![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: the three kinds of consultation

Clinical, organisational and systems consultation.

Uses of systems consultation.

Complexities in healthcare.

An outline of the book.

A pre-emptive summary

The ‘consultation’ is the focal point of clinical and therapeutic work in healthcare, but in practice and in the detail the term can mean just about anything. This book discusses three main kinds of consultation: clinical consultation, systems or organisational consultation, and the consultation described in the following pages and which is a kind of informed partnership between the other two.

The first, clinical consultation, is an interview designed to elicit symptoms and signs, from which the clinician can make a diagnosis and plan treatment. It is at the very least the kind of question-and-answer encounter which computer fans (largely non-clinicians) have for some years imagined was the very essence of medicine, and could be carried out more quickly and efficiently by machine, nothing getting in the way of the essential logic and objectivity of the process. It is not as simple as that, however, and doctors and others have long been preoccupied with what it takes for the clinical consultation to work, from the old (and excellent) advice to ‘listen to the patient; he is telling you the diagnosis’ to accounts such as that by Pendleton et al. (2003). However, the core skills of clinical work are thoroughly established, central to mainstream training and already familiar as the focus of healthcare; this book is about something else.

Systems consultation has a tortuous pedigree (see pages 17 et seq and 29 et seq). It has been known as organisational consultation, inter-professional consultation or just plain ‘consultation’. This varied terminology is confusing but reflects, in the fields of health and care, developments over the years in techniques designed to help with the many extra-clinical issues that influenced diagnosis and treatment, including how we work and how we work together; the clinical interview’s penumbra, as it were. As clinicians we know the importance of extending into family work; but there is another kind of family, sometimes troubled, known to be dysfunctional from time to time and often in and out of trouble with the neighbours, and that is the clinical, academic or caring team. Systems consultation was developed specifically for work with professionals and teams.

This kind of consultation can be defined as the activity undertaken when one person (the consultant) helps another (the consultee) to work more effectively, by working through the consultee’s own perspective and helping to mobilise the consultee’s own skills. The consultant doesn’t ‘take over’; it is work-focused, not personality-focused, and the consultee is not subordinate, because it is a jointly undertaken peer-peer exercise. What to do with the outcome remains a matter for the consultee. Much of the rest of this book is about exploring the implications of this working definition. Meanwhile, anyone familiar with the caution, doubts and hot and cold war-zones involved in work within and across healthcare teams and their hierarchies will see the necessity for these ground rules. They are particularly important for dealing with territorial and role issues between professionals and professional groups, and for being interested in, understanding and respecting the roles, responsibilties and perspectives of others. Not all specialists are good at this; having evolved so many highly specialised areas, which we have needed to do, we now need specialists in working across specialties.

But if systems consultation can help us as healthcare professionals to work more effectively with each other, dealing with our private doubts about it as we go, is it possible to extend this kind of curiosity, understanding and partnership to our patients and clients too? This book explores this as well. To take this question seriously needs a strategy, not intent alone, and while systems consultation would be helpful alongside the clinical approach they cannot be merged seamlessly. The special value of the systemic approach is in its fundamental distinction from the clinical perspective; its enquiries and findings are different, sufficiently so to require a different identity and role from the purely clinical one. The ‘third kind of consultation’ therefore is not proposed as a hybrid formed of the other two, but as a kind of binocular, two-handed approach to all healthcare issues: the well-tried, well-tested and generally well-taught clinical approach on the one hand, and the relatively new but promising systems approach on the other. So you will find in the brand new medical bag I am recommending not one new piece of equipment but a pair, and I suggest we will be needing them both in twenty-first century healthcare, whose changes, chaos, complexity and increasing difficulty is already very well under way. In medicine, and in healthcare generally, we are going to have to move very fast to catch up.

Why ‘systems’ consultation? The term comes from Von Bertalanffy’s General Systems Theory (1968), which is about the homeostatic, multifactorial way living systems work. There is a brief account of its background and nature in Chapter 4.

For the moment I will describe it in these terms: when the doctor (or any other therapist) meets the patient, both have in mind some kind of conceptual model of the patient’s internal system, however complete or incomplete that may be on either side. We all know that doctors think in terms of nervous systems and circulatory systems and digestive systems and so on; most psychiatrists, psychotherapists and psychologists think along similar lines (although they may deny it) of real or imagined shifts in neurophysio-logical functioning, brain biochemistry, of psychodynamic complexes, structures, mental constructs and defence systems, of built-in repertoires of thinking (cognition) and behaviour, any of which may be assessed, evaluated and then treated.

The external system is even more elaborate. It is about the kind of person the clinician is, the nature of the relationship with the client (partly in the heads of both, partly outside), the whole machinery of the encounter from the status (real or imagined) of the clinician and the clinic to the equally part-real, part-attributed qualities of the patient and his or her background. It is even about the setting in which they meet and what the labels on the letterheading and the look of the place convey, or are meant to convey; this includes whether or not the latter is conducive to what doctor and patient are trying to do. It is about the real-life effects on the patient of, for example, a troubled partner, a stressful job, a bullying peer group, strains in school or college or in the culture or subculture; and it is about the kind of effect all these external realities have on the clinician too; his or her immediate colleagues, or people in other services whose help may need to be called upon; about training, supervision and support; about everything from the most elusive influences such as ‘image’, attitudes, myths and realities about healthcare, feelings, esteem and clarity of the job one is supposed to be doing, to such down to earth matters as time management, space, and whether the tools for the job (like the telephone system) work in a way which helps or makes things worse.

All this, I believe, is as relevant to what goes on in the clinical encounter and to every kind of therapy as the material identified as ‘internal’. But it is very hard to think about; in fact it is very nearly impossible, and there is always the problem that when subjects are so vast and complex we tend to introduce specialists and special language (jargon) or, even worse, acronyms. These protect us from thinking even as they set out to clarify. We tend to look to the core differences between specialties (e.g. surgery, psychotherapy, social work) rather than look for areas of connection; we set up journals, academic departments, exams.

It is bound to be that way, now and probably forever, and the point of the dual clinical/systems consultation described in the following pages is emphatically not some kind of all-embracing theory of how it all works or how it can all be made easy, but a multipurpose toolkit for finding a way though all this, and trying to illuminate the scene.

The usefulness of systemic consultation

As a joint exercise in looking at what is wanted, what is needed and what is possible, and in assuming that the consultee has more to contribute than even the consultee might have thought, it puts any shared enterprise on a surer footing. Whether as colleague or as client, the consultee has a solid role.

The focus on the autonomy and responsibility of the consultee (again, as fellow professional or as patient) tends to keep the problem near to where it started out. A problem in school remains with teacher and parents, instead of being reassigned as a clinical case in a children’s clinic. This may or may not reduce waiting lists, but it will certainly make possible a more rational response, for example by a consultative visit by a psychologist to a school rather than a child being simply booked onto a six-month waiting list for a two-hour assessment that it turns out isn’t needed. This in turn makes space in clinics for people who do need specialised assessment and treatment; what happens via systems consultation is that the criterion of needing specialist help is not only in the clinical signs, but in the answer to the question ‘how much can the front line people (patient, family, front-line professional) do for themselves, or at least contribute?’

If this makes sense then you will see that a consultative ‘valve’ all the way down the line (e.g. parent to teacher to school doctor to specialist and on to other specialists), at each step exploring what may still be possible at each step despite anxieties for a change, can reduce the number of people involved and supports continuity of care. Many treatments fail not because they’re wrong but because they aren’t used properly, monitored carefully and persisted with.

There is a cost in providing such consultative steps but it is a reasonable hypothesis that the introduction of consultative steps would save time and money. Consultation could also help make sense of waiting lists.

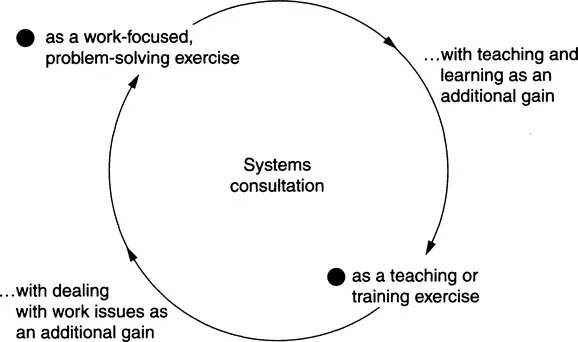

Very importantly, it is a joint learning and teaching exercise, consultant and consultee (colleague or client) knowing more for next time, for the present problem or for other problems. Clinicians end up knowing more about their colleagues and their patients (and their respective settings) than they did; patients learn hands-on healthcare, self-care and about prevention, linked to matters close to home. Such learning is problem-focused, that is to say the problem came first. But one of the attractions of the consultative approach is that it operates just as well the other way round: as teaching or training focused on day-to-day problems. Consultative approaches may therefore be arranged, or sought, primarily for problem-resolution, with hands-on learning as a ‘bonus’, or primarily for training, with problem-solving as the secondary but important gain.

Figure 1: Circular relationship between systems consultation in training and as a work-focused exercise.

The consultative process allows for the irrational and emotional (e.g. loss of confidence in persisting with a particular approach, or anxiety about asking for an explanation or an alternative) and trains those who practice it in practical empathic understanding; good intentions are not enough. The competent consultant must be genuinely curious about how and in what kind of environment the consultee functions, or tries to function, and against what odds. At the same time, respect for the other person is not about being polite, but about sifting through and actually negotiating openly what each is thinking about what the other can take on, about whether they can, or how much they can, and what help is needed. This goes both ways in true consultation, and a good test of ‘proper’ consultation is that role-reversal for a particular reason should not be a problem.

Given this kind of collaboration, with every question and doubt admissible, it is difficult to see how bad practice, bad behaviour on the part of patients (now perceived as equal partners, not irresponsible children), mutual ill-feeling, complaints, enquiries and litigation would not be significantly reduced.

Complications

The complexity of healthcare seems to have taken us all rather by surprise. The Golden Age of Medicine – always the day before yesterday – was simpler, as myths are. Doctors had wisdom and authority. Indeed, the less they could do, the more wisdom and authority was attributed to them. Nurses and perhaps a secretary did their bidding, unless the doctor was junior and the nurses very senior, when the question of who was in charge was reversed. There was something of the archetypal family in the practice or in the hospital – the wise old buffer, sometimes gruff but always kind, supported but kept in check with discretion by matron; and the youngsters, the junior doctors and nurses, working hard but having fun, cheeky and frivolous in their default settings, but capable of earnestness, indeed melodramatic seriousness, at the appropriate times. Other professions were hardly visible, though somewhere behind the scenes there were helpful magicians in the laboratory, the pharmacy and the x-ray department. Administrators, from the governors to the porters, were anxious to be of help, and, lest we forget, there were the patients too, whose chief attributes were gratitude and respect and, often, being interesting cases. And that was it, really: you had a pain, the doctor weighed it up and prescribed something for it, and you got better, worse or died. This may be a caricature and mythical state of affairs, yet an examination of even the most modern medical soap operas suggests that these archetypal ghosts still haunt the medical places.

Something has happened to medical care since. Chapter 4 is an attempt to outline some of the reasons for there being so many minefields and disaster areas on the horizon. For the moment, here is a list of some prominent problems on the contemporary scene, particularly those which consultative approaches might be able to help with. My shortlist has 13 main categories of problem.

1 Traditional authority – anybody’s – is no longer clear, and where it is clear it is neither automatically nor universally accepted.

2 Technical authority – that based on knowledge and skill – tends to be subject to controversy and challenge.

3 The relative ownership of rights and responsibilities are in a muddle, and this causes anxiety, resentfulness, suspicion and defensiveness.

4 Different members of the medical team have different and sometimes imperative views about their relative authority, rights, roles, skills and responsibilities. This can cause conflict.

5 There is in healthcare a need to be, to seem and to feel competent and in control, while the realities of healthcare largely operate against this. The psychological impact of this tends not to be acknowledged.

6 The high-speed advance of health science is producing unlimited possibilities and at the sa...

Figure 1: Circular relationship between systems consultation in training and as a work-focused exercise.

Figure 1: Circular relationship between systems consultation in training and as a work-focused exercise.