eBook - ePub

The Velvet Revolution at Work

The Rise of Employee Engagement, the Fall of Command and Control

This is a test

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Velvet Revolution at Work

The Rise of Employee Engagement, the Fall of Command and Control

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

What drives or delivers engaged people? Employers need to focus on creating the right conditions. Employers can't impose engagement: people need to choose to engage themselves. In The Velvet Revolution at Work, the follow-up to his best-selling The CEO: Chief Engagement Officer, John Smythe explains that the essential ingredient of the right conditions is a culture of distributed leadership which enables people at work to liberate their creativity to deliver surprisingly good results for their institution and themselves. Using models, examples and anecdotes from his client research he goes on to demonstrate exactly how to design an engagement process; one that is integrated with your business strategy and that is sustainable.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Velvet Revolution at Work by John Smythe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART I

What is the Velvet Revolution at Work?

1

The Velvet Revolution at Work – Why Now?

In the Introduction, I suggested that in addition to a sound business case, social forces would stimulate the emergence of the employee engagement movement.

Looking back at the history of work in the UK since the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is punctuated by major events such as the migration from the land to the city, the rise of union power to counteract the power of capital, the decline of union power, nationalizations and privatizations, the influence of various management theories and the rise of entrepreneurship.

The leader and employee engagement movement – E theory – may be a defining shift in the way we work, but it is not new.

Employee Engagement is as Old as the Hills

Employee engagement is as old as the hills in the sense that leaders have been practising it ever since mankind emerged as a collaborative social group. Leaders have been making informed judgments about what they alone will decide versus which individuals or groups will add value to decisions on the basis of the specialist knowledge and experience those groups have or because of the power that they hold. The key phrase is ‘making informed judgments’.

When I worked on a study with McKinsey & Company in 2004 called ‘Boot Camp or Commune’ (one of the first studies to look at this topic), we found that nearly every CEO we interviewed made instinctive, automatic and thus irrational judgments about engaging people in decision making. Questions about their thought process about approaches to employee engagement were met with naiveté and the disclosure that consideration of it was typically not part of their decision-making process. This was in contrast to their approach to strategy (or content) formulation, which they reported as being thought through in a more considered way either alone or with a range of people enfranchised for political and quality purposes. In other words, their approach to engaging their people usually attracted little or no thought at all, with the result that ‘decide and tell or decide and sell’ approaches to strategy origination and execution were the dominant method of decision making.

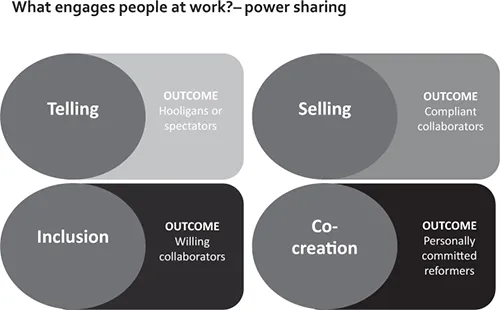

Figure 1.1 below represents four approaches to decision making and engagement.

The conclusion from that 2004 study was that leaders should make conscious and visible decisions about which approach, in terms of engaging their populations, will add value. By value I mean the quality of decisions and the broad ownership of them by those who must deliver.

Figure 1.1 The four approaches to decision making and engagement

In a traditional command and control environment, an elite concludes the thinking about the content (the what) and the execution (the how), and then casts about for ways to tell its people what has been decided. This linear approach to decision making inevitably results in a ‘tell or sell’ mode of engagement which casts recipients as spectators of the process, however apparently engaging or entertaining the communication is. This is a value-destroying approach to decision making, as most of the population have not been invited to challenge and contribute, and thus the outcome is representative of a tiny minority of the collective memory and expertise of the enterprise, added to which those who are relied on to execute a top-down decision feel little ownership of it and are not readily motivated to help.

Under command and control, ‘decide and tell and decide and sell’ are the default engagement approaches. When people are precluded from challenging and contributing, often through ignorance by leaders of the choices available to them to engage people, it is little wonder that so many organizational initiatives come and go with little impact.

A command and control culture is exposed by its language. Metaphors of the military and religious abound – briefing, front line, vision, mission, mobilize, align, morning prayers and so on. Command and control served well as the postmodern foundation for large, multi-location organizations where it was thought that tight control was the best and only way of standardizing production methods and customer experience.

Whilst there are now many instances and examples of more inclusive and ‘engaging’ styles of leadership, command and control, in one guise or another, is still the dominant experience for many people at work. Of course, there are many highly successful organizations which seem to thrive on command and control and there may be so for a long time to come.

The Birth of an Alternative to Command and Control

However, we may be at the birth of what is an evolution to the next style of leadership at every level in organizations. This is a protracted birth which will be characterized by as many ups and downs as the Velvet Revolutions that took place across Eastern Europe and now in the Arab world. Peter Drucker's early calls for more inclusive leadership may at last have found their time. What follows is my view of what UK social history has to tell us about the deal between employers and employees. Your country's history and culture will also have a significant bearing on the deal between employees and employers.

I am no historian, but drawing on the accounts of others, it is worth remembering that the history of organized industrial work with massed workforces is barely 250 years old, dating back to the late 1700s. The UK as the cradle of the first Industrial Revolution was the first mover in learning to manage and organize large numbers of workers. If we take a walk back in time in the UK, what do we find?

Among the first vivid images of people at work are the sweat shops of Victorian England brought to us by the paintings of L.S. Lowry or the writing of Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell. Fast forward to today and these working conditions can still be found in many parts of the world. In the UK people had migrated from the privations of the land to squalor in crowded slums where they found themselves to be the human cogs in the industrial machine. The first capitalist robber barons in the UK and the USA experienced little pressure in the early days of industrialization from the disenfranchised and unrepresented masses for better conditions.

However, amid the gloom emerged social thinkers like Robert Owen writing in the early nineteenth century (Selected Works of Robert Owen, William Pickering 1930) and industrialists that brought us Port Sunlight and Bourneville as examples of model industrial towns where workers received a better deal. These individuals were among the first advocates of worker mutuality and engagement.

In the USA, Andrew Carnegie epitomized the idea of social responsibility articulated in his Gospel of Wealth (North American Review, June 1889). He said that ‘Happier, warmer and healthier’ workers produced better results. It was self-interested care, but it was a deal that he claimed was more sustainable than one-sided capitalism. These ‘social industrialists’ were rewarded with better outcomes and recognition for the way they balanced the needs of workers and capital more equitably.

Soon enough, the benefits of mass output started to benefit the workers and the early seeds of the consumer were planted – after all, without consumption, there is a limit on returns. Consumerism was ultimately to become a brakeon capital in the sense that, without consumer support and demand, profit is limited.

Today this extends to consumers switching away from brands they consider to be misaligned with their own values. Thus, exploiters of child labour have been forced to manufacture with the supply community in mind as well as the consumer. And in the UK in late 2012 the reported underpayment of tax by global businesses resulted in some consumers shunning these companies.

The Engineering Strike in Yarrow Shipyard, Southampton (1897)

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the struggle between capital and labour spawned the emergence of the union movement which, in its first guise, can take credit for attempting to balance the books in favour of the worker.

The tussle between profit and people included violence. In the USA workers routinely found themselves being policed and killed by fellow workers wearing, among others, the uniform of Pinkerton's private security guards. In the 1877 strike against the Baltimore and Ohio (rail) company, President Rutherford Hayes sent federal troops to quell rioters, who themselves were armed to the teeth under the US Constitution's right to bear arms (see Richard Donkin, The History of Work (2010)).

In academia, early theories framed work as a rational machine (Taylorism, Principles of Scientific Management (1911)) with workers taking their place as a coerced cog. Taylorism had admirers like Henry Ford and other early proponents of rigidly enforced standardization in which initiative was expressly forbidden.

Taylorism was later characterized as X theory by Douglas McGregor, who countered it with Y (The Human Side of Enterprise (1960)) theory that posited that high performance was an outcome of trust and the granting of initiative to workers which drew from Japanese success in driving up quality through collaborative teamwork as demonstrated by Volvo's early successful application to its team-based approach to manufacturing.

The Rise of the State

The periods following the Second World War in the UK witnessed the rise of the state and a rise in the number of state workers. At that time, to be a high-flying civil servant was a glittering career path and many employees in the private and public sectors enjoyed a cradle-to-grave employment promise. To this day, in the UK the state sector is a well-preserved example of the command and control work place culture. Whilst the rhetoric in the UK state sector may be ‘the new model workplace’, the reality is a persistent devotion to hierarchy, bureaucracy, protocol, deference and risk aversion.

The rise of the state matters because when it becomes the main employer, as the DNA of work becomes overshadowed by the values and mores of the state institution. In Scotland today the percentage of GDP generated and consumed by the state is around 73%. In Wales and Northern Ireland it is above 60% and is rising. In the south-east of the UK the percentage of GDP deriving from the state sector is 25% and less in Greater London, the engine of Britain (BBC). Following the Second World War, the private sector mirrored the state sector in adopting the leadership model of command and control. People would aim to join and stay with a company or public sector institution for their working life and, by offering their loyalty, would be rewarded with certainty, perks and development.

The deal started to break down as the last millennia came to an end and companies and institutions started to scale back their side of the bargain. The decline of final pension schemes and their generous index linked payouts for life was a major cause of this breakdown. Meanwhile, internal communication in its first guis...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Introducton

- PART I: WHAT IS THE VELVET REVOLUTION AT WORK?

- PART II: STRATEGY THROUGH PEOPLE: DELIVERING STRATEGY AND CHANGE THROUGH PARTICIPATIVE INTERVENTIONS THAT ENGAGE THE RIGHT PEOPLE

- PART III: BEYOND THE INTERVENTION: THE ENGAGED ORGANIZATION

- References

- Index