SECTION 1

Decision making and the big picture: making sense of health service delivery

Tom Cartmel, a nursing professor, was taking a sabbatical year in the Netherlands. During this period he struck up a correspondence with Marie, one of his former students. Her recent clinical appointment and associated professional studies had opened up new lines of enquiry, particularly about health service delivery and decision making. His initial reply (that subsequently developed into a regular correspondence) focused on the relationship between people at the heart of health service management. He continued….

Letter 1: The Main Focus

IMAGE 1 At an office in the Netherlands

Dear Marie,

Thank you for your recent letter. It was good to hear how you are progressing in your new clinical role, and how this has spurred you onto consider wider aspects of health service delivery and related decision making.

As you are well aware, to participate in health service delivery is to move into a complex world where even the briefest of clinical interactions is the collision of two distinct worlds. One is a professional world employing particular knowledge and skills applied to assessment, planning, intervention and evaluation. The other is the service user’s (or patient’s) world. Each world shares common human spiritual, physical, social and psychological characteristics.

At their intersection the participants bring something unique to clinical decision making. One observes, listens and even empathises whilst considering the clinical action to recommend and pursue. The other’s experience of their own stable, improving or failing health status shapes their negotiation and accommodation of the professional’s perspective. The dynamic of this relationship shapes mutual understanding and impacts on any decisions made. Many factors influence a professional’s decision making, including practice standards, professional conduct, political healthcare policies, legal boundaries, economic constraints, employment obligations and peer review. These frame the professional’s world-view, whereas the patient may hold a different world-view (and associated different health beliefs) that forms their interpretive framework to make sense of their situation. This interpretive framework can be a construct of individual values, beliefs, knowledge (that might challenge some assumptions underpinning the nature of professional knowledge) and notions of autonomy. Each interaction is unique, as is the relative importance afforded to different contextual factors such as beliefs, cultural practices, gender, education and language together with social and economic differences. Whilst at the moment I’m only considering the interaction between two people, between two worlds wider contexts need to be acknowledged. These include the setting (perhaps a clinic, a walk-in centre, hospital, a refugee camp, field hospital or the individual’s home), and socio-political (a particular society, government and laws), geographical, regional and international (for example the European Union) contexts.

Thus, the briefest of professional-patient interactions occurs within a series of bounding contexts that shape the way in which it is played out. It follows that within this commonality there is a unique individual characteristic to healthcare provision - it is not amenable to a ‘one size fits all’ approach. However, when considering health service delivery we are immediately challenged with a tension between providing services for many whilst ensuring these are tailored to the needs of the individual. When this emphasis moves towards a service for many it can render the individual as an object to be processed. You will be familiar with often heard descriptions like ‘another hip replacement’, an ‘elective surgical case’ the ‘appendicectomy in bed three’. This is no more than the patient seen as an object and indicates a shift has occurred from a person- to process-centred approach to healthcare delivery.

The challenge is clear Marie: we want to promote health service delivery focused on individuals, not categories or cases. The tensions inherent in managing, balancing and resolving multiple pressures and responses to short-term issues of the day can deflect from this focus. Thus, the decisions that you will make as a health service worker or manager will have to recognise the pervading complexity but preserve a service-user focus.

(In her letter Marie had hinted that the halcyon days as a student with limited clinical accountability and responsibility were long gone. Now she was moving on from the basics of professional practice to a greater involvement in care management. Professor Cartmel considered her question: ‘How do I make sense of this in an understandable way? Where do I start?’) He took up this question…

Marie, if we can agree on the focus of service provision we are ready to understand how a complex service can be arrayed around a service user.

(Cartmel had some suggestions to guide her knowledge and experience development pathway. He knew that the analogy of an iceberg was relevant to understanding how some staff perceived health service delivery. They only saw a fraction of it from their location, namely the ice protruding above the water’s surface whilst remaining largely unaware of the extent of submerged berg.)

If we apply an iceberg analogy to service design in which most of the berg or service is unseen, those who only make decisions on what is seen have a limited appreciation of how the system operates. Working with what is seen rather than including the unseen generates a knowledge gap that renders them ‘organisationally blind’ - we need to see the whole. This conveniently returns to my opening sentences about the context of the intersection of distinct professional and service-user worlds - it would be a useful step to examine and explain the organisational structure of your service as a whole so as to appreciate the immediate context of your decision making.

Kind regards,

Yours,

Cartmel

Coffee break: organisational design

Spend some time exploring and reflecting on the design of your local organisation.

Examine and describe the organisational design of your local service - what do you think comprises its constituent parts, and how are these arranged and interrelated?

How would you represent it as a diagram? (When making sense of complex situations it can help to sketch out different ways in which constituent parts can be represented in relation to each other.)

Does the arrangement that you have sketched have a particular shape, and does this have any significance in representing where service delivery decisions are made and how they are supported? Is there an ‘official’ representation of the shape of your healthcare organisation? If it differs from your initial sketch does this raise any challenges to your account of where service delivery decisions are made and how they are supported?

Letter 2: Representing Health Service Complexity - The Big Picture

Dear Marie,

Thanks for your swift response - I agree that it seems as if there are lots of jigsaw pieces but no overall picture to decide how they should all fit together, or to even know if we have all of the pieces in our possession. So to help you I will describe a big picture, one that will serve as a reference to locate and arrange the constituent parts, and will use it to navigate around the complex world of healthcare delivery. One advantage of this is to avoid a parochial view that is merely concerned with local issues and partisan professional interests. Furthermore, it will support a central focus on the service user.

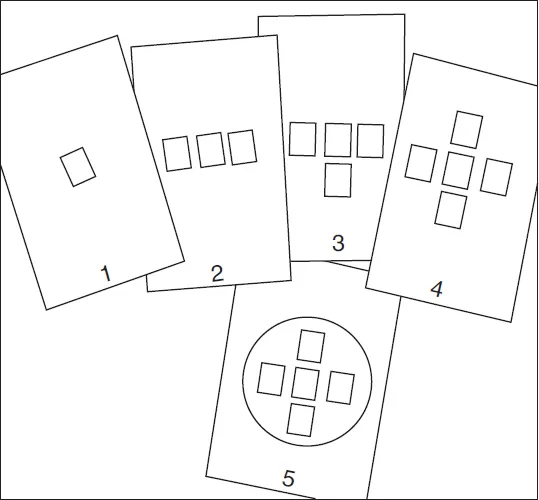

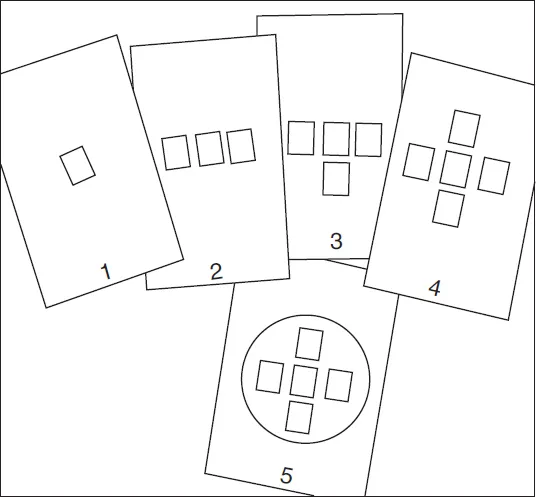

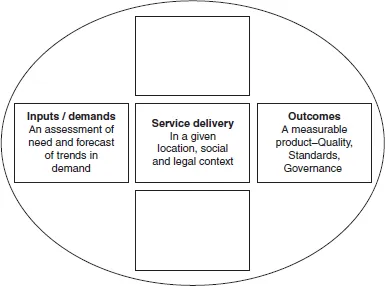

Whilst I accept that all models reduce real world complexity, they bring into focus different service elements and their interrelatedness. Once identified, these elements can be explored in relation to decision making. After reading this you might consider that the model needs developing - feel free to do so, it is merely a tool to assist your understanding of the whole. This model, which I will describe next, has five principal elements of which the central one is frontline service delivery.

IMAGE 2 From an office in the Netherlands

IMAGE 3 Sketching out a model

(Taking some leaves of cartridge paper from his folio he began sketching the model, or as he labelled it a ‘big picture’, to include in the letter.)

Element 1 concerns service delivery that lies at the heart of any healthcare organisation. Healthcare should focus on the service user’s needs. Often they are thought of as patients, implying a relationship between the individual and the organisation based on an illness model. However, such a model might not be appropriate as a service can embrace a health perspective where people access it for reasons other than diagnosis and treatment - hence employing the label ‘service user’ avoids the medical (illness) model association and offers scope for a different user - provider relationship.

The place of service delivery is varied, but wherever that is care needs to be delivered in a safe environment with safe processes. This requires robust governance arrangements that address a range of legal, regulatory, professional, policy and economic factors.

FIGURE 1 Element 1 Understanding Service Provision

Element 2 directs attention onto the trajectory of the service user as they access services from within a particular community, use the service and ultimately progress to some other destination, possibly returning to the host community. It follows that service delivery needs to be responsive to demand, and this requires information about its level and nature. This is termed health intelligence and involves a methodology used to assess the designated population’s healthcare needs. Furthermore, any measurement of need requires a clear understanding of what exactly is understood by the term ‘health’ - this, however, is a movable feast, and there are different views about health and the meaning of being healthy.

FIGURE 2 Element 2 Service demands

Element 3 continues the theme of a service user trajectory or journey, and directs attention towards the endpoint of exiting the service. At this stage questions are asked about service delivery processes and their outcomes. These might include: What was the experience of service provision along the service user trajectory? Did service provision achieve its goals for the particular service user? To what extent did provision match demand? Information analysis at this juncture facilitates the generation of findings and conclusions about service quality, effectiveness and efficiency. Naturally, this analysis is no mere paper exercise - the information is used in decision making about provision, processes, resources, quality enhancement and strategic direction. All service delivery requires resources which are the focus of the next element.

FIGURE 3 Element 3 Service outcomes

Element 4 represents service resources and highlights that nothing occurs along the service user trajectory without them. Even a voluntary service requires resources (such as a place, people, time and possibly equipment). When I speak of resources I’m referring to financial, physical, human, and information.

Financial resources - the service has to be paid for from somewhere. The funding can come from charity, the service user, an insurance scheme or public taxation (or a combination of these). Without resources nothing happens (as some English NHS Trusts demonstrated in 2007 when they addressed local financial deficits by unit closures and staff redundancies). A business plan should underpin resource management.

Financial resources enable staff to provide services - healthcare delivery is essentially a social organisation combining the efforts of a multidisciplinary workforce. Resource management determines the mix of staff with defined levels of expertise to deliver the service as planned. It also necessitates understanding of the intellectual resources of the staff team, their knowledge and experience that is often forgotten when plans are made to alter staffing teams, skill mixes and establishment levels.

Service delivery involves the utilisation of physical technological resources...