Andrea Alciato’s name appears in early publications as Andrea Alzatus, after the village of Alzate near Como, where his family originated, but Giovanni Andrea Alciato, as he is known to the world, was born in Milan on May 8, 1492. He received his early education there under teachers who included Parrhasius, Lascaris, and Chalcondyla, from whom he acquired his exceptional mastery of Latin and Greek and his sophisticated philological technique. At the university of Pavia he studied law under Giasone del Maino and Filippo Decio, and then moved to Bologna in 1511 to continue under Carlo Ruini, eventually taking the doctoral degree in both civil and canon law at Ferrara in 1516. From as early as 1515 he was to publish a series of outstanding legal works that applied the philological lessons of Poliziano and Budé to the restoration of the texts of Roman law, not only of the Digest but also of the lawyers of the earlier empire whom Justinian had pillaged and fragmented, and even of the earliest Twelve Tables.1 It was an undertaking that earned him the reputation, with Budé and Zasius, as one of the great “triumvirate” of humanist lawyers of his time.2 As early as 1508 he had also essentially completed an historical and philological study of Roman inscriptions in the Milanese,3 which, though it remained unpublished, formed an important element of the posthumously published Rerum patriae libri IV and was eventually recognized by Theodor Mommsen in the nineteenth century as a significant contribution to the history of epigraphy.4 Other historical works included a letter to Galeazzo Visconti, originally published as a preface to his Annotationes in 1517, and later known as the Encomium historiae, which sought to restore the reputation of Tacitus alongside that of Livy.

In the autumn of 1518, with the help of Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, his principal Franco-Milanese patron, Alciato took up a teaching post in the university of Avignon, where in 1520 one of his students was Boniface Amerbach. The latter was already in close touch with Erasmus and Zasius, and it was through Amerbach that Alciato’s letter to Bernard Mattius, later known as the Contra vitam monasticam, was passed on to Erasmus. Fear that the letter might become public caused Alciato much concern when, in the first years of the Lutheran dispute, he sought to conceal his early reformist leanings.5 In 1521 he was made a count palatine by Leo X, giving him the right to award doctorates. It was during this Avignon period that he modified his early philological approach to include more attention to the medieval commentators, developing a broader conception of jurisprudential methods which characterized the teaching that earned him his European reputation. He left Avignon in the autumn of 1522 after a dispute with the authorities about his stipend. From 1522 to 1527 he taught in Milan, suffering considerable losses during those troubled years, especially as a result of the Battle of Pavia.

In 1527 and 1528 he returned to Avignon, but was able to move, under much better conditions, to Bourges, where he was honored with the presence of François I in his inaugural lecture. His treatise on dueling, De singulari certamine, was written to support the king in his dispute with Charles V. In Bourges from 1529 to 1533 his fame as a teacher reached its peak and his presence there was largely responsible for the development in France of the historical school of law.6 However, after negotiations with both Milan and Venice, Alciato was obliged by the Duke of Milan to return to Pavia, where he spent four rather difficult years. In 1537 he was reluctantly allowed to take up a post in Bologna, where one of his students was the emblem writer Hadrianus Junius. It was at this time that he began to publish his Parergon iuris, which were mostly philological notes from his wide reading in literature and history, accumulated during his work on legal texts, but reflecting also his particular interest in Plautus.7

In 1542 he was obliged by the imperial authorities to return to Milan. War again gave him the opportunity to move, this time to Ferrara at the invitation of Ercole II d’Este, but he was again obliged by the imperial authorities to move back to Pavia in 1546. Student indiscipline and the gout made his remaining years difficult, although his reputation remained undiminished. He died in Pavia in the night of January 11–12, 1550.

The emblems

That Alciato was in fact the father and initiator of the illustrated poetic genre which is now called the emblem is not in doubt.8 It was, in large part, the fruit of a hobby, translating Greek epigrams,9 that he had cultivated, it seems, since his youth.10 Some sixty of his translations appeared with others by well-known contemporaries, including Erasmus and Thomas More, in an anthology published by Bebelius in 1529. During the 1520s he seems to have developed the idea of the emblem; the Emblematum liber, printed – although without his authorization – by the Augsburg publisher Heynrich Steyner in 1531, was the first printed work to use the term in its title. It launched what was to become an immensely influential genre of illustrated books. This first edition contained 104 emblems; the second, authorized edition, by Christian Wechel of Paris, added another nine, and two more were added by the same publisher in 1542. A second collection of eighty-four new emblems appeared, after maneuvers which remain something of a mystery, from the house of Aldus in Venice. The two collections were combined, though still as two separate parts of the work, by Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau of Lyon in 1547, and the total was brought to 212 by various additions made in the editions published by Guillaume Rouille and Macé Bonhomme in Lyon between 1548 and 1550. In these editions Barthélemy Aneau, who was primarily a teacher, rearranged the emblems, apparently with Alciato’s approval,11 to form a sort of commonplace book. This became the more common form of the work, but the two formats existed side by side until early in the next century, suggesting that there were readers who not only used it as a commonplace book but also enjoyed it for the pleasure of the unexpected in reading, which Aneau obliterated when he reorganized the work.

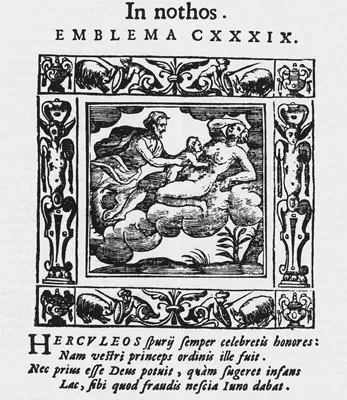

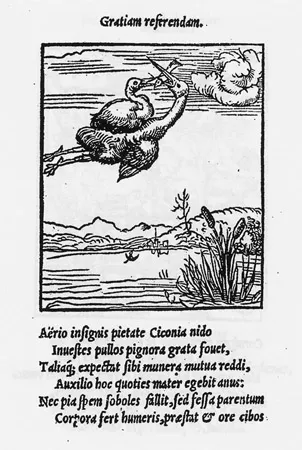

Autonomous editions of Alciato’s emblems presented from the start a three-part composition, consisting of a title or motto, an illustration, and an epigram, but editions contained within volumes of his Opera usually lack the illustrations. The format was not followed by all his imitators, some of whom omitted the title or motto, others the epigram. In the editions which do not have the format introduced by Aneau the emblems appear to follow no ordered sequence. Some, as we suggest ahead, are personal and occasional devices, some seem to have a topical political or satirical intention (the particular circumstances of some may now be unknown to us), and others propose moralizing interpretations of subjects drawn from mythology or natural history (Figs. 1.1 –1. 2). The epigrams vary considerably in length from one to sixteen distichs. What they do have in common is a description or at least an identification of the subject illustrated and an interpretation, though even here not always in that order, and occasionally emblems are found in which the name of the subject or the intended meaning is to be seen only in the title or motto. The symbolism, as explained ahead, seems to be consistently of a traditionally allegorical or metaphorical rather than a Neoplatonist nature.

How should one characterize Alciato’s emblems? Various approaches suggest themselves. One could ask about the provenance or source of the emblem. One might look at the application or interpretation of the emblem in the subscriptio. One could attempt to group emblems according to some larger topic, such as politics, religion, or ethics. One could consider the central motif, the object or event illustrated.

Figure 1.1 In nothos (Padua, Tozzi, 1621) 600. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

Source hunting is unlikely to account for the popularity of Alciato’s emblems, although questions of source and provenance may interest scholars. One possible source, however, is worth a

Figure 1.2 Gratiam referendam (Paris, Wechel, 1534) 9. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

comment. The scholars of the Renaissance wrongly believed that in the Hieroglypica Horapollinis they had discovered a key to the meaning of the ancient Egyptian signs inscribed on obelisks and other monuments, whereas the hieroglyphs were really a form of esoteric writing. These hieroglyphs flowed into the mainstream of the emblem both directly through the original Greek version of the Horapollo, first printed in 1505, and translated into Latin in 1517 (there were at least thirty subsequent editions12), and indirectly through medieval Christian allegory, the most important work of this kind being Physiologus, and through the books of “imprese.” One of the first literary works to use the hieroglyphs fairly systematically was Francesco Colonna’s richly illustrated Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, which probably dates back to the 1460s, although it was first published in 1499. Colonna’s hieroglyphs and their inscriptions were considered genuine, although in fact they were essentially recreations of his imagination, largely inspired by other imitations of hieroglyphs. Alciato certainly used some of the same hieroglyphs as this work, but it seems unlikely that he conceived of them as signs in the same way as Colonna.

Assuming that one opted for the application or interpretation, the “meaning” of an emblem, then the first task would be to assign such meaning to each and every emblem. But it is not always possible to equate one emblem with one topic, let alone one meaning. Should the motto always be regarded as providing the meaning, or direction of meaning? For instance, Alciato uses the emblem “Imparilitas” (Inequality) to rate Pindar above Bacchylides. Is this emblem then a form of literary criticism? Or should the emblem be considered a comment on the inequality of Alciato’s colleagues? It features four birds: the high flying falcon, and the jackdaw, goose, and duck that remain close to the earth. Alciato usually, but not always, identified the general topic of his emblem in the motto, but some mottoes, such as those of the tree emblems, merely name the object. Then again, Alciato’s epigrams occasionally present more than one application. For instance, the emblem “In facile a virtute desciscentes” (On those who easily fall from virtue) shows a small remora impeding the progress of a great ship. The epigram suggests that the image conveys three things: a petty cause, a lawsuit, and “passion for a harlot, which draws youths from outstanding studies.”

As first printed, Alciato’s emblem book was a more or less unorganized collection of self-contained statements on a variety of topics. Some editions, such as the French translation by Barthélemy Aneau (Lyon, 1549), regrouped the emblems in loci communes. But the new orderly arrangement is far from satisfactory. Why should “In silentium” be grouped under “Fides,” or “Garrulitas” under “Superbia,” or “In colores” under “Amor,” to take but three examples? But some early and later editions continued the original unorganized arrangement, notably those of Jean de Tournes and those containing the French translation of Jean le Fèvre. Alciato’s emblems do, however, provide evidence of ethical, social, political, and religious principles, and occasionally of economic concerns.

The emblems of the originator of the new genre cover a wide spectrum of characteristic humanistic concerns. Without prioritizing the themes, it seems clear that Alciato’s overriding concerns may be labeled moral, rather than moralistic, and ethical in the broadest sense. “Moral” here includes traditional notions of good and evil, with the virtues and vices taking an important place. Then there are professional concerns with justice and education, the former perhaps inevitable for a lawyer. Political topics are more widespread than a casual re...