eBook - ePub

Learning from Delhi

Dispersed Initiatives in Changing Urban Landscapes

This is a test

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The inflexibility of modern urban planning, which seeks to determine the activities of urban inhabitants and standardise everyday city life, is challenged by the unstoppable organic growth of illegal settlements. In rapidly expanding cities, issues of continuity with local traditions, local conditions and local ways of working are juxtaposed with those of abrupt change due to emergency, reaction to modernity, environmental degradation, global market forces and global technological imperatives to make efforts to control by physical planning redundant as soon as they are enacted. In most third world cities there is little social welfare and almost no attempt at social housing.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Learning from Delhi by Written by Maurice Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Setting the Scene

Chapter 1

Field Research

Every year since 2002, each cohort of students have produced a booklet of their two-week fieldwork in India. This chapter reviews the scope of this work and its relevance for the architectural investigation of the everyday.

So why does a studio in a UK school of architecture base its design projects in low income settlements in India?

Students measure and document the physical and cultural context, interact with local residents, experience culture shock and, in the process, learn how to make Kanda and organise cricket games. Confronted with the difficulty of communicating without knowledge of Hindi or Urdu, students often have to rely on methods of non-verbal communication based solely on the profound richness of their raw observations. At first these attempts to communicate might prove difficult. How do you explain non-verbally that you are not a government worker, that you are here for purely educational purposes and do not intend to interfere with the running of the community? Sometimes such issues have been solved by simply arranging introductions to community representatives via a local non-government organisation, and occasionally this has been necessary for effective working. However some of the most insightful exchanges are those organised directly by the students themselves, often with the help of curious, energetic children but without direct, outside help.

Because of the language barrier and the lack of familiarity, students have to listen, question and decipher much more intensively than they would have had to do for a project based in London:

Surprises lay behind every physical or metaphorical corner. It is easy to take the environment and culture for granted in your own society – working in India was a wake-up call. Maybe some of us went with the intention to change the world with big gestures. Yes, the settlements have problems with their sanitation systems, few children go to school and the health care is often basic. But more importantly we encountered an extraordinarily rich and hospitable culture and people (Note 1, p. 3).

As part of their fieldwork students are asked to propose a design idea, a metaphor which would lead later in the year to an individual studio design project. A collection of some of these design ideas, which provide a powerful summary typology of the students’ spatial experience in India are summarised in this chapter, but first: a review of both the physical mapping and cultural exercises undertaken by the students to construct an understanding of place and space with some theoretical grounding for the methods employed.

Mapping: Physical Surveys

(1) Accuracy

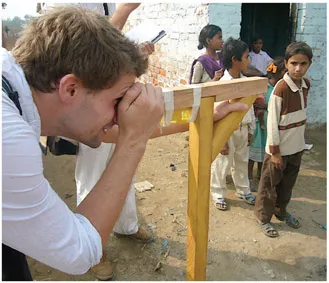

student measuring levels with a homemade theolodite Edward Ridge

Right from the start of their field trip, students are usually worried about the accuracy of the maps they produce. In Agra they had the benefit of a government map drawn for tax purposes which they found, when checked on the ground, to be highly inaccurate. Another base map had originally been drawn by the women of Kuchhpura to keep track of pregnant mothers and newborn children and proved more reliable. In South Delhi the Delhi Jal Board (Water Board) was able to provide an accurate map of the area of investigation which failed completely to represent the unauthorised settlements under study. They were just left as blanks on the sheet; a form of contemporary ‘terra incognito’ waiting to be explored. In Meerut, students obtained a detailed map of the old city drawn up by the colonial authorities towards the end of the nineteenth century and still being used today by the Meerut City Council: very accurate, but also out of date and missing a century of change.

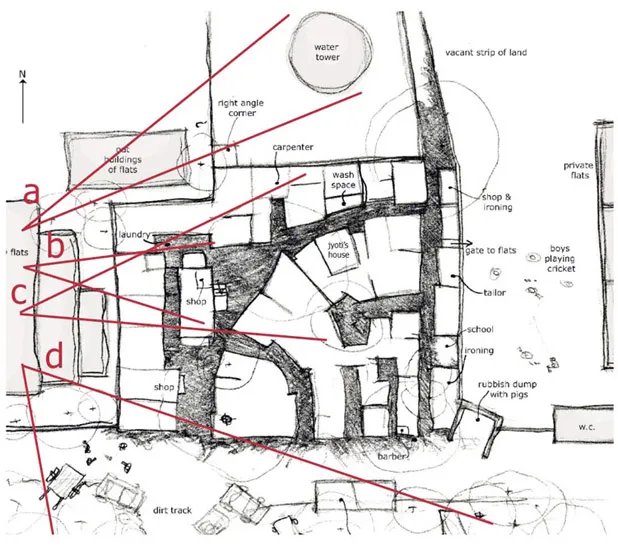

first viewing points for sketch survey Soami Nagar Camp Yanira de Armas-Tosco

In the last few years the availability of Google Earth has transformed the students’ ability to set out the main vectors of the unauthorised and previously unmapped settlements but even here buildings are often obscured from the satellite camera by tree canopies and the image resolution is often insufficient to pick up the details of place even at the strategic level.

In fact, on the ground, students have made every attempt to measure accurately but this was always a real challenge given very little surveying equipment and no previously established fixed coordinates. To overcome this, a range of innovative surveying tools was developed by the students including trundle wheels, theolodites, measuring sticks and the calibration of elevational photographs by including a measured child, Souraj, in each image. But this would not do for long distances:

The longest road was almost a mile long … then a boy on a bicycle rode past … he agreed to measure the road’s length using the revolutions of the front wheel. A small crowd formed. Chalk outlines at the start and finish were drawn to make it seem more like a race. Later we referred to Google Earth and found our measurements spot on (Note 1, p. 33).

One particular survey of the Soami Nagar J.J. (Jhuggie-Jhonpri) camp by Yanira de Armas-Tosco (2004 and 2005) was begun with the misapprehension that the area being measured was roughly square on plan but as soon as the team began assembling their information they noticed huge flaws and began once again, using the geometrical analysis of compass bearings taken at height, to give an overall framework to their more detailed survey measurements, methods pioneered by the early surveyors of colonial India (Keay 2000):

Bearings of major landmarks around the site were taken using a compass. There were very few sightlines through the camp so we had to climb trees and stand on roofs. Even then the density of the tree cover made it difficult to be accurate. Bearings were also taken of the direction of every street and all major walls to help tie all the detailed information together.

Overall street dimensions were then taken on the ground with a long measure which we constructed out of knotted string and some sticks. A detailed survey for each street was then carried out using a tape measure. Cross and diagonal check measurements were also recorded.

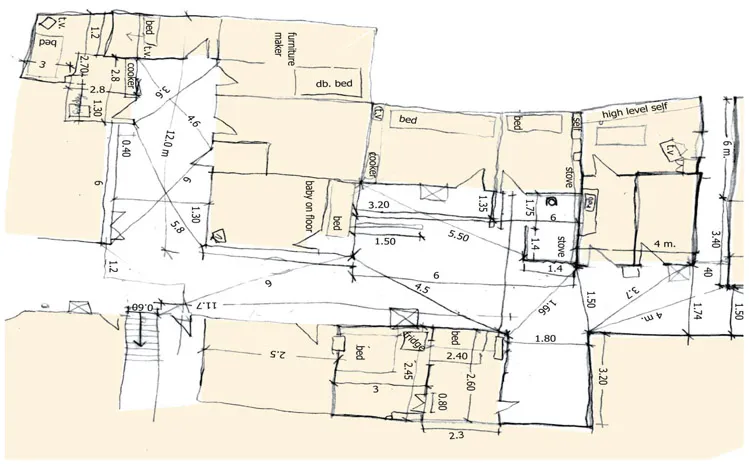

Information on the internal layouts of the houses was recorded along with the locations of beds, cookers, coolers and TVs (2).

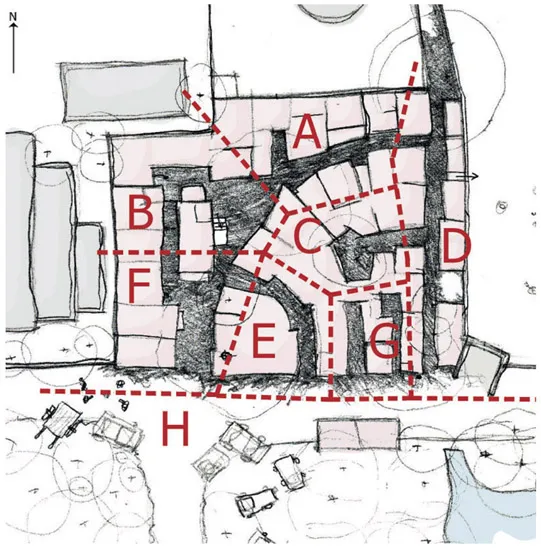

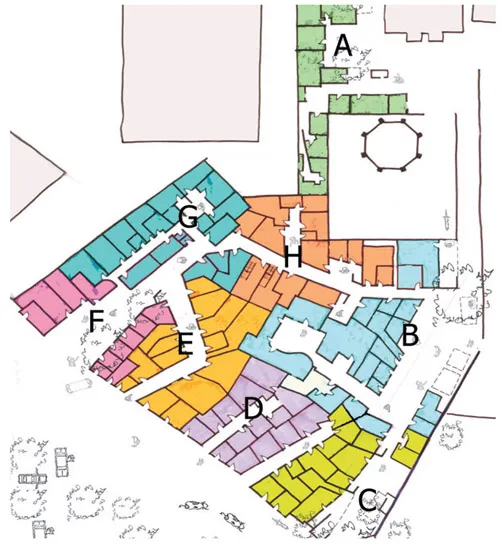

division of Soami Nagar Camp into neighbourhood survey areas Yanira de Armas-Tosco

Returning in 2005, Yanira found that there had been many alterations and extensions to the settlement in the intervening year. Some dwellings had grown a storey and temporary dwellings had been rebuilt in more permanent materials. The settlement seemed to be growing and changing before her eyes. Added to the student-led imperative for accurate representation in three dimensions was the need to record a 4th dimension: the speed of change.

measuring washing corner, neighbourhood survey Soami Nagar J.J. Camp Yanira de Armas-Tosco

Students were concerned to record as real and precise a set of physical dimensions as possible despite the rapid changes and the ephemeral nature of some of the objects and spaces they were measuring. It was sometimes hard to make judgments about appropriate scales to represent recorded measurements: when to focus down and enquire further and when to pull back and take a more strategic view. Given that in many cases settlements were being mapped for the first time and that the non-government organisation with whom the studio was working was likely to make use of their maps, students were concerned about their own responsibility for the accuracy of their surveys:

We are designing small projects on sites in four, unauthorised settlements based on our analysis, physical records and interaction with the residents. The information we collected is purely for this purpose. It is not sufficient or appropriate for official purposes and even though we have made every effort to ensure that it is precise, we cannot guarantee this (notes 1 and 3).

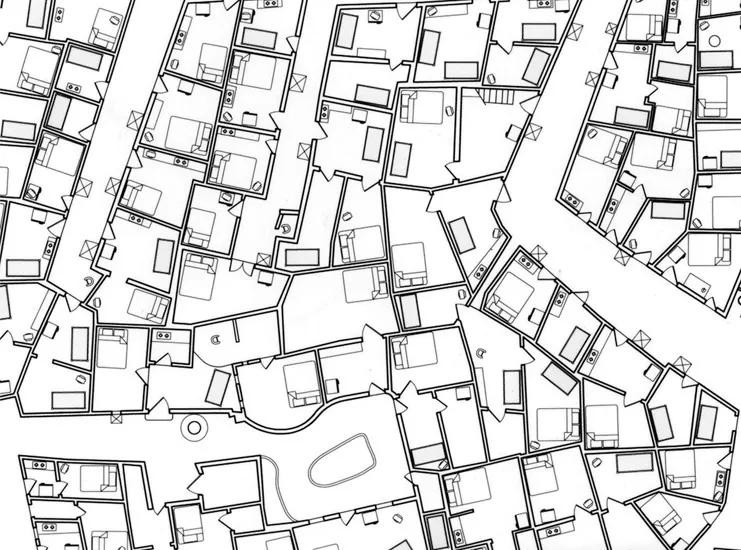

Learning from examples of student work from earlier years, more recent students have been able to perfect their hands-on survey techniques. Mapping the densely packed, multi-storied and crowded building mass of Chirag Delhi offered one of the greatest challenges.

Here, the tightly-packed and irregular buildings were criss-crossed by a web of narrow streets and alleyways. In response to the size and complexity, a team of six students, worked in pairs surveying at different levels of detail. Detailed surveys of the main squares were linked by a spider’s web of triangulated measurements taken along the alleyways:

This involved recording all the distances that made up the perimeter of the chowks using a measuring tape and marked up string for the longer spans. This was always a challenge as we were often the centres of attention, but soon the local kids became a cooperative rather than a disruptive influence on the measuring. By triangulating distances we were then able to pinpoint the location of trees and other structures within the chowks. We took level heights we could reach with the tape to inform sections and elevations [recorded in photographs] around the perimeter and later using an inclinometer to take several key block heights from surrounding buildings. By staggering readings to get around corners, this tool allowed us to track the change in levels from the central Dargah chowk to the town’s perimeter. By pacing out distances and sketching while walking we managed to piece it together bit by bit. We also found that by accessing rooftops we were able to develop the map more accurately and add information covering building heights (2).

detail of Soami Nagar Camp survey Yanira de Armas-Tosco

The supposed reliability of measurements is in contrast to the immeasurable qualities inherent in recording cultural exchanges covered later. Sometimes the two went hand in hand as a clear task of measurement often provided access to the community.

… every single family welcomed us into their houses to measure and Rahul was able to interview many people while Helen and Yanira ran around with the tape measure (2).

(2) Morphological Tales

Nick Maari recognised in the topography of the poor, illegal and overwhelmingly Sikh, East Delhi settlement called Kalyanpuri Block 19/20, which he surveyed in 2007, the physical expression of what Evans has called ‘the terrors of over communion’ (Evans 1997, p. 42). In Delhi he felt that the main issue was that:

There was too much of everything going on, too much noise, too many people, too many cars, too many rickshaws, too much poverty, too much extravagant wealth and too much garbage (4).

overall plan of Soami Nagar J.J. Camp Yanira de Armas-Tosco

Nick’s original impression was that Block 19/20 was a typical example ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Forewords

- Introduction

- Part 1: Setting the Scene

- Part 2: Essays

- Part 3: A Catalogue of Selected Student Schemes and Live Projects

- Students and Projects 2002–2010

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index