![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

GEOFFREY MITCHELL

Overview

Death will come to us all - for some quickly, and for others over weeks, months or years. Where the latter course occurs, the final stages of life are a time of declining physical capacity and increasing reliance on others. Increasing symptoms, physical dependence, and uncertainty about their personal future and that of their loved ones are some aspects of a fearsome and sometimes dark journey.

The care of palliative care patients encapsulates all facets of good family practice: if a doctor does family practice well, he or she will do palliative care well. However, while palliative care can be relatively straightforward, problems can arise that are beyond the skill of a generalist. Now that palliative care specialist teams exist there is backup advice and support for most family practitioners. But having specialist teams available in most locations is not a reason to cede all palliative care to them. Too many people die, and specialist teams cannot cope with them all. It is in everyone’s interest for family practitioners to be competent in this area.

Death is unfamiliar territory for many in the Western world. Not many people have seen a dead person or watched someone die. When dying does occur, it occurs outside the context of the person’s normal life - frequently in hospitals or other care facilities.

In the middle part of the 20th century death was seen as medical failure. Spectacular medical and social advances had robbed formerly killer diseases of their potency, and most people started living to old age. When treatments failed to arrest the progress of diseases, health practitioners found they did not have the wherewithal to manage a patient’s death. In the last days, dying patients would be placed in a single room, sometimes not even visited by healthcare staff. It was as if the health profession could not face the fact that they could not control the disease, so it was best not acknowledged at all. Needless to say, symptom control was poor, and the physical suffering that many endured reinforced the mood of the day - that dying was repulsive and death was to be feared.

A paradigm shift occurred in the 1960s, which swung the pendulum away from complete dependence on high-technology medicine towards a more integrated approach. In a general sense this movement began when Ralph Nader challenged consumers to ask questions about the goods and services they received, rather than simply assume that the providers knew best. With respect to dying, twin influences arose through two remarkable women studying dying patients from diverse points of view. A young Cicely Saunders commenced work as a nurse, then social worker, then finally as a doctor. She was the first to study the process of dying systematically - in particular, the management of pain in dying people. In time she developed a completely new institution to care for dying people and to provide an environment where scientific study of the process could be carried out. From that beginning in 1966 has grown a new medical specialty, palliative medicine. At around the same time, sociologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross deliberately studied the experiences of dying patients. Her seminal book, On Death and Dying,1 forced society to look at how it understood death, and how it should understand the experience of, and relate to, the dying.

Out of these advances has arisen the palliative care movement. It is no accident that palliative care is frequently described as a movement. At the time it was both a medical advance and a social advance. It was led by lay people questioning healthcare and in particular the care of dying people. At the same time, doctors and academics willing to question the status quo put enormous effort into providing a scientific basis to end-of-life care. The result has been the global development of a new way of providing care for the dying - palliative care. The World Health Organization’s definition of palliative care highlights the rigour that the discipline of palliative care should demonstrate, while promoting the expectation that healthcare will create an environment and systems that pay homage to the innate human experience that is dying.

A quiet revolution also took place in family practice (also known as general practice or primary healthcare in different parts of the world) at around the same time. Michael Balint used psychotherapeutic supervision of British GPs to create a better understanding of the profound impact the relationship between doctor and patient has on patient outcomes.2 He termed this phenomenon ‘doctor as drug’ to highlight the power of this effect.

In-depth study of the power of the family practice consultation enlarged our understanding of how this power can be harnessed to the benefit of the patient. Concepts like Pendleton et al.’s ‘Tasks of the consultation’, a term coined in the 1980s, now drive clinical family practice by introducing the concept that satisfactory outcomes for a consultation require a multifaceted approach.3

Stewart et al. have brought all these strands together in what they term the ‘patient-centered clinical method’.4 Where Pendleton et al.’s model is somewhat doctor-centered (i.e. what the doctor should achieve in the consultation), Stewart and co-authors place the patient at the center of their model, requiring the doctor to apply their knowledge of a disease process to the patient, and to pay attention to the many facets of the patient’s experience and that of those around them.

What is the patient-centered clinical method?

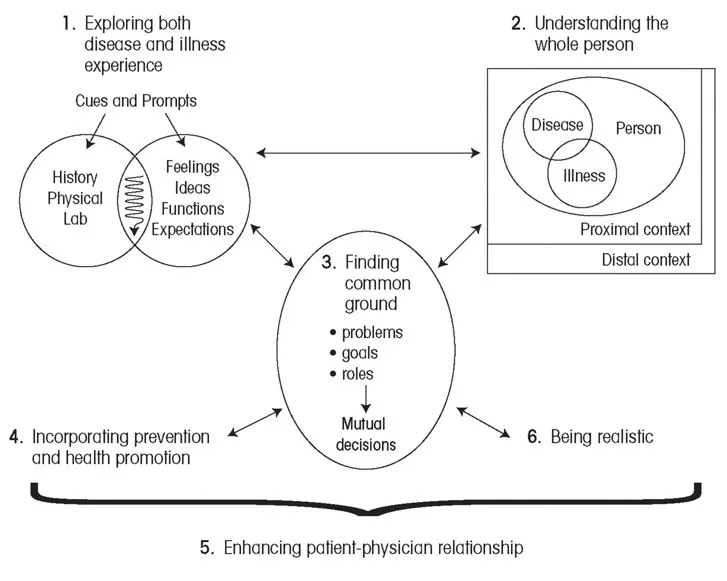

Figure 1 pictorially represents the patient-centered method of clinical practice.

The method consists of six interactive components.

1. Initially the disease is considered, but at the same time the patient’s experience of being ill with the disease has to be explored. The two are inextricably interwoven and therefore have to be understood as a single entity comprising related paradigms.

2. Understanding the whole person is the component that seeks to place the disease/illness entity into context; that is, to understand its place in the whole person. This means giving consideration to three questions:

How does the disease/illness entity affect the person?

How does the person interact with those elements of their immediate environment, and vice versa? Immediate environment is described as

proximal context, and includes those parts of the environment with which the person has regular, close contact. This includes their family, work, school and other close social networks.

How does the wider environment influence this interaction? The wider environment will include community, culture, health and political systems, socio-historical systems, geography, the media, the environment, and so on. This is termed the

distal context.

3. The third component of the patient-centered method is termed finding common ground. Patient and clinician reach a mutual understanding and agreement on the nature of the problems, the goals of management, and who will be responsible for what.

The final three parts of the model relate to strategies and understanding of the patient-doctor relationship that will improve the performance of the whole system.

4. The first is the desirability of undertaking broader health-promoting and illness-prevention tasks within the consultation. Most patients visit a GP or family practitioner at least once a year. These doctors have unparalleled opportunities to influence the health-enhancing behavior of that individual.

5. The second is to have an understanding of the patient-doctor relationship in order to enhance it. It is a relationship that should be valued greatly by practitioners, and an understanding of the investment that patients put into this relationship should make doctors very mindful of the way they exercise their part in it. Their use of the relationship can enhance the power of the consultation for everyone’s good, but it can also do irreparable harm.

6. Finally, the practitioner needs to assess what can be realistically achieved to assist the patient. Practical limits to the time and skills of the practitioner need to be acknowledged by both patient and practitioner. The possibilities of enhancing the power of the health encounter through working in teams need to be recognized and, if possible, implemented. The wise stewardship of resources also needs to be taken into account.

Each of these elements of the patient-centered model is examined in detail in its own chapter.

FIGURE 1 The patient-centered clinical method: six interactive components

The aims of this book

This book applies the patient-centered method to the practice of palliative care. There are significant overlaps between palliative care and family or general practice. Both are centered on the patient, and both recognize the essence of a multidisciplinary or multifaceted approach to patient care. Both expect high-quality, evidence-based approaches to care, and both disciplines are currently working hard to accumulate that evidence. Finally, most of palliative care will be conducted in the community, with family or GPs undertaking a large share of the medical care of the patient and the family.

This book brings a fresh perspective to the subject by presenting it through a patient-centered lens. It presents a model and a method of care, but not every nuance of the subject. World experts in their fields examine palliative care from points of view as diverse as epidemiology, palliative medicine, nursing, behavioral science, sociology and health promotion. The model and method bring these points of view together. Books that present in-depth material on medical techniques, drug doses and the like are freely available. This sort of information is described briefly in the text, but the detail can be easily sourced elsewhere.

We hope this will be an important resource for clinicians and educators in the medical, nursing and allied health professions. It provides valuable information for policy-makers and administrators by presenting an intellectual framework within which patient care policy and procedures can be formulated and enacted. We trust you will enjoy the book, and will find ways in your own practice to use the patient-centered clinical method to enhance the care of your patients.

References

1 Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. London: Tavistock; 1970.

2 Balint M. The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness. New York: International Universities Press; 1972.

3 Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, et al. The Consultation: an approach to learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1984.

4 Stewart MA, Brown JB, Weston WW, et al. Patient-centered Medicine: transforming the clinical method. 2nd ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical; 2003.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Palliative care: the magnitude of the problem

JONATHAN KOFFMAN, RICHARD HARDING, IRENE HIGGINSON

Introduction: the universal right to care at the end of life

We emerge deserving of little credit; we who are capable of ignoring the conditions that make muted people suffer. The dissatisfied dead cannot noise abroad the negligence they have experienced.1

Nearly 40 years ago in this sta...