eBook - ePub

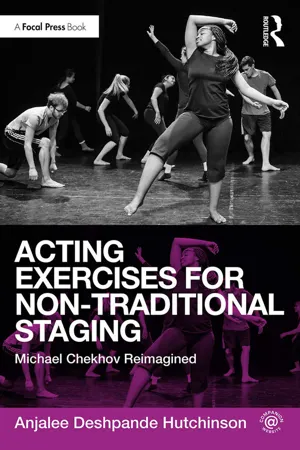

Acting Exercises for Non-Traditional Staging

Michael Chekhov Reimagined

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Acting Exercises for Non-Traditional Staging: Michael Chekhov Reimagined offers a new set of exercises for coaching actors when working on productions that are non-traditionally staged in arenas, thrusts, or alleys. All of the exercises are adapted from Michael Chekhov's acting technique, but are reimagined in new and creative ways that offer innovative twists for the practitioner familiar with Chekhov, and easy accessibility for the practitioner new to Chekhov. Exploring the methodology through a modern day lens, these exercises are energizing additions to the classroom and essential tools for more a vibrant rehearsal and performance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Acting Exercises for Non-Traditional Staging by Anjalee Deshpande Hutchinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Actuación y audiciones. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

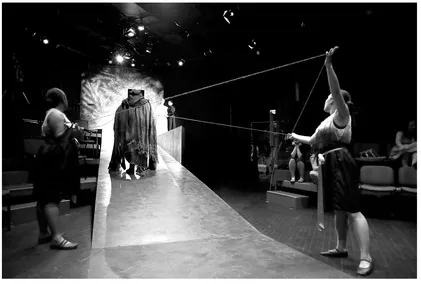

Blood Wedding by Federico Garcia Lorca, adapted by Caridad Svich. Alley-style production directed by Anjalee Deshpande Hutchinson, lighting design by Heath Hansum, set design by F. Elaine Williams, costume design by Jenny Kenyon. Bucknell University 2009. Credit: Enche Tjin

Credit: drawing courtesy of Pablo Guerra-Monje

1

An Introduction: Getting Comfy With the Weird Stuff

What Do We Mean by 'Non-Traditional Staging and Performance'?

If you would have asked me that question 25 years ago, I probably would have answered, ‘the weird stuff.’ My first experience with theatre was at the Fisher Theatre in Detroit. I saw a touring production of Annie with my father when I was 11 years old. I adored it. Then I saw Les Miserables, Phantom of the Opera and Cats, all touring productions over the next few years. I ate them up. I got involved with middle school and high school theatre, drama camps and community theatre. By the time I was accepted to undergrad, I figured I was something of an expert. Yeah, exactly. I was that student. You know the one. The first time I visited the college I would eventually spend the next four years at, I noticed one of their main stage spaces was somewhat different than what I was used to, it was not a box with a frame around it. It was not a proscenium. It was a thrust. I was put off. I thought it was a bit ‘hippy.’ I mean I knew they did weird stuff in the sixties but that wasn’t the theatre of today! Wouldn’t the audience on one side feel cheated? Can’t they just do normal shows?

Up until that point, I had never seen any theatre performed on a stage outside of a proscenium stage. That is because the great majority of popular Western theatre in this century has been staged in a proscenium-style stage space. It is usually our first exposure to theatre unless we are lucky enough to live in a place like New York or Chicago or Atlanta where other kinds of spaces prevail. Even then, you’d need to have had some very cultured parents who knew enough about theatre to seek out the more innovative productions and production spaces. The proscenium stage, although not really traditional in the historic sense of the word, is our inherited traditional legacy here in America.

When I refer to non-traditional staging and performance, I am referring to productions that are staged in the round/arena (where the audience is seated all around the stage which could be a square, circle, triangle, etc.), or on a thrust (where the audience is seated on three sides of the performance and the stage juts out a bit beyond the apron of the proscenium), or in an alley (where the audience is seated on two opposing sides of the performance—across from each other) or site-specific (which could be anywhere—many floors of a warehouse, a garden, a pit, a bridge, an abandoned asylum, a corporate high rise, etc.) But the term, ‘non-traditional’ is sort of a lie. The term is a misnomer. It would be more correct to call these types of productions ‘ultra-traditional.’

‘Communal Fire.’ Macbeth by William Shakespeare, directed by Anjalee Deshpande Hutchinson, set design by F. Elaine Williams, lighting design by Heath Hansum, costume design by Paula Davis. Bucknell University 2008. Credit: Mark Hutchinson

One can assume that before recorded history, theatre was storytelling—and storytelling in many early cultures was done around a communal fire. One of the first recorded histories of Western theatre dates back to 6th century bc. This theatre, one of the first theatres of the Greeks, is believed to have been in the round. Akin to sitting around a campfire, the circular theatre was an homage to a kind of circular dance of life, where the chorus sang and danced in response to the actors performing in the inner ring of the stage. Later in the 4th century, the shape became more of a semi-circle, where the audience sat on a hill watching the action on a wooden stage. By the 3rd century, the semi-circle remained complemented by raked stone seating but still out in the open air.

Meanwhile, in another part of the world, one of the earliest texts about Eastern theatre practice is the Natya Shastra by Bharata written sometime between 500 and 200 bc. In this text, three kinds of theatre spaces are described: square, rectangle and triangle. Although all are setup in a somewhat proscenium style, the author did describe in great detail that theatres should be small and intimate, and that the largest kinds of theatre were reserved only for the Gods. Humans would not be able to comprehend the stories told in the largest theatres (interesting when we connect this idea to William Shakespeare’s iconic quote, ‘All the World’s a Stage’, the world being an incomprehensible place sometimes). One of the earliest recorded styles of theatre was Japanese Noh, which was performed in a kind of obtuse L-shape where a bridge-way led to a platform and the audience was seated to one side of the ‘L’. Noh theatre also used a chorus, who sat at the side of the stage and sang, recited or played the music that told the story that the main characters enacted onstage. Kabuki also made use of the L-shape. This style enjoyed a shallow proscenium arch stage that was connected to the back of the auditorium by a raised bridge called a hanamichi. Drama was enacted on both the stage and the hanamichi.

Elizabethan theatre in the 17th century was influenced by classical Greek theatre and was often characterized by three tiers of wooden seating in a semi-circle around a wooden stage. The Globe Theatre in London, England (built at the turn of the century in 1599 which the modern replica is based on) is a perfect example of this kind of structure. Before long, there was a huge shift in world politics, which resulted in a transformation for the theatre. This change began in England. Back in the first days of the Globe when Queen Elizabeth was in power, the aristocrats and the commoners all shared in the experience of the performance, theatre was for everyone. During the reign of Charles I, there were more and more private theatres, which catered to the rich. Then during the English civil war in 1642, all theatre was banned in London and for 18 years there was a general assault against theatre in all forms all over England. The mind frame of the puritanical protestant authorities regarded theatre as being pagan and dangerous, citing the avarice of the romans from which it was born.

‘Pagan and Dangerous.’ The Bacchae; devised production adapted from Euripides, directed by Anjalee Deshpande Hutchinson, set design by Jenny Kenyon, costume design by Paula Davis, Lighting Design by Heath Hansum. Bucknell University 2011. Credit: Mark Hutchinson

When the monarchy was restored in 1660 by Charles II, theatres reopened, but the popular style of the time came as a swing of the pendulum with bawdy restoration comedies. Although the productions were open to all, the sexual explicitness and general morality in the plays reflected a taste expressed in patriarchal aristocratic circles, not in the general public. This type of play was a favorite of Charles II, who had enjoyed these kinds of shows in other parts of Europe when he was away during the war, and he encouraged the English adaptation of the form when he returned. The mind frame expressed by the puritanical protestant authorities remained with the general public. Gradually more and more theatres could only remain open if they began catering specifically to the rich. The experience of theatre to be enjoyed by the masses began to lose steam, first in England, then across Europe.

What we consider the modern-day ‘traditional’ proscenium arch that you see in most Broadway, regional and community theatres, as well as in most high school auditoriums, wasn’t really ‘invented’ until around the late 17th century in Europe. The raised platform was created with an arch around the front to simulate the illusion of a frame. This was in part a reflection of the needs of innovative new forms of theatre known as Neoclassical, Melodrama and eventually Realism. In the neoclassical form, the idea was to create theatre on a larger scale: intricate, grand and elaborate. In melodrama, illusion was key, the ability to provoke excitement through thrills and action! In realism, a different kind of illusion took hold. The utilization of the ‘the fourth wall’ was created to allow audiences the ability to peer into other people’s lives without them knowing. As you can imagine, this was super popular. Everyone wanted to be a spy into other people’s lives. Exciting!

At the same time, theatre architecture and interior design continued to grow more ornate with richly detailed gilded ceilings and velvet seating. Ticket prices went up and much of Western theatre settled into becoming the main pastime of the wealthy. But as the form evolved from restoration into neoclassical, melodrama and finally into realism, it stayed away from the more visceral components of the kinds of theatre that came before. Sure, there were always the exceptions (symbolism, expressionism, etc.) but the majority of popular Western theatre became locked into the tastes of the rich. The wealthy were not interested in the kind of theatre that came before, they did not want the actors too close or to have to be involved in a way in which they were not comfortable. In short, they didn’t want to work. They wanted to be entertained! This kind of theatre took hold of the modern world and became the most popular form of theatre from that point to this very day.

Yet something was lost in the transition. When going to the theatre became an expensive endeavor beholden to the whims of the wealthy, a kind of intimacy between performer and audience was lost. The audience became comfortable witnessing a play rather than experiencing it. Experiencing a play asks more from an audience and it is more difficult than just watching. Watching allows an audience to sit back and observe actors from a safe distance. Ever have a relative say, ‘that was very nice’ about a play you were in? That usually means they were at a ‘safe distance’ emotionally, intellectually and/or spiritually. Experiencing a play means being connected to the performance in a more visceral way. The audience has to be up for it. The audience has to want it. By the time realism began to grow, it became more common for audiences to disengage with experiencing performances in an active way and the clear delineation between audience and performer was created.

This was a huge disconnect from the more experiential theatre of the past. All the way from the time of the early Greeks to the theatre of the Elizabethans (and even longer in much of the Eastern world), a play was not a set of scenes to be watched alone, isolated in the dark but a story/ritual to be experienced with community. So how is that different? It is the difference between watching a televangelist on TV and actually going to church with your family. It is the difference between watching Star W ars on your laptop in your room or going to the movie’s premiere at midnight with some friends and a whole bunch of strangers, all dressed up as Han Solo, Princess Leia or Chewbacca. It is the difference between liking an Instagram photo of a friend at a wedding or actually going to that wedding and laughing with that friend or a bunch of your best friends. One is nice; the other is so much more. It is fulfilling or resonant or meaningful in powerful ways. Getting all your camping gear together, taking time off work, arranging everything with your friends—these are not ‘easy.’ But actually going makes all the difficulty worth it.

‘The Instagram Shot.’ Five Women Wearing the Same Dress by Alan Ball, directed by Anjalee Deshpande Hutchinson, set design by F. Elaine Williams, costume design by Paula Davis, lighting design by Heath Hansum. Bucknell University 2009. Credit: Mark Hutchinson

We have become a culture that is comfortable with convenience rather than a culture that seeks fulfillment. You know the latter is better than the former but actually doing it means you’ve got to battle your own inertia. Most people give up the battle before even starting. Some people don’t even know they are missing out. You know that great feeling of time spent doing something fun, something new or even something hard with someone whose company you enjoy? How about if that someone is new? How about when it’s a group of people? Now compare that to noticing that you just killed an hour looking at Facebook and now feel kind of ‘yuck.’ Not bad exactly. Just not good. Maybe like everyone is having a better time than you. Or maybe that everything is so superficial and nothing feels important. Or like you are becoming a sloth. And somehow this feels more comfortable than actually calling (or even texting) your friend and arranging to do something fun? Oftentimes even if we get that far, the ‘something fun’ involves more watching, less doing. Many of us would rather go to the movies after a hard week than try to arrange and go on a hike. Right?

And yet so many of us are longing for so much more. And this is where theatre can make a difference. Non-traditional staging, as we explore in this book, is an audience/performer connection that demands more than a unique configuration of staging or space. It demands non-traditional performance technique. It is about creating an experience for your audience that is more intimate, more resonant, more meaningful.

I am not saying that traditionally staged/presented theatre cannot often be fun, entertaining, moving or thought-provoking. I am saying that non-traditional staging and performance leans into what theatre is best at: the intentionally intimate shared experience. Film has a hard time creating a communal experience. Film is much better at realistic voyeurism—which is why the film industry is doing so much better than the theatre industry, because film creators are leaning into the medium’s strengths. When theatre makers lean into theatre’s strengths—those good ‘old fashioned’ ways of connecting to the audience—we allow the experience of performance to open new doors of meaning and revelation for our audiences and for ourselves. It often takes more expense and effort on the part of the audience to experience theatre than it does to experience film, so what is it that audiences get in return? Spectacle is great but in order for theatre to thrive, audiences need and want more. Non-traditional stagings offer a way to do that, a way to breathe the same air as the performers, to palpably feel the energy on stage and to give that energy back through focused attention, and to respond as a part of a community experiencing a story together.

Who Was Michael Chekhov?

Whenever I begin teaching Chekhov Technique anew, I always have a few students who confuse Michael Chekhov with Anton Chekhov, who was Michael Chekhov’s uncle. Anton Chekhov was of course the famous Russian playwright who wrote The Seagull, Three Sisters, Uncle Vanya and many other well-known classics. Anton Chekhov was born in 1860, died in 1904 and worked almost exclusively with master director and acting teacher Konstantin Stanislavski. Michael Chekhov (1891–1955) was one of Stanislavski’s actors, a part of his acting troupe and was reported to be a favorite of the legendary director. Stanislavski trained Michael Chekhov and Chekhov in turn became one of Stanislavski’s best students at the first incarnation of the Moscow Arts Theatre. A favorite not because he was his colleague’s nephew and had most likely grown up in and around the theatre, but because he had an exceptional...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 An Introduction: Getting Comfy with the Weird Stuff

- 2 Honoring the Obligation

- 3 Discovering the Delight

- 4 Embodying Three-Dimensional Resonance

- 5 Crafting the Rhythm of Truth

- 6 Sharing the Treasures

- 7 Entering the Experience

- 8 Conclusion

- Appendix: Short List of Exercises in Book Organized by Corresponding Michael Chekhov Tools

- Bibliography

- Notes on Author and Contributors

- Index