eBook - ePub

Effective Augmentative and Alternative Communication Practices

A Handbook for School-Based Practitioners

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Effective Augmentative and Alternative Communication Practices

A Handbook for School-Based Practitioners

About this book

Effective Augmentative and Alternative Communication Practices provides a user-friendly handbook for any school-based practitioner, whether you are a special education teacher, an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) consultant, assistive technology consultant, speech language pathologist, or occupational therapist. This highly practical book translates the AAC research into practice and explains the importance of the use of AAC strategies across settings. The handbook also provides school-based practitioners with resources to be used during the assessment, planning, and instructional process.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Unit 1

Students with Complex Communication Needs and the Instructional Team

1

Understanding Students with Complex Communication Needs

Communication is a fundamental skill that is imperative to a child’s development. While many children develop their communication, language, and speech in a seamless manner, research suggests that there is an increasing number of children who display complex communication needs, also known as CCN (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013; Black, Vahratian, & Hoffman, 2015; Brady et al., 2016). Balandin (2002) defined CCN as a comprehensive term that encompasses a wide range of physical, sensory, and environmental needs that restricts or limits an individual’s independence. This includes an individual’s independence in communicating his or her wants and needs across communication partners. There are several factors that have been linked to the cause of CCN. These factors may include neurological disorders (e.g., cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, or autism), physical structures (e.g., cleft palate), genetic disorders (e.g., Down syndrome), and developmental disabilities (ASHA, 2017a).

Communication disorders are defined as an impairment in the ability to receive, send, process, and comprehend concepts or verbal, nonverbal, and graphic symbol systems (ASHA, 1993). Based on these definitions, it can be concluded that students with CCN have difficulties in any one or a combination of the aspects of communication, language, or speech (Jacob, Olisaemeka, & Edozie, 2015). Crichton (2013) explains that students with diverse communication needs may present difficulties, such as making eye contact, interacting with others, or engaging in or repairing a conversation when there is a communication breakdown. Needs in these components of communication can make conversations difficult for the student and the communication partner. Additionally, students who have difficulties with expressive or receptive language may have trouble using correct sentence structure, organizing a sequence of events, or finding the correct words to use (Binger & Light, 2008). These areas of need make it challenging for students to express their wants and needs and understand communicative interactions.

Over the past years, the prevalence of students with CCN continues to increase. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDOCD, 2015) states that nearly 17.9 million people have trouble using their voice. Furthermore, between 6 and 8 million people have some form of a language impairment (NIDOCD, 2015), and, approximately 4 million Americans are unable to meet their communication needs using natural speech (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013). Moreover, in a national health survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (2012), it was estimated that 55% of students with a communication disorder were receiving intervention services (Black et al., 2015). With the prevalence of communication disorders and services rising, it is expected that services will continue to increase in the classroom for students with CCN. Because of these increasing numbers, it has become even more important for educators to understand the various aspects of communication, how they develop, and how to better instruct and meet the needs of their students.

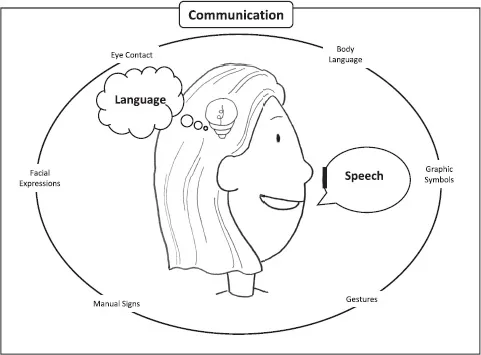

Understanding the Differences Between Communication, Language, and Speech

Communicative development begins early in a child’s life. The early interactions begin with the sharing of affection and attention. It is at this time the child begins to see how his or her behaviors have an impact on the environment (Colonnesi, Stams, Koster, & Noom, 2010; Hoff, 2014). For special education teachers to be effective elicitors of communication in the classroom, it is important that they understand what communication is and how it develops. Da Fonte and Boesch (2016) emphasized that “when special education teachers can recognize, identify, and provide meaning to the form and function of students’ communicative attempts, steps can be taken to increase or modify the student’s communicative skills to be more effective in a myriad of settings” (p. 51). Communication, language, and speech are closely related, but there are distinct differences between them (see Figure 1.1 for an illustration of this relationship).

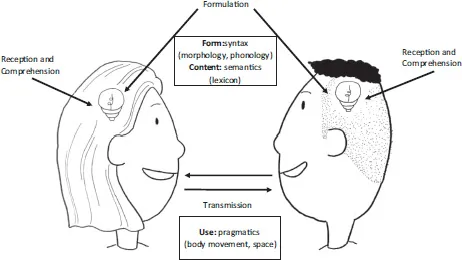

Communication

Communication is the process of sharing information among two or more people. The main goal of this process is for social interaction and involves four processes: (1) formulation, (2) transmission, (3) reception, and (4) comprehension (Shannon, 1948; Turnbull & Justice, 2016). Formulation is the act of pulling your thoughts together before sharing them with another person (e.g., feeling thirsty and wanting to request a drink of water). Transmission is the mechanics of relaying this thought to the person (e.g., saying “I’m thirsty. May I get a drink of water?”). This transmission process supports the last two processes of communication, which are reception, the receiving of the message (e.g., hearing the message that the person is thirsty and processing the information), and comprehension, the ability to interpret the information (e.g., understanding that the person has a need and is trying to meet it; Brady, Steeples, & Fleming, 2005). See Figure 1.2 for an illustration of this communicative process.

Figure 1.1 Relationship between communication, language, and speech.

Figure 1.2 A model of the communication process.

The goal should be for all students to become independent communicators. Independent communicators have the ability to share their personal ideas using an array of different modalities that they choose for themselves (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013; King & Fahsl, 2012). The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016) consider language to be a tool that plays a significant role in the communication process. It is crucial to remember that language is not necessary to communicate, as people can also communicate using nonverbal communication. Nonverbal communication can be expressed in many forms such as body movement, facial expressions, eye contact, and space or distance as well as features of the environment (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1998; Patrichi, 2013; Wood, 2016).

Language

Language can be defined as a system of conventional spoken or written symbols used by people in a shared culture to communicate (ASHA, 2017c; O’Hare & Bremner, 2016). There are three domains inherent in language, which include (1) content, (2) form, and (3) use (Bloom & Lahey, 1978). De Leo, Lubas, and Mitchell (2012) explain the domains by noting that the content of language refers to the words the student uses (vocabulary) and the meaning behind them (semantics). That is, how individuals select appropriate vocabulary to compose their message (Landa, 2007). Form refers to the words, sentences (syntax), and sounds (morphology and phonology) a student uses to convey the content of their language. Lastly, use refers to how language meets the social context, expectations, and demands during interactions. This is also known as pragmatics, the social aspect of language. This entails the knowledge of when, where, and to whom the student is communicating. Pragmatics skills are evident in infants well before they develop other language skills (Grosse, Behne, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2010). Considering all these components, it has been suggested that when a student demonstrates the appropriate use of semantics, syntax, and pragmatics, communication competence is achieved (Landa, 2007; O’Hare & Bremner, 2016).

Consider the example, “I’m thirsty. May I get a drink of water?” According to Landa (2007), the consideration of the words “thirsty,” “drink,” and “water” is referred to as semantics (content). Within semantics, these words were selected through a vocabulary system, called a lexicon, to convey meaning (Turnbull & Justice, 2016). When the student added the /y/ to thirst, they changed the meaning of the word, also referred to as morphology. The way the sounds were combined to form syllables and words (i.e., /m/ and /ay/ to create may) is called phonology. Morphology and phonology are used to structure sounds, syllables, and words into sentences (Landa, 2007). This structural piece is referred to as syntax (form). The facial expression, gestures, who the message was communicated to (communication partner), and eye contact used to relay the message “I’m thirsty. May I get a drink of water?” is called pragmatics (use). When considering pragmatics, you are determining if the student’s language is functional and how it is used to meet his or her personal wants and needs, such as effectively conveying their need for water (Landa, 2007; O’Hare & Bremner, 2016).

Speech

Often speech and language are used interchangeably. However, they are not the same. Speech is a voluntary neuromuscular behavior and only one of the ways in which language can be expressed (O’Hare & Bremner, 2016; Turnbull & Justice, 2016). In our example, after the student was able to formulate the thought of needing water by using language, he or she was then able to transmit this thought to the listener using speech. While speech can be used to transmit language, students may have the ability to produce typical speech sounds, but have difficulty with language and its various aspects (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

It is important to note that communication is not bound by language and speech. Communication can take place without these aspects. But, language and speech may allow the student to communicate in a more efficient and successful manner in the absence of other modalities (Martin, Onishi, & Vouloumanos, 2011; Turnbull & Justice, 2016).

Typical Communication Development

In order to better support the communication development of students with CCN, it is essential to first understand what typical communication looks like. This knowledge will help determine where the students are in their communication development (assessment), and how you will plan to enhance their communication skills (instruction/intervention). Table 1.1 provides detailed information on the typical stages of communication development.

Communication skills are often divided into two areas, receptive communication skills and expressive communication skills. Receptive communication involves the understanding or comprehension of messages and words that are expressed, while expressive communication involves the words and messages, both verbal and nonverbal, that people communicate to listeners (Lloyd, Fuller, & Arvidson, 1997). Figure 1.3 provides examples of specific receptive and expressive communication skills.

Receptive Communication Skills

Receptive language skills are closely linked to cognitive development (Owens, 2012). These skills begin to develop at birth and continue to develop throughout life. Receptive language skills are essential in demonstrating communicative competence (ASHA, 2017b; Wisconsin Child Welfare Training System [WCWTS], 2017). According to ASHA (2017b), early in the development of receptive language skills (birth to 5 months of age), children begin to recognize familiar voices, turn their heads to voices, and react to environmental sounds. During the second stage (6 to 11 months of age) children begin to understand the meaning of “no,” anticipate events, and understand some routine phrases (e.g., “time to eat”). In stage three (12–24 months of age), children begin to recognize the name of common activities, items, and people, and also begin to understand routine verbs (e.g., “eat”). Later in this stage, children begin to respond to simple requests, follow one-step directions (with and without a gesture), and begin to identify pictures in books, and body parts. By around 24...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the authors

- Acknowledgements

- Unit 1 Students with Complex Communication Needs and the Instructional Team

- Unit 2 Assessment: The Student and The Communication System

- Unit 3 Goal Setting and Implementation Practices

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Effective Augmentative and Alternative Communication Practices by M. Alexandra Da Fonte,Miriam C. Boesch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.