CHAPTER 1

Motivation and leadership in infection prevention and control

Annette Jeanes

In infection prevention and control, practitioners are frequently expected to lead, initiate or facilitate improvements or changes. The motivation and leadership of people is often challenging, particularly when associated with improving practice. This is even more complicated when you need to influence managers and leaders. The purpose of this chapter is to explain some of the theories and concepts associated with motivation and leadership and to suggest how these may be used within this specialty.

Theories Of Motivation

Kreitner1 defined motivation as ‘the psychological process that gives behaviour purpose and direction’, while Bedeian2 suggested it is ‘the will to achieve’. In this chapter the term motivation is used to describe the force that makes individuals do what they do, or perhaps what makes some staff wash their hands while others do not!

In ancient history, workers, slaves and servants were simply expected to obey and do the work. Their motivation was based on a need to eat and survive. Motivation was therefore relatively simple. In the current day some managers still believe that it is simple and that they know what motivates their staff, but this is a complex and developing field. Motivational theories vary and there is little consensus.

One traditional view of motivation is that people require tight control in the workplace and respond to reward and punishment. This is often referred to as the ‘carrot and stick’ method of motivation. Reinforcement theory3 is based on rewarding good behaviour and not rewarding behaviour that is not wanted. This method has frequently been used to train animals and has also been successful with humans; however, it is predictable and may in time dwindle in efficacy. It is the basis for awards- or prize-based systems and is used in performance management.

Frederick Winslow Taylor was an early pioneer in ‘scientific management’; he believed people were motivated by pay and worked more efficiently if work was divided into a series of tasks.4 Staff could be allocated a simple, specific task and be paid according to productivity. This approach was adopted widely in manufacturing industries – including Ford, where assembly lines led to greater efficiencies, although boredom with repetitive tasks caused job dissatisfaction.5 In addition, although workers were paid more if they worked faster, this could lead to lay-offs, as fewer staff were required and there was a lack of overtime, which was a disincentive. This prompted conflict between managers and workers, and actions such as ‘working to rule’ developed in response.

Elton Mayo conducted what are now known as the ‘Hawthorne studies’.6 These studies demonstrated that employee behaviour is linked to attitudes and that rewards are not just monetary. It was concluded from this work that just being part of a study or being observed and monitored changed behaviour and could improve or change performance. The ‘Hawthorne effect’ is often used to explain the improvements in infection control performance noted while observation is taking place. A good example is the improvements identified in hand hygiene compliance while observational monitoring takes place.7

McGregor8 believed that work was a natural requirement and that matching the developmental needs of individuals to organisational goals leads to optimal motivation and performance. In his ‘x’ and ‘y’ theory of management styles he argued that the ‘x’ type management style, which is autocratic and controlling, leads to poor results, while the ‘y’ type management style, which is participative, allows staff self-control and self-regulation, which in turn allows staff to develop and contribute more. Standardised and consistent infection control practice may be difficult to maintain and monitor in a self-regulated team if the team decides to do something different from everyone else; this may be challenging for infection control staff.

Herzberg9 concluded that there are two elements to motivation. The first comprises ‘hygiene’ factors, which include environment, supervision, relationships with others and pay. These factors can demotivate if they are inadequate. The second element is related to job satisfaction and is termed ‘motivational’ factors – these include recognition and achievement. This has been compared to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory,10 which places the basic physiological needs of food and shelter at the base of the hierarchy, followed by safety, social, ego and self-actualisation at the top.

The ‘motivational’ factors can be misinterpreted as a rehash of the ‘carrot and stick’ approach but it is more complex, as individual motivation varies. If you need to ensure people do what you want, it is important to understand what motivates them to do a job and consistently do it well. Herzberg9 argued that motivation accrued from monetary reward and was also associated with the recognition of value and achievement in the job. It can cause dissatisfaction if the pay is felt to be too little for the effort, but work has a purpose beyond earning money. Work can provide stimulation, responsibility, purpose and a structure to day-to-day life. It can provide a social network, and individuals become part of a group, which provides social and psychological support.

Vroom11 suggested that individuals are motivated by outcomes. These were termed ‘valence’, ‘expectancy’ and ‘instrumentality’; they drive effort, performance and reward, and they are shaped by individual beliefs and preferences. A healthcare worker could theoretically clean hands well and consistently because he or she believes it is an important part of infection prevention and that it contributes toward patient welfare (valence). The healthcare worker could put in extra time and effort because this would improve the standard of infection prevention achieved, which would be noted (expectancy) and which may lead to improved patient outcome and the associated kudos, recognition or promotion (instrumentality).

Other Factors that Influence Motivation

Workplaces and work groups also have a role in motivation, as they provide a communication network and a cohesiveness that links the group. The core values are generally shared by peers and dissent is discouraged, as dissent undermines the dynamics of the group and the status quo. Peer pressure is an important motivating factor in changing behaviours and embedding changes. Generally, people respond to peer pressure and aim to be accepted by their peers. Groups may be unaware that they hold negative values and perceptions, and this may influence their ability to assimilate or evaluate change or initiatives objectively.12 Alternatively, peer pressure can be a strong force in accepting changes or raising standards. There are many examples of peer pressure improving infection control compliance, including hand hygiene.13

Perceptions are also important and affect motivation, development and opportunities. The concept of the self-fulfilling prophesy or Pygmalion effect14 is that if opportunities are given and people are treated appropriately, they have the potential to achieve a lot, but that subconscious cues and expectations influence the overall performance obtained. Therefore, an optimistic and positive approach to change in the right circumstances may have a positive motivational effect. There is also a danger that focusing energy on non-compliant, poorly performing staff may demotivate the compliant staff, who may feel overlooked in the presence of the prevalent negative expectation; this may be the case in many areas of infection control practice, including waste disposal, isolation practices, screening, sampling and cleaning.

Job satisfaction is an important indicator of how individuals feel about their job. If this can be improved it may lead to increased motivation and even productivity, although the correlation between job satisfaction and productivity is tenuous.15 Job satisfaction may affect sickness and absence rates, contribute to staff turnover and affect behaviours of individuals within the organisation; however, it is affected by individual dispositions, characteristics and experiences.

To retain valued employees, some employers are now using approaches such as job sculpting.16 This designs the job to meet the needs of the worker, using the principles of optimising production developed by Taylor.4 Empowerment, autonomy, job enrichment, fulfilment and flexibility are all linked to increasing motivation. Developing and supporting an infection control link staff programme, for example, may lead to increased job satisfaction and motivation, as these staff are supported to develop a knowledge and skill set that may have a positive benefit.

Effective managers and leaders understand the value of motivation and use it judiciously. It is also important in infection prevention and control to understand the role of leadership and managers in change management.

Leadership and Management

Leadership plays an important role in change management and service improvement. Leadership influences change and often manipulates and manages change.17 There are many change management theories, but the classic original change model was developed by Lewin et al.18 This three-stage model – unfreezing, changing and then refreezing– essentially prepared the worker for change (unfreeze), made the change (change) and then ensured the change became permanent (refreeze).

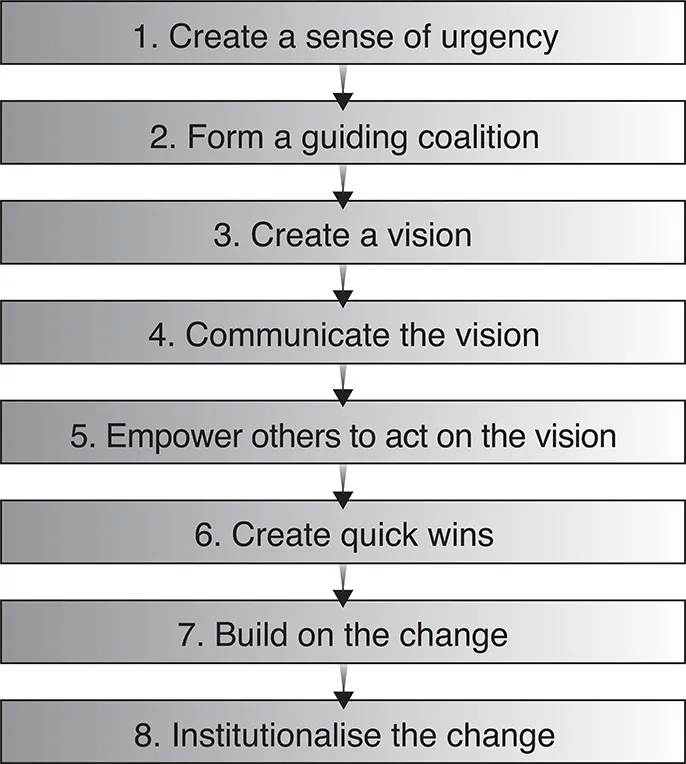

Another model commonly used is Kotter’s19 8-step change model (see Figure 1.1), which begins with what has been described as a ‘burning platform’. This sort of approach is used frequently in infection prevention and control strategies – for example, prevention of needlestick injuries, and reduction of the use of antibiotics.

The problem with models such as Kotter’s is that they are leadership driven and can be coercive. This may affect job satisfaction and motivation, which may also lead to resistance to change. Consequently, the approach to leadership or style of leadership is an important factor in change management. It can be influenced by a number of factors, including experience, values, beliefs, preferences, ability, culture and norms, the environments and the situation.

FIGURE 1.1 Kotter’s 8-step change model19

Leadership Styles

The classic leadership styles described by Lewin18 are autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire or delegative. Each style has its own positive and negative aspects. There are also various types of leader:

charismatic

participative

situational

transactional

transformational

the quiet leader

servant/authentic.

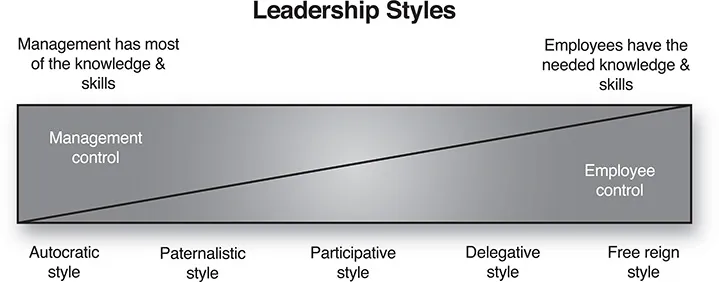

The style of leadership relates to the degree of managerial control. The less control the leader or manager exerts, the more control the worker or follower has, and the converse (see Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Leadership styles

A number of styles of leadership or management have been shown to produce poor outcomes, although they continue to occur:

toxic leadership or management20

post hoc management – a generally autocratic style, often only providing management after the event or in a crisis

micromanagement – very detailed and close management and control

seagull management – flies in, makes a lot of noise, craps on everything and then flies off again, leaving a big mess behind

kipper management – a two-faced manager with different approaches for different situations

the glory hog or user – takes the credit but does not do the work.

Many infection control practitioners will have encountered at least one of these examples.

The perpetuation of poor managers created by large organisations and by business schools has led to criticism. Sumantra Ghoshal stated: ‘Asshole management is not inevitable.’21 He observed:

It is interesting that a confluence of very diverse endeavours – that of economists to make the practice of management amoral, that of strategy and organisation theorists to make it scientific, and that of journalists and consultants to make it heroic – have collectively reinforced the rise of asshole management.21

Ghoshal argued that management should be a ‘force for good’ but that in the established and what he termed ‘old style management’ it was ‘solutions first, people second’, which led to an emphasis on the management of people to change.21

Axelrod22 proposed that an alternative to leader-driven change is collaborative leadership. Key elements of collaborative leadership are engagement, relationships and democracy. It is based on the principles of honesty, transparency and trust.

The Enron and WorldCom scandals prompted a desire for leaders who could be trusted, and this led to the concept and publication of Authentic Leadership by Bill George.23 The notion of ‘authenticity’ was already well established in counselling, psychotherapy and coaching. It is defined as being true to character, true to oneself; not living through a false image or false emotions that hide the real you, being genuine not a copy or clone.

Authentic leaders purport to know and live their values; they win people’s trust by being who they are, not pretending to be someone else or living up to the expectations of others. Character development, inner leadership or self-mastery is crucial to becoming an authentic leader.

Elements of authentic leadership:

being true to yourself in the way you work – no facade

being motivated by a larger purpose (not by your ego)

being prepared to make decisions that feel right and that fit your values – not decisions that are merely politically astute or designed to make you popular

concentrating on achieving long-term sustainable results.24

Popular use of the term ‘authentic leader’ and modifications has blurred the definition, the main overlap being with ‘servant leadership’.25 The concept of‘a leader who serves’ is well established, with one of the earliest references to servant leadership being Jesus Christ. Essentially, the concept is of a self-sacrificing leadership that prioritises the interests of the organisation and the well-being of workers.

There are number of problems with this type of leader in practice, such as ‘How long will such a leader or hero last? How can you be sure that their motives and values are genuine? How do they accurately determine the best interests of organis...