eBook - ePub

Risk Matters in Healthcare

Communicating, Explaining and Managing Risk

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The fundholding concept is now an established component of the NHS and is responsible for the growing influence of general practice in the delivery of health care. This book is comprehensive and authoritative, and a reference for GPs, practice managers and all those industries and professions providing services to general practice.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Risk Matters in Healthcare by Kay Mohanna, Ruth Chambers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Santé publique, administration et soins. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Understanding and talking about risk

CHAPTER ONE

Risk: What’s that all about then?

When it comes to risk management – everyone is an expert.1

We all automatically, maybe even subconsciously, make decisions in our daily lives that take into account the anticipated effect of likely outcomes. Often we are confident that we can predict the result of our actions and what it will mean to us if it does happen. Depending on our personality and our perception of risks and benefits, we will each make decisions that suit us and fit with the way we look at the world.

However, as Ulrich Beck acknowledged, risks can be ‘changed, magnified, dramatised or minimised within knowledge and to that extent they are particularly open to social definition and construction’.2 This subjectivity accounts for why there is such a wide variation in what we each consider to be ‘risky’ behaviour. Similarly, the results of previous ‘gambles’ – whether we survive or get our fingers burnt by our choices – will colour our judgement about the level of risk we perceive for a given situation.

So is it possible to produce one definition of risk that we would all recognise? We can say that:

risk is the probability that a hazard will give rise to harm.

Both the extent to which we judge that the harmful outcome is likely to occur and that to which we judge the likely outcome to be harmful, are subjective.

On the whole we tend to be overoptimistic about the risks we face. Most smokers acknowledge the connection between smoking and disease – although some, for a variety of reasons, deny it – but the extent to which they feel that risk applies to them is generally underestimated. Similarly, individuals tend to feel that advice about healthy eating and lifestyle applies to others. If asked to estimate the risk we feel that we face from heart disease, for example, or being involved in a car accident, there will be a bias towards optimism. Outcomes with a high probability tend to be underestimated. Interestingly, the risk we consider ourselves to be under from rare events, such as nuclear accidents, HIV, AIDS or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, tends to be overestimated.

So a misperception exists: a tendency towards the illusion of relative invulnerability, even complacency, where more common risks exist and one towards unnecessary concern for the less likely, but more newsworthy, events. Since perception of risk is a prerequisite for changes in behaviour, misplaced optimism may result in a barrier to preventative action. It is also true that the second type of error of perception can be a barrier to change. If we feel an increased sense of risk, especially when combined with low expectations for being able to deal with that risk, a ‘helplessness reaction’ may be provoked and obstruct intentions to adapt or modify behaviour. This has implications for the way doctors talk to patients about risk in an attempt to modify unhealthy behaviour.

In a similar way, some personality types will affect the way in which risk is allowed to influence our behaviour. Some people have a tendency to optimism despite the evidence. For pessimistic people, risks are assumed to be greater than they are, maybe as a self-protection mechanism.

All activity carries with it some level of risk; there is no such thing as absolute safety. Even so, our understanding and perception of the risk is influenced by our values and our experience. The value we place on our independence might colour how risky we feel it is to travel alone on the London Underground at night for instance, especially if ‘everyone I know does it and has never come to any harm’.

Even though it is clear that our values colour our thinking about risk, this cannot fully explain how it is that certain outcomes are less acceptable to the extent that we will take action to avoid them, even if very unlikely, or not take other actions that would result in clear benefits. An additional complication is that focusing on values is not in keeping with the usual situation where we are often asked to choose between alternatives rather than propose our ideal alternative for any course of action. Proponents of value-focused thinking, however, encourage us to consider values, not alternatives, in decision making as a starting place to understand difference.3 Our patients may tell us that although we may have all the statistics about risks of medical interventions, we don’t know how it applies to them in their circumstances. (In fact they may be wrong about doctors’ understanding of the statistics as well! More about that in Chapter 2.)

Consider a proposal to reduce fatalities in car accidents. Setting a speed limit of 20 miles per hour would reduce the number of crashes relative to a speed of 60 miles per hour. Such proposals, being put forward for inner cities, meet with strong opposition because they involve conflicting values – only one of which is reducing the number of deaths. Others have to do with convenience, saving time, cost and lost opportunities to do other things with the time that would be spent on the road. Since we almost certainly do not all hold identical value systems, this can result in decision making that others find difficult to comprehend. Proposals to decrease the speed limit on seemingly safe roads may infuriate those who drive for a living, such as lorry drivers and sales representatives. So in healthcare, just as in any other field, anticipated costs as well as benefits are taken into account by patients and interpreted in the light of what that outcome would mean to them, as they consider their options.

The extent to which we will tolerate the suspicion of risk then, is influenced by our preconceptions and beliefs, and our awareness of possible outcomes. We are influenced by what we see and hear. If a plane falls out of the sky, it will be reported on the news. The millions of successful flights each year go unmarked. A skewed or distorted image of the safety of aeroplanes as a form of transport can develop. Many people happily play the lottery every day without any idea of the ‘risk’ of winning the jackpot, spurred on by the success of friends and relatives winning ten pounds. Many continue to smoke, ever mindful of Uncle Fred who smoked till he was 98 years old and was knocked over by a bus on his way to the pub.

Availability bias leads us to overestimate the likelihood of future events happening if we have had similar events drawn to our attention, perhaps by the media. Confirmation bias results when new evidence is made to fit our understanding of how common an event is or our actions result in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Consider how often we have bought a new car only to suddenly notice them everywhere or how the experience of a miscarriage causes women to see pregnant women around every corner.

The understanding of how the world works, which guides our judgements about risk, might be described as background abstractions – paradigms, ideologies or beliefs – the set of shared assumptions that are formed through shared experience and that go unchallenged by those with whom we come into contact. The ‘fallacy of misplaced concreteness’ (wrote the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead in 1932) is the misperception that arises from confusing reality with one’s abstractions. The analogy of winning the lottery, sometimes used by doctors in an attempt to try and clarify or interpret the likelihood of certain outcomes for patients, can be subject to such a fallacy. A doctor who describes a rare outcome as ‘one in a million, like winning the lottery’ may be saying that there is a very small but measurable risk of a particular outcome. If that outcome is death, then some patients would want that information to weigh against the benefits. However, the doctor could be saying, or the patient may interpret what is said as, ‘that risk is so small it will never happen and is not worth considering’. Since the understanding of most lottery players of their likelihood of becoming a millionaire overnight is already delusional, the comparison is subject to the same misinterpretation.

A cautious person is likely to respond with diminished perception of the rewards of risk taking and a heightened perception of the adverse consequences of risk. This perceptual shift is mimicked in reverse for those considered by the cautious person to be reckless. Each would consider the other to be misjudging the outcomes, both good and bad, of an activity. This is brought into focus when we consider the opposing positions a seven-year-old and his mother would take about ice skating on a frozen pond.

Cultural theory

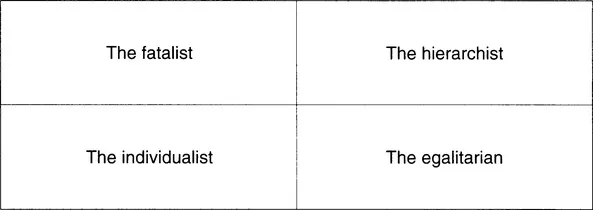

In an attempt to shed some light on the connection between ‘culture’ and an understanding of risk and subsequent risk-taking behaviour, cultural theorists consider one of the more popular models describing personality types. Here culture is described as the total map of our experience: the way we look at the world, what we have learnt from events in our lives and what we use to make sense of what happens to us.

Like all such models that attempt to categorise us into types, it is subject to the usual limitations. We may feel from the descriptions that we fall into different ‘boxes’ at different times of the day or month, or depending on the circumstances or decision to be taken. The usefulness of a model like this depends on how accurately it can predict how we will act in a given set of circumstances. Cultural theorists, however, have tested out this model in different settings to demonstrate how robust it can be.

Figure 1.1: The Cultural theory model of personality.3

Moving along the horizontal axis from left to right in Figure 1.1, human nature becomes less individualised and more collectivist. People on the left of the spectrum may be less good at being members of a team but could be either leaders or eccentric geniuses. Moving towards the right, individuals become more interactive, they may structure the world into those at the top and those at the bottom of the pecking order; good Toot soldiers’ for example, as they recognise the individual contribution to the whole. Along the vertical axis, we move from behaviour described as prescribed – constrained by imposed restrictions and resulting ultimately in inequalities – to that which is not governed by any predetermined rules and where choices are governed by individuals resulting in more equality. In ideological terms, a parallel shift might be from communism to commune. Each has, in certain circumstances, both strengths and weaknesses. If we attempt to classify ourselves into these types, the position we occupy will represent powerful filters through which to consider the risks of life.

Individualists are self-made people. free from control by others. They emphasise the individual responsibility to minimise personal risk. although they acknowledge the need for the development of social structures to allow collection and dissemination of information to facilitate this.

Individualists may perceive the risk of life as relatively stable, Tife is what you make it’. To be able to function independently, however, an individualist will recognise the responsibility of others to provide good information. They want the facts and then to be left alone to decide for themselves. These people are likely to ask themselves and their doctors, ‘What has been the outcome of this intervention previously in people just like me?’ They will have a strong sense of personal autonomy and resent any suggestion that the doctor knows best. In the role of doctor, the individualist may be more comfortable as a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the authors

- Acknowledgements

- Part One Understanding and talking about risk

- Part Two Clinical risk management

- Appendix: Sources of further information

- The Risk Ready Reckoner©

- Index