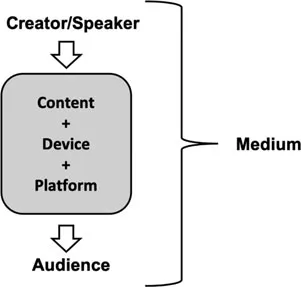

A number of media scholars have paid particular attention to what defines a ‘medium’. Many of these definitions bring together technology and the context that technology is created or used in. Andreas Hepp, for example, describes his use of the term ‘media’ as tied ‘quite closely to its everyday meaning: the set of institutions and technical apparata that we humans employ to communicate across space and time’ (Hepp, 2013: 4). Lisa Gitelman similarly frames media as a combination of technology and practices that she labels ‘protocols’ (Gitelman, 2006: 5–6; see also Jenkins, 2006). Amanda D. Lotz has taken this approach further, arguing that ‘[a] “medium” derives not only from technological capabilities, but also from textual characteristics, industrial practices, audience behaviors, and cultural understanding’ (Lotz, 2017: 3). This book takes an approach that draws on Gitelman and Lotz by understanding a ‘medium’ as a method of communication that is formed by a set of industrial, technological, textual and social relations. The industrial relations of a medium relate to the people and organisations who create/distribute content. The social relations involve the people who receive the communication and the context that reception occurs in. The textual/technological part of this definition, however, requires greater nuance within the context of transmedia culture. Each act of communication occurs through a combination of content, a screen device on which that content can be experienced and a distribution method or ‘platform’ that allows the audience access to that content (see Figure 1.1):

Certain combinations of speaker, content, device, platform and audience have historically been associated with specific labels such as ‘film’, ‘television’ and ‘gaming’ (or equally, ‘radio’, ‘comic book’, ‘novel’ and so on). A prominent thread in screen and media studies scholarship maintains the authority of these labels by promoting ‘medium specificity’, the idea that each label applies to a unique combination of creator, content, device, platform and audience.

Marshall McLuhan’s work, originally published just as scholarly attention was turning to media objects in the 1960s, has remained the foundational argument for medium-specific approaches. His statement that ‘the medium is the message’ (McLuhan, 2013: 19) frames a technologically determinist approach in which, as he later clarified, ‘any technology gradually creates a totally new human environment’ (McLuhan, 2013: 11). From McLuhan’s perspective, media determine the shape of human experience and interaction through their specific properties or affordances. The distinct affordances of a specific media technology lead to distinct experiences in using it. Lisa Gitelman retains this focus on medium distinction in understanding ‘new’ media spaces:

Just as it makes no sense to appreciate an artwork without attending to its medium (painted in watercolors or oils? sculpted in granite or Styrofoam?), it makes no sense to think about ‘content’ without attending to the medium that both communicates that content and represents or helps to set the limits of what that content can consist of. Even when the content in question is what has for the last century or so been termed ‘information’, it cannot be considered ‘free of’ or apart from the media that help to define it.

(Gitelman, 2006: 7)

Amanda Lotz also follows this approach in her exploration of the Internet and television but instead looks to the origins and textual affordances of content as defining the distinctiveness of media. She argues that ‘both film and television are audiovisual messaging systems, but they are distinct media because of their discrepant industrial formations, government politics, and practices of looking’ (Lotz, 2017: 4). For such scholars, different media, with different technological or textual affordances and contexts of production, are therefore inherently different in the way they shape their use and role within wider culture.

To a certain extent, McLuhan’s argument has formed the basis for screen scholarship in that medium specificity has often become intertwined with disciplinary specificity. Jonathan Gray argues that ‘media studies has been haunted by an apparent need to erect firm borders between media’ that emerged from film studies’ ‘long battle for legitimacy’ (Gray, 2010b: 812; see also Harrington, 2017: 4). As a consequence, screen and media scholarship associates each medium with a specific set of properties that distinguish them from each other and has led to distinct sets of academic concerns and questions. Despite film and television, for instance, both involving moving images and sounds that the viewer cannot change (beyond changing a channel) and are watched in communal semi-private spaces and the home (see, for example, Morley, 1986; Carroll, 2003), their corresponding academic fields have evolved differently. Television studies, for instance, has paid greater attention to how television fits within the temporal, spatial and social dynamics of daily life than film studies has for film.2 The evolution of early videogames studies was specifically based around debates over the distinctiveness of videogames from other narrative media and whether or not videogames could be considered ‘narratives’ in the way that film or television are.3 Such arguments prioritised the ‘unique’ qualities of videogames in allowing direct input from the player (see, for example, Juul, 2005; Carr et al., 2006).

It would be wrong to say notions of medium specificity have not been challenged within such scholarship. Television studies in particular has always grappled with questions around how television as a medium can be defined (see, for example, Silverstone, 1994; Spigel, 2004) and these debates have seldom offered rigid definitions of television (see, for example, Frith, 2000: 34; Brunsdon, 1998; Jacobs, 2011: 257). The more recent emergence of subfields such as audience studies, industry studies or media history has challenged medium-specific disciplines by cutting across film, television and games studies (or radio, music, theatre and so on) and further indicates the problems with dividing our ways of thinking by medium. Despite such considerations, though, the disciplinary divisions of ‘film studies’, ‘television studies’ or ‘games studies’ remain dominant within the academic publishing industry or university degrees and departments and perpetuate the idea that each medium has unique characteristics. However, such an emphasis is challenged further by transmedia culture. Christy Dena even argues that disciplinary adherence to medium distinctions has fundamentally limited the scope of work examining transmediality: ‘Indeed, the nature (to some extent) and breadth (to a greater degree) of transmedia practice has been obscured because investigations have been specific to certain industries, artistic sectors and forms’ (2009: 3). In order to understand how engagement within transmedia culture works, it is necessary to think above and across the established disciplinary approaches that enforce medium-specific distinctions.

The McLuhan approach of medium-specificity, arguably the very notion of ‘medium’ as the primary way to categorise screen content and experiences, therefore requires reconsideration in light of the emergence of transmedia culture and its explicit blurring of boundaries between content forms, technologies and devices. Although this blurring is not without historical precedence (see Bennett and Woollacott, 1987; Kinder, 1993 [1991]; Gray, 2010a; Bordwell, 2010 and, most notably, Freeman, 2016), the proliferation of practices that break down distinctions between ‘film’, ‘television’ and ‘game’ has grown exponentially in the last two decades. In his seminal book Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins uses the notions of media ‘convergence’ to articulate the development of multifunctional devices such as the smartphone and ‘divergence’ to define the spreading of content across multiple platforms. Calling on the work of Ithiel de Sola Pool, he argues that convergence and divergence are ‘two sides of the same phenomenon’ (Jenkins, 2006: 10). What both ideas have in common is that any clear distinction between ‘media’ at the textual, technological, industrial or social level becomes blurred or even vanishes completely.4 Any clear-cut technological distinction between media becomes broken when one can use a single device to watch a film, play a game, write an e-mail, surf the web, tell the time and a host of other media- and non-media-related activities. Similarly, what are the defining boundaries of ‘film’ when a film can be experienced in the cinema, on television or on a computer, may be produced by organisations and creators who are also making television and gaming content and that may borrow narrative or formal characteristics of these other media too? Screen engagement is increasingly inherently trans media, with the sense of moving between and across platforms being built into not only the practices it encompasses but the very term itself.

The emergence of transmedia culture challenges arguments for medium specificity by opening up increased variation and multiplicity in how content, device and platform (the grey box in Figure 1.1) can be combined and problematising any simple labelling of each combination. A quick example of Doctor Who (BBC, 1963), one of the most commonly referenced pieces of transmedia content (see Perryman, 2008; Evans, 2011a: 24–26; Harvey, 2015), demonstrates this. When Doctor Who’s first episode aired in 1963, it could only be experienced as one form of content (25 minutes of audiovisual material), through one device (a television set) and via one platform (broadcasting), as shown in Figure 1.2.

Now, through transmedia storytelling and franchising strategies, I can experience multiple forms of Doctor Who content, including audiovisual episodes, audio books, novels, games, educational challenges, merchandise, VR experiences and...