eBook - ePub

Responses to Disasters and Climate Change

Understanding Vulnerability and Fostering Resilience

This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Responses to Disasters and Climate Change

Understanding Vulnerability and Fostering Resilience

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As the global climate shifts, communities are faced with a myriad of mitigation and adaptation challenges. These highlight the political, cultural, economic, social, and physical vulnerability of social groups, communities, families, and individuals. They also foster resilience and creative responses. Research in hazard management, humanitarian response, food security programming, and other areas seeks to identify and understand factors that create vulnerability and strategies that enhance resilience at all levels of social organization. This book uses case studies from around the globe to demonstrate ways that communities have fostered resilience to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Responses to Disasters and Climate Change by Michele Companion,Miriam S. Chaiken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Derecho & Ciencias forenses. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section I

Methodology, Policy, and Early Warning Systems

Methodological Strategies and Early Warning Systems

Chapters in this section highlight the need for deeper collaboration with and input from local stakeholder communities. These chapters reveal the barrier often created between “experts” and the local communities, where academic knowledge and pedigree or governmental status become elevated over lived experience and traditional observations. Cultural sensitivity necessitates incorporation of a broader array of voices, such as marginalized and indigenous people, into all planning, mitigation, and response discussion. This ensures the building of effective and collaborative communication structures and provides opportunities for creative programming and thinking outside the “expert” box.

1 | Vulnerability and Resilience to Climate Change in a Rural Coastal Community |

CONTENTS

Introduction

Deal Island Peninsula Vulnerability to Climate Change

Expected Environmental Change

The Deal Island Marsh and Community Project

A Socioecological Systems Framework

Collaborative Learning

Network of Stakeholders

Collaborative Science Approach

Results: A More Nuanced Understanding of Vulnerability and Resilience

Lessons Learned and Conclusions

References

Abstract

The Deal Island Marsh and Community Project is an ongoing collaborative effort among scientists, environmental managers, and local community members to improve resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate change impacts in a coastal socioecological system. Using the toolkit of collaborative learning, which relies upon adult and experiential education, conflict resolution, and systems thinking (Feurt 2008), we are building a stakeholder network to engage participants. Alongside experiential and collaborative activities, formal research and data collection produces knowledge from across the socioecological system that can be used to inform environmental management strategies, further research interests, and share with local community members. Knowledge and social ties built through our network are integral to complex and lively understandings of vulnerability and resilience and determining their leverage points. This chapter discusses four strategies that help us understand ecological and community vulnerability and potential resiliencies while maintaining a systems perspective. These tools and methods can provide best practices and inform work elsewhere.

INTRODUCTION

Producing resilience to climate change impacts among communities is important, but multiple challenges impede these efforts. In academic and practitioner arenas, differences in disciplinary commitments and theoretical approaches can hamper collaboration. For instance, integrating social and natural science research and data can be problematic. Ideological divides can also undermine progress. This is particularly true when cultural norms lead people to distrust key findings of climate science. Perhaps most critical is a lack of long-lasting partnerships bridging institutional and organizational boundaries to address community and ecological vulnerability. These challenges are overcome by linking vulnerability and resilience to climate adaptation planning using strategies for systems thinking and collaboration.

The Deal Island Marsh and Community Project (DI Project) is an effort to build resilience to climate change in a rural coastal community. A collaborative stakeholder network and research are key project outputs. In particular, findings relate to vulnerabilities and resiliencies for the socio-ecological system and inform adaptation planning. Resilience is often positioned as a positive and relational attribute of a system: “the ability to cope with shocks and keep functioning in much the same kind of way” (Walker and Salt 2012, p. 3). Vulnerability, correspondingly, is a negative system attribute: “[the] degree to which a system is likely to experience harm owing to exposure and sensitivity to a specified hazard or stress and its adaptive capacity to respond to that stress” (Chapin et al. 2009, p. 241). Vulnerability and resilience are best considered together to understand complex relationships related both to impacts and efforts to recover from disturbance events.

The impact of environmental and physical change on communities is a product of social and relational features influencing vulnerability and resilience for an area. For example, residents of low-lying areas may not agree that sea-level rise is a significant threat because they have more immediate and pressing concerns. Consensus in definitions of vulnerability and resilience cannot be assumed. The DI Project is a model for connecting climate change research and a community of stakeholders to develop solutions to problems in unique ways.

DEAL ISLAND PENINSULA VULNERABILITY TO CLIMATE CHANGE

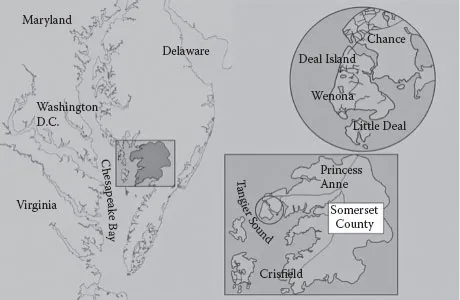

The Chesapeake Bay is the United States’ largest estuary and a site of contentious resource regulation and increasingly strict environmental management for conservation and pollution reduction (Chesapeake Bay Program 2014; Ernst 2010). The Deal Island “peninsula” is 18 square miles of landscape and islands dominated by marsh, tidal waterways, and forests, interspersed with agricultural and residential land use along the Maryland shorelines of the Bay (Figure 1.1). One main road traverses marsh, creek, and open water to connect several small and unincorporated hamlets across flat coastal plain with an average elevation of only 3 feet. Long-time community members distrust outsiders and government involvement. This has escalated with management of fisheries and marshlands; many feel the government unfairly burdens them with regulation. As climate change adaptation proceeds, the community position should be acknowledged. They can be both marginalized and, at the same time, central to contestations over environmental management (Paolisso 2005).

FIGURE 1.1 Deal Island Peninsula, Somerset County, Maryland, is adjacent to the Tangier Sound of the Chesapeake Bay. (Courtesy of http://iStock.com/crossroadscreative and Maryland Sea Grant.)

Bay livelihoods have changed with increased development and the decline of water-based economies. Many rural communities have disappeared due to out-migration, economic decline, or encroachment of Chesapeake waters (Cronin 2005; Erwin, Brinker, Watts, Constanzo, and Morton 2010; Leatherman, Chalfont, Pendleton, McCandless, and Funderburk 1995). Some, like those in the Deal Island peninsula area, have maintained vibrant communities despite population decline and an aging population. Today, about 1000 people are dispersed between historical inland communities and private waterfront homes developed by vacationers and retirees (American Fact Finder 2013). Two small convenience stores (one selling gas) are available for food and amenities, but many more existed in the area’s heyday of seafood harvesting and processing industries, regular steamboat commerce, and United Methodist Church revivals and camp meetings (Rhodes 2007; Roberts 1905; Wallace 1978).

Watermen (commercial fishermen) still catch crabs, oysters, and fish year-round. Hard working and independent, watermen provide a cultural and economic backbone for the community despite their dwindling numbers. Heritage is an ongoing and lived experience for peninsula residents, linking past to present on a daily basis (Paolisso 2002 and 2003; Power and Paolisso 2007). When you ask someone what is special about the area, they talk about faith, family, quietness, and the community’s commitment to a slower pace of life. During semistructured interviews conducted with 25 DI Project stakeholders in spring 2014, many local community members indicated that they identify so strongly with the area that they couldn’t imagine living anywhere else.

EXPECTED ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

The region’s relative sea level has increased 30 centimeters over the last century (Titus and Strange 2008). It is predicted to rise another 110 centimeters within the next century (Boesch et al. 2013), increasing flooding, storm surge, wave height, and tidal flows (Spanger-Siegfried, Fitzpatrick, and Dahl 2014). Geologically induced land subsidence has been measured at 5 millimeters per year in the Chesapeake region (Eggleston and Pope 2013), while the peninsula’s rates of erosion are significantly greater than Maryland’s average (Maryland Department of Natural Resources [MDDNR] 2008). Anticipated impacts also include temperature fluctuations, changes in rainfall, increased storm frequency and severity, and salinity intrusion, all with profound effects on landscape and hydrology (Najjar et al. 2010).

Brackish marshes are a prominent feature of the area’s landscape and provide habitat for important species (Scott 1991). The marshes are managed by MDDNR to promote fish spawning, wildfowl hunting, and mosquito reduction. Along the Atlantic seaboard, coastal marshes are declining rapidly due to sea-level rise and other environmental stressors with dramatic consequences for coastal ecosystems and local communities (Needelman 2012). Land subsidence and anthropogenic disturbance, particularly extensive ditching in the early 20th century, have compromised the natural ability of marsh to accrete. As sea levels rise, marsh erosion and submergence will impede storm surge mitigation and other socioecological services. Local communities seek cost-efficient restoration and conservation approaches to increase resilience in marshes and communities in the face of these impacts.

THE DEAL ISLAND MARSH AND COMMUNITY PROJECT

The DI Project (www.dealislandmarshandcommunityproject.org) was originally funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Estuarine Research Reserve Science Collaborative Program (Fall 2012–Summer 2015) and has received additional support from the University of Maryland’s College of Behavioral and Social Sciences and College of Agriculture and Natural Resource, MDDNR Chesapeake and Coastal Service, and the US Geological Survey Water Resources Research Program. The project is managed by Drs. Needelman and Paolisso, in partnership with representatives from MDDNR. Significant involvement by local organizations and churches has helped to extend project leadership into the local community. Paolisso has been working as an environmental anthropologist in the area for over 15 years; he was integral to engaging local community members.

The DI Project is an ongoing collaborative effort among social and natural scientists, environmental managers, and local community members. The project improves resilience and reduces vulnerability to climate change impacts across the socioecological system using several objectives to restore and conserve marshes and local communities. This includes establishing collaboration among stakeholders, developing and testing a broadly transferable process of engagement, and producing a better understanding of socioecological services by marsh systems and decision-making processes within the stakeholder community using integrated anthropological, economic, and ecological applied science.

Four key strategies have enabled success toward objectives and promoted development of a more nuanced understanding of ecological and community vulnerabilities and resiliencies. These include the conceptualization of vulnerability and resilience as part of a socioecological system, the implementation of collaborative learning to deepen insight, trust, and sharing among project participants, and the creation of a network of stakeholders to diversify views and skills available to address issues. Finally, there is the use of collaborative science, which brings an interdisciplinary perspective.

A SOCIOECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS FRAMEWORK

Resilience researchers (Adger 2000; Folke 2006) highlight the importance of socioecological systems frameworks. Using “systems thinking” emphasizes holistic and complex perspectives, giving equal footing to environmental and social concerns. The DI Project’s framework is similar to the “situated resilience approach” described by Cote and Nightingale (2012), prioritizing institutional and functional configurations in the socioecological system and also “processes and relations” supporting the system (p. 480). This framework allows exploration of system features, dynamics and feedbacks between those features, supporting institutions and arrangements, and the relationships and perspectives of network stakeholders that contribute to climate change resilience.

As Nelson, Adger, and Brown (2007) argue, defining resilience in a systems context increases understanding of vulnerability and adaptation in three ways. First, more sociocultural factors are included. These reveal tensions in environmental and social relations and identify vulnerabilities that can be historically or politically constructed. This includes a focus on vuln...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Editors

- Contributors

- Introduction

- SECTION I Methodology, Policy, and Early Warning Systems

- SECTION II Impacts on Resilience and Vulnerability

- SECTION III Community-Based Factors That Impact Resilience and Vulnerability

- Index