eBook - ePub

Communicating Emergency Preparedness

Practical Strategies for the Public and Private Sectors, Second Edition

This is a test

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Communicating Emergency Preparedness

Practical Strategies for the Public and Private Sectors, Second Edition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This fully revised edition of Communicating Emergency Preparedness: Practical Strategies for the Public and Private Sectors includes timely case studies, events, and references to articles and opinions about the direction of emergency preparedness communication. The authors draw upon their professional endeavors to inject a new sense of practicality to the text. New images displaying emergency preparedness campaigns are used to further illustrate the materials being presented. For instructors and practitioners alike, this book continues to provide the how-to instruction that is often required, and will only improve upon the success of the first edition in doing so.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Communicating Emergency Preparedness by Damon P. Coppola, Erin K. Maloney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Global Development Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Individual Preparedness

In Theory and in Practice

INTRODUCTION

Risk-related messages permeate all facets of modern life. Automobiles chime to remind us we must “Click It or Ticket”; cigarette boxes warn in no uncertain terms of the cancer threat contained within; lids on disposable coffee cups proclaim the obvious heat contained within; and pharmaceutical prescriptions are accompanied by pages of warnings and dangers that more than counterbalance the sentence or two that detail the intended benefits. The flood of risk information we receive can be so great that, in fact, we simply stop paying attention to most of it (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Click It or Ticket Campaign. (This image was developed by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration for use by the media, http://www.nhtsa.gov/buckleup/ciot-planner/planner07/index.htm.)

Every moment of our lives entails risk. And for every contributing hazard, there are actions we can take that will either increase or decrease our risk. For many—if not most—of these hazards, one might expect that common sense dictates the wisest risk reduction measures: holding a handrail while descending a staircase; wearing a seatbelt while driving or riding in an automobile; or avoiding cigarette smoke or quitting smoking. Regrettably, such simple and sensible actions are often neglected, and each year in the United States alone more than 1,600 people die by falling down the stairs; more than 10,000 people perish in motor vehicle accidents while neglecting to wear a seatbelt (accounting for approximately 40% of all daytime and 60% of nighttime accident deaths); and approximately 480,000 people succumb to smoking-related illnesses (one-fifth of all deaths that occur each year) (National Safety Council [NSC] 2007; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA] 2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2015). As a species, humans are ineffective at assessing or even estimating their own risk and likewise seldom prepare for or even fear the right things. Fortunately, through the application of effective risk communication, it is possible to correct risk-related misperceptions, miscalculations, and misguided behaviors at both the individual and population levels.

The majority of the risk-related messaging we encounter has been generated in the public health sector. In fact, the most common avoidable or reducible risks we face as individuals are those that fall within the public health domain. For decades, public health professionals have studied the most prevalent causes of mortality and morbidity, discovered appropriate methods for reducing them, and crafted effective messages and communication strategies to empower the public with this knowledge. Public health practitioners and health communication specialists have steadily improved their methodologies, resulting in increasingly greater population-wide risk reduction success. Through their efforts, people are living longer, healthier, and more productive lives.

Public health risks, however, constitute only one of the many categories of risk we face as individuals and societies. We also face financial risks related to our income, job security, physical health, and legal liabilities, among other factors; safety risks on account of crime, occupational hazards, our physical surroundings, and other factors; and risks from many other sources as well. There are also many larger-scale and occasionally catastrophic hazard risks that fall within the purview of the emergency management community.

Emergency managers and the various emergency services have been tasked with the heavy burden of preparing for, mitigating, responding to, and recovering from a full and growing list of natural, technological, and intentional hazards that each year affect millions of people worldwide and destroy property, infrastructure, and personal and national wealth worth billions of dollars. Like their counterparts in the public health sector, emergency managers are acutely concerned with population-wide risk. However, rather than addressing commonly occurring hazards that affect individual citizens on a more personal level—like heart disease and HIV infection—their foci are those disaster-triggering hazards that impact entire communities, cities, states, and even whole nations or regions.

Private-sector entities, inclusive of both for-profit businesses and nonprofit and voluntary organizations, are also concerned with the resilience of their own staff and, depending on the nature of their business, their customers, and supply-chain partners. The operations of a business or nonprofit organization will quickly become diminished or may even cease—even if the entity was not impacted directly—if its employees are unable to report to work. Private-sector entities are recognizing to an increasing degree that encouraging employees to address personal and household vulnerabilities (and even facilitating those efforts) greatly increases the chance of them avoiding interruptions and ultimately remaining in business if and when disasters occur.

Because the emergency management became professionalized much later than the public health sector, few emergency managers possess the requisite communication background or skills. For private and nonprofit risk management professionals, recognition of the need for individual preparedness in messaging and the availability of required communication skills beyond simple occupational safety and health are even less prevalent. And, in fact, outside of the public health profession in general, we find very few areas of specialty where the requisite knowledge and practical experience needed to develop and run impactful preparedness campaigns is common. And likewise we find few public- or private-sector offices that enjoy the leadership or financial support needed to adequately plan and fund campaigns or to gauge the effectiveness of those campaigns they manage to launch.

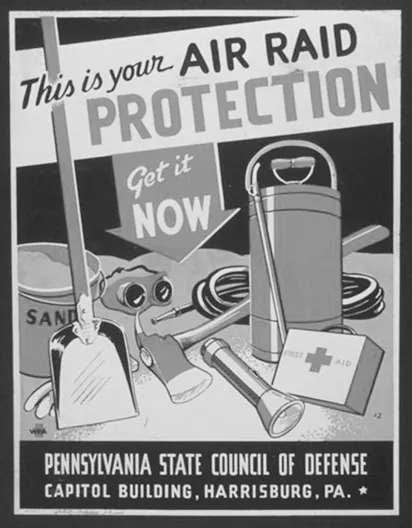

That being said, it would not be correct to accuse the emergency management community of being entirely inexperienced when it comes to individual and household preparedness messaging. In recent years, especially since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, there have been a number of awareness and training programs that seek or sought to reduce population-wide risk from major hazards (and likewise to reduce the post-disaster response burden on emergency services agencies). Some of the most memorable campaigns predate the watershed 9/11 attacks. For instance, almost every American over the age of 40 possesses an instinctive understanding of what to do when instructed to “Duck and cover!” An even larger population is familiar with the command “Stop, drop, and roll.” These two phrases, developed to address the risk of an air raid in the first case and one’s clothes catching fire in the second, are the products of two very widespread and successful disaster preparedness campaigns that were institutionalized throughout American public school systems in partnership with local emergency services (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Civil defense era poster, Pennsylvania. (Library of Congress 2000.)

Despite the wide success of these two examples, most public and private disaster preparedness efforts have failed to achieve similar levels of success. In fact, year after year, studies report that the vast majority of individuals and households have done surprisingly little or even nothing to prepare for disasters and hazards despite the increasing onslaught of information. The 21st century has thus far proven to be one marked by frequent and sometimes catastrophic hazards in the United States, including terrorist attacks, hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, blackouts, and much more. Even with extensive media coverage of these events, and the ongoing conduct of what may be one of the most widely touted disaster preparedness campaigns in decades (the Department of Homeland Security’s Ready.gov Website and its related Disaster Preparedness Month), recent research indicates that most individuals and families are still woefully unprepared for the risks they know to be affecting them (see Sidebar 1.1).

SIDEBAR 1.1 RECENT DISASTER PREPAREDNESS SURVEY FINDINGS

Year | Sponsor | Findings |

|---|---|---|

2014 | Allstate Insurance | 92% of Americans claimed to have been personally impacted by a disaster but less than 10% have practiced an evacuation plan and 30% claim they would disregard an evacuation order |

2014 | SUNYIT | Americans claimed to be knowledgeable about risk but only 1 in 3 had taken any efforts to plan for a disaster |

2014 | Energizer Holdings | Only 38% of Americans have an emergency kit at home |

2013 | American Red Cross | Only 1 in 20 coastal residents had taken seven key preparedness actions identified by the American Red Cross |

2013 | FEMA | Low levels of individual preparedness identified in a 2007 survey remained unchanged in 2013 |

2012 | National Geographic | Less than 15% of the U.S. population is prepared for a major disaster event, with more than 25% having taken no action at all. |

2012 | Adelphi University | Nearly half of U.S. adults do not have the resources or plans in place in the event of a disaster. |

Source: Citizen Corps Disaster Preparedness Surveys Database: Public, Businesses, and Schools, http://bit.ly/1QHtPiz.

The poor success rates of the wider emergency and risk management communities are frustrating, but they in no way suggest that the goal of a “culture of disaster preparedness” is unattainable. Organizations like the American Red Cross, in fact, have proven through the success of their cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and first aid training programs that ordinary citizens can and are willing to learn how to help themselves and others in emergencies. The Citizen Corps program has seen similar success with the Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) program. The knowledge and experience of these organizations that are directly attributable to their successes are not widely enjoyed in the greater emergency and risk management communities. Most notably, in the case of the American Red Cross, public preparedness efforts have bridged the gap between public health capabilities and emergency management concerns, and their practitioners have successfully incorporated the communication sector’s lessons-learned into their individual and household disaster preparedness education efforts.

Risk communication in practice is difficult at best, requiring a detailed understanding of the population targeted, the methods (channels) most suitable for reaching them, and the types of messages most likely to be received and acted upon. There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all risk communication message, and any attempt to do so is doomed to fail. By learning and applying the effective practices developed over many decades by the public health community and others, emergency managers and private-sector risk managers can enjoy similar levels of success.

This chapter introduces public (e.g., individual, household, or employee) disaster preparedness education and the concepts that guide its successful practice. To begin, a short overview of the experience gleaned in the public health sector, where risk communication efforts have advanced most significantly, is provided. This will help to familiarize readers with the relevant terms and concepts used by risk communication professionals, and the principles and theories that drive preparedness education and the behaviors desired. Finally, the foundational elements of preparedness education—its goals, limitations, and requirements—are presented and explained.

COMMUNICATION SCIENCE: A PRIMER

Communication science is a field of practice and research that has great potential to advance the preparedness efforts of businesses and communities alike. While all sectors and all professions utilize communication to some degree, the success of disaster preparedness efforts are wholly determined by the successful utilization of communication science principles. For instance, communication science explains how the mechanisms through which information is conveyed to individuals or groups will play an imminent role in the impact a message will have on the intended message recipients. Through the application of these lessons, which have been developed through decades if not centuries of research and practice and which have been presented in the chapters that follow, it is possible to influence positive behaviors and thus increase disaster resilience.

Research has defined the mechanisms according to which individuals process the information they receive through the following six distinct stages (McGuire 1968):

- Exposure to the message

- Attent...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Authors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Individual Preparedness: In Theory and in Practice

- Chapter 2 Managing Risk, Emergencies, and Disasters

- Chapter 3 The Campaign–Step 1: Early Planning

- Chapter 4 Step 2–Develop a Campaign Strategy

- Chapter 5 Campaign Implementation and Evaluation

- Chapter 6 Program Support

- Chapter 7 Emergency Management Public Education Case Studies

- Index