This chapter explores how we use models and metaphors to make sense of the world and act. It sets complexity in the evolving story of scientific thinking, from modern science, that traces its origins to the time of the enlightenment, through post-modernism to complexity science.

Key points

Models create reality around bundles of related assumptions that help us make sense of the world and act.

The use of metaphor offers insights that can be lost when we construct models.

Models and metaphors are consolidated into disciplinary frameworks known as paradigms. Paradigms can exert a deep hold on how we view the world.

Despite many successes, the paradigm of modern science has been limited in its ability to predict and control the behaviour of human organizations.

Complexity science is the study of dynamic, non-linear systems. The model is a network of co-evolving elements where changes in one element can change the context for all other elements. This has profound implications for how we view organizations.

The metaphor for understanding organizations changes from machine to ecosystem.

Complexity aims to complement modern science, not overturn it.

Making sense of the world using models

As humans we have a recollection of the past and an anticipation of the future. Sense making allows us to make the connection and act. To do so we simplify the world by constructing models, creating reality around ‘bundles of related assumptions’. We look for patterns in our experience while classifying them into categories. We also look for patterns in the interactions between categories, searching for relationships and regularities.1 Philosophers struggle to reconcile what’s out there with our internal representations without agreement - models are always approximations of the real world. Models help us to address two questions:

the descriptive element - what is happening, what will happen?

the prescriptive element - how can we make what we want happen?

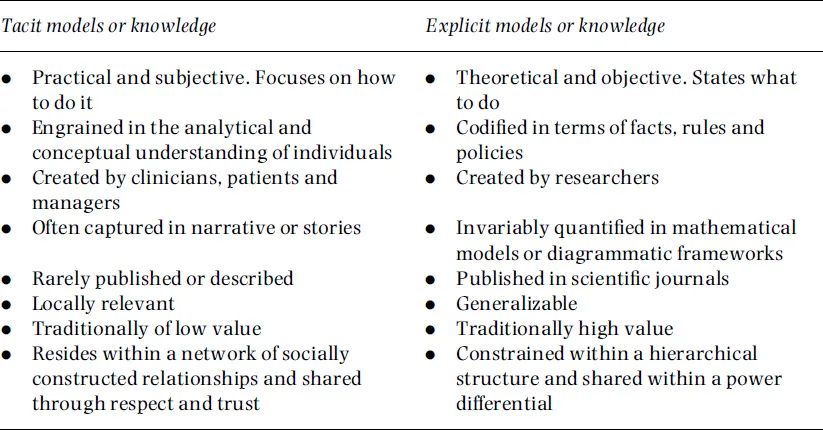

Our models powerfully influence how evidence is collected, analysed and understood. At an individual level, we create tacit models or knowledge by reflecting on our experience and comparing it with our expectations, continually rethinking our ideas on causation and intervention. We operate according to these internal mental models that are often below the level of consciousness. They represent the rules for how we order and categorize information and how we respond to our environment. They form our knowledge - how we process and act upon information presented to us. For example, practitioners usually know more than they can say. They reveal a capacity for reflection on intuitive knowledge in the midst of action and use this tacit capacity to cope with the unique uncertain and conflicting situations of practice.2 However, when models are implicit, their potential to confuse or obscure new insights can go unnoticed.

Models can also be explicit and shared. Knowledge management is currently an important concept in organizational theory and a recurring theme in this book within the context of ‘learning organizations’. The contention is that individual knowledge is largely unknown to others and therefore wasted. The aim is to capture and share this knowledge for the benefit of the whole organization.

Table 1.1 shows some differences between tacit and explicit models or knowledge.

Table 1.1 Some characteristics of tacit and explicit models or knowledge

In organizations, our shared models are constructed and maintained in symbols that we offer each other. These symbols can be artifactual (for example, organization strategies, documents, uniforms) or communicative, mainly through the use of language. We also design spaces for the creation of our ideas. These symbols and the design of spaces for the creation and interchange of our symbols not only allow us to explore our organizational possibilities but also to place boundaries on them. However, we need to be aware that different organizational cultures may have differing symbolic interpretations. Within organizational contexts, we might also anticipate dysfunctional consequences when there is a dissonance between future expectations derived from our own sense-making models and expectations imposed upon us within a bureaucratic structure derived from different models.

Models need to have external consistency (i.e. they have predictive value) and internal consistency (i.e. they are compatible with other models). Studies in stroke victims suggest that model making is reflected in brain architecture. The left hemisphere creates a model that it maintains at all costs whereas the right hemisphere detects anomalies and forces the left hemisphere to revise it, maintaining internal consistency.3

One way we test and share our models is through the use of narrative or storytelling.* We create our realities with the same motives, themes and structure as fiction. Our culture binds us by a set of connecting stories.4 Perhaps through storytelling we modulate the creative tension between our right and left brains as our models are formed and reformed.

Making sense of the world using metaphor

Because models simplify reality they often lose intuitive insights and the use of metaphor helps to retain this information. Metaphor brings together two areas of experience, treating one as if it had the features of the other applied to it. Metaphor can organize our patterns of thinking as we both reflect and interact with each other, helping us to grasp reality in clearer terms. It offers a framework to think and act differently. Aristotle wrote: ‘ordinary words convey what we know already; it is from metaphor that we can get hold of something fresh.’

For example, sense making has been described in terms of the metaphor of cartography.5 There is no one best map of any particular terrain - the ground is not already mapped. What sort of map is made depends on where cartographers look, how they look and what tools they have for representation. Map making tends to be social - we construct our maps through our relationships with others through the use of symbolic communication.

How we understand and behave in our organizations is reflected in the metaphors we use to describe them. For example, Morgan6 offers a range of metaphorical interpretations ranging from machines to organisms, from brains to psychic prisons. However, metaphor has the potential to mislead if applied inappropriately as the following example demonstrates.

In 1998, in response to disappointing waiting-list statistics, the Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, stated: ‘I said...