anxieties surrounding contamination, I link this contamination to the monstrous body of the ambiguously female, overflowing in signification. I suggest that, while puppetry is a site for gender bias via the myth of neutrality, it also represents a subversive site with the potential to trouble and reveal such identity constructions through a productive uncanniness that asks us not just to experience but to linger within the ambiguity of the monstrous body.

Myth of neutrality

The labor that must go into representing the puppet body as female is one that I have witnessed countless times in my company’s beginning puppetry classes and workshops, run by Tobi Poster and me, when small groups of participants in university and theatre settings work together to build simple newspaper and tape puppets. We begin with a basic demonstration of how to create a human body with head, neck, torso, arms, and legs using newspaper and tape. No other instructions are given; we invite the participants to allow different types of puppet bodies to emerge within the limitations of this relatively simple model of constructing a human form. In groups of three the participants undertake their own versions of this style of puppet. The room is soon filled with simple puppets carrying no clear markers of gender; as we walk among the groups admiring their creations, the pronoun we consistently hear for these apparently neutral puppets is “he.” Usually one or two groups, having created their initial “neutral” puppet, decide to make a female puppet, designating femaleness through the addition of breasts, long hair, a dress—or, more often than not, all three. Femaleness in this context is both an afterthought and an addition.

When the puppets perform, they are puppeteered in a style adapted from bunraku by three participants per puppet (one on the head and arm, one on the other arm, one on the legs). The neutral/male puppets are either puppeteered with male-gendered performance markers (such as beating their chests or flexing arm muscles), which reinforce the puppet’s gender as male, or puppeteered in a relatively “neutral” style. “Neutral” is a tricky term; in this case it refers to the participants not making the puppet “do” anything that would read as stereotypical of a particular gender. Either way, the puppet is assumed by almost everyone in the room to be male. The “female” puppets—the ones with breasts, long hair, and/or a dress—are nearly always puppeteered using stereotypically female movements, such as swishing back the hair with an arm, giggling with hands over mouth, and bending at lots of joints: head tilted, hips jutted to the side, etc. While an entire study could be devoted to the gender performance of puppets in these sites, what is relevant here is that only the puppets with stereotypical female markers are performed as “female”; all other puppets—the ones that have no additions to their basic body construction—are either performed as male or, without particular gender performance markers, assumed to be male.

This is true of object puppetry as well in these sessions: Unless an object has a cultural association with femininity—such as being pink or a piece of jewelry or a tube of lipstick—it is assumed to be male, even when it has no specific cultural associations with masculinity. Our workshop participants tend to read a rock, a pen, or a cup as male by default. This points to the gendering of subjectivity as male in object theatre in which apparently “neutral” objects assume the status of subjects.

In Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism Elizabeth Grosz notes, “in lieu of any specification, one must presume … that the neutral body can only be unambiguously filled in by the male body and men’s pleasures” (1994: 156). Grosz’s use of “unambiguously” here is important; as subjectivity and its markers are almost universally male, a neutral body “filled in” by a body and desires of the female would read as uncertain. One need only look to the numerous examples of assumed male subjectivity to comprehend maleness as the universal subject position. In “ ‘Your Body’: Men Are People and Women Are Women” (2008) Lisa Wade examines the assumption that bodies are male in Bodies: The Exhibition. In this work female bodies are located outside of the main gallery space and only in the context of containing fetuses, posed in conventionally feminine ways, including as a pinup model.

Gwen Sharp extends this investigation in “Male as the Neutral Default” (2013), in which she posts images from Society Pages readers of consumer goods with two versions—one labeled without any gender markers (and often in the color blue), the other labeled with female markers (often, predictably, in pink). The unlabeled items, when positioned against the female-labeled versions, are clearly marketed to men, but, Sharp argues, maleness is sufficiently assumed, so no male labels are required. The items in their default state are for men.

A 2011 study (McGabe et al.) on characters within children’s literature found that not only are the majority of characters, particularly protagonists, male, but, when the gender of animal characters is not specified, readers, including women, nearly always label them as male when reading to their children. The first finding, that most protagonists in children’s stories are male, is relatively apparent, if often unnoticed. The second, that readers of stories featuring animals whose genders are unspecified tend to label them as male, is less apparent, as the creation of male characters is not revealed by an examination of gender pronouns fixed on the page but enacted in the moment of reading. The male-as-subject is both revealed and reinscribed through this act of reading aloud; the child being read to is learning both that males are the subjects of most stories and that the implicit rules of meaning-making through spoken language that interprets images include labeling subjects as “he” unless otherwise directed. This is an act of sexist relational meaning-making that I have observed in toddler singing groups with my sons; even when nearly every adult in the room is female (as is usually the case), the pronoun “he” is nearly always applied to any animal or adult not specified as female in the songs sung. As each of the five little monkeys falls off the bed, “he” bumps “his” head; the baby shark, “he” has a fin, a dorsal fin; the bear went over the mountain to see what “he” could see. I watch the female and male toddlers in the room as they participate in indoctrination into the male-as-subject, learning not just to repeat the words but which pronouns to draw upon in their developing constructions of subjectivity.

For Luce Irigaray, the male is the logos that will “reduce all others to the economy of the Same” (1985a: 74). In Speculum of the Other Woman (1985b), Irigaray employs a dialogic reading of Plato, Kant, Freud, Lacan, and other major male philosophers and psychoanalysts in order to illustrate that what they considered neutral or universal is masculine. She illustrates the ways in which this positioning of masculinity as neutral/universal serves to establish the male-as-subject and erase actual female bodies, substituting them with the feminine other created by men to serve men’s desires. The myth within this structure, Irigaray argues, is that equality between the sexes is possible, when, in fact, women’s difference within this symbolic economy is represented only as a lesser variant of the male. Women are positioned not as subjects in their own right but as the other to the universal male subject. For Irigaray, as explored in her later work, true equality between the sexes can only exist between sexes recognized as unique:

In order to go beyond a limit, there must be a boundary. To touch one another in intersubjectivity, it is necessary that two subjects agree to the relationship and that the possibility to consent exists. Each must have the opportunity to be a concrete, corporeal and sexuate subject, rather than an abstract, neutral, fabricated, and fictitious one.

(2000: 26)

South African puppetry artist and scholar Aja Marneweck draws on Irigaray’s transgressive female imaginary, as well as Julia Kristeva’s concept of the disruptive female semiotic alongside feminist theories of embodied knowledges, in her development of the “feminine semiotic.” For Marneweck the feminine semiotic is “a term that embraces postcolonial and feminist cultural theory in order to re-imagine where materialist and radical divisions might meet with puppetry and animism, and to imagine embodied knowledge strategies for feminine performance in South Africa today” (2016: 137). Marneweck is particularly inspired by the concept of the “inappropriate other,” a cultural and artistic strategy for interrupting conventional approaches to female representation developed by filmmaker and postcolonial theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha. The inappropriate other is both the same and different, as well as neither the same nor different. By occupying both an insider and outsider status simultaneously, this positionality allows for a transformative liminality: “In the body of the inappropriate other, definitions of clear-cut difference are destabilized and reinvented. The body expresses both separation and multiplicity. It is both defined and ill-defined, where boundaries become unstable” (Marneweck 2016: 139). For Marneweck, interested in threshold, hybrid practices (puppetry, animism) and multiple manifestations of otherness, Minh-ha’s “inappropriate other” allows for transformation through hybridity and liminality, destabilizing rather than reinforcing hierarchical or dualistic boundaries.

This kind of hybridity and liminality, as Marneweck points out, is particularly suited to the medium of puppetry, a form that simultaneously occupies multiple states, as I will explore below in relation to the uncanny. Through her concept of the feminine semiotic, Marneweck analyzes the “living sculpture” work of South African sculptor Nandipha Mntambo in her 2009 solo exhibition The Encounter, which includes a female/male hybrid figure in the piece Europa (2016: 148–153). Female/male hybridity can also be found in Australian puppetry company Snuff Puppets’ 2015 outdoor, large-scale, interactive puppetry piece Everybody, which features a giant naked puppet with both female and male genitalia. Andy Freer, artistic director of the company, describes their intention in this hybridity, however, as universalizing rather than destabilizing, recognizable rather than ambiguous, as the Everybody puppet is meant to represent the full spectrum of human embodiment and experience (Freer 2016, pers. comm., October 6).

The types of puppetry practice I am interested in exploring here enact a different sort of hybridity from that of the inappropriate Other or that of the universalizing figure of “everybody.” The humanlike, neutral puppet that I focus on—presumptively universal yet read as masculine—incites ambiguity not through a hybridity of physical markers but through its assumed gender (male) working at odds with its gender performance (female). I argue that this produces an uncanny effect driven by multiple binaries being unsettled, in...