![]()

1 What is a growth mindset?

Carol Dweck has devoted her life and career to the study of achievement and success. As one of the world’s leading researchers in the fields of personality, social, and developmental psychology, she has spent decades exploring beliefs about intelligence and ability, and how those can impact on performance and attainment. Through this raft of studies, she formulated the theory of fixed and growth mindsets, summarised in Mindset: How You Can Fulfil Your Potential.1

In the fixed mindset, you believe that your qualities are carved in stone. You are born with a certain amount of ability, and that is all there is to it. Some people are better than you. Other people are not as good as you. But your abilities are fixed, and there is nothing you can do about it. Dweck describes how her own experience of education inculcated the fixed mindset, with particular reference to her sixth-grade class:

Even as a child, I was focused on being smart, but the fixed mindset was really stamped in by Mrs. Wilson, my sixth-grade teacher. . . . She believed that people’s IQ scores told the whole story of who they were. We were seated around the room in IQ order, and only the highest-IQ students could be trusted to carry the flag, clap the erasers, or take a note to the principal. Aside from the daily stomachaches she provoked with her judgmental stance, she was creating a mindset in which everyone in the class had one consuming goal—look smart, don’t look dumb. Who cared about or enjoyed learning when our whole being was at stake every time she gave us a test or called on us in class?2

One of the by-products of the fixed mindset is the impact it has on our own self-image. If we only have a fixed amount of ability, it becomes a priority to demonstrate that we have a lot of it if we are to preserve our self-esteem and status. Therefore, Dweck theorises, in the fixed mindset the priority is to “look smart at all times and at all costs.” This leads to the subterfuge of creating an appearance of competence or to the avoidance of situations in which you might be found wanting. I’ve seen this in the classroom so many times that I have lost count. The students who would rather get sent out than read aloud. Students who become the class clown to avoid having to write at length. Students who hide, shrinking back into themselves as classmates raise their hands, every fibre of their body language reading “please don’t pick me, please don’t pick me . . .” Why not? Because, if I pick them and they get the answer wrong, they will look stupid. They will look dumb. Their deficiency will be publicised. And this will define them as people – they will be the one that doesn’t know the answer.

On the other side of this, however, is the growth mindset. In this mindset, you believe that the abilities and qualities you are born with can be developed and cultivated through effort, application, experience, and practice. With the growth mindset in place, we see challenging situations as opportunities to learn and grow. When we make a mistake in our reading or writing, we learn from it and improve the next time we come across that word or that expression. When the teacher asks a question, we think about it, and we are happy to explore it together with our classmates to help refine and develop our thinking, leading to greater and deeper understanding. The process helps us to improve. To grow. And even if we don’t know the answer right now, if we work at it, listen carefully and apply ourselves, we will know it soon. In the growth mindset, Dweck suggests, the priority is “learn at all times and at all costs.”

These mindsets have implications for our behaviour in learning situations and for the outcomes we are likely to experience. When faced with a challenging task, for example, if we are in a fixed mindset, we are likely to seek to avoid it. What if we fail? That will surely prove that we haven’t got what it takes. If we fail, we will be a failure. In contrast, in the growth mindset, we will see a challenging task as an opportunity to test ourselves and to learn and grow from the experience. We probably won’t get it on the first attempt, but that’s not a problem – we will get some of the way there. On our second attempt, we’ll get a bit further. On the third, further still. Eventually, we’ll crack it. Then we can move on.

The second area where the mindsets have a significant impact on the way we behave is in our attitude to effort. In a fixed mindset, effort should not be needed. If we have the ability, we should be able to do it without trying too hard. If we need to put a lot of effort in, it’s a sign that we don’t have the ability – and therefore the effort is pointless. In a growth mindset, however, we recognise that effort is necessary in order to grow. As Carl Sagan says, “the brain is like a muscle. When we think well, we feel good. Understanding is a kind of ecstasy.”3

Third, the mindsets impact the way we respond to criticism. In a fixed mindset, critique of our performance is critique of us, of our very being. When we’re told we’ve not done well at something, it is a criticism of our ability and it defines us. However, in a growth mindset, we see critique and feedback as essential to help us grow and improve. We recognise that we won’t ever be perfect and that we can continue to improve – not because we aren’t good enough, but because we can be even better, to paraphrase Dylan Wiliam.4

Finally, our mindset influences the way we see the success of others. In a fixed mindset, we can feel threatened by the success of others because we see them as being better than us. This is the mindset that sees the flurry of “what did you get?” questions when an assessment is handed back with a grade on it. What is happening in this situation is that the students are trying to establish their position in the hierarchy of ability in the room. Where do I stand? If I was being taught by Dweck’s Mrs Wilson, where would she be sitting me in the room? Towards the top? Or towards the bottom? The learning experience of the feedback from the assessment is invariably lost in the quest to salvage self-esteem. I have seen children rip up their work when they’ve got it back with a poor grade on it, as though destroying the evidence will prevent it from existing and damaging their self-image. “Look smart at all times and at all costs” taken to extremes.

In a growth mindset, however, we can find lessons and inspiration in the achievement of other people. We want to learn from them. What’s their secret? How did they do it? I want to find out so that I can do it too.

As I read Mindset, I saw again and again examples pertinent to my own classroom experiences of students exhibiting the fixed mindset and, as a result, limiting their achievement. The frustration of seeing students afraid to try, unwilling to commit to challenging tasks, content to sit back and refusing to push themselves. Here was a wealth of research attributing these behaviours to students’ beliefs about their own abilities and, crucially, providing a template to change those mindsets.

Growth mindset study 1: changing mindsets

One of the studies5 conducted by Dweck and her colleagues explored how mindsets could be changed. In the study, two groups of students were given study skills workshops. In one workshop, students were presented with a range of study skills and ways of working to help them learn better. In the second workshop, students were given the same study skills, but they were also given an intervention which explained some of the basic neuroscience of learning. They were shown how the brain grows and strengthens when you learn new things.

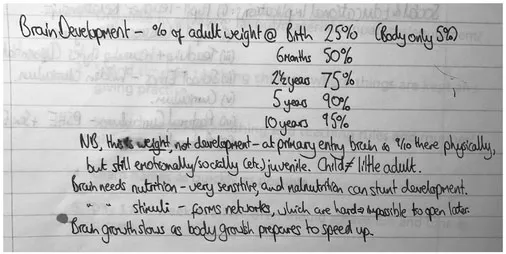

This was new information to me. I am an English graduate; I don’t have any Science qualifications beyond a GCSE. In my teacher training notes, the only reference I could find to cognitive science occurred in one section of my notes (see Figure 1.1). There is just one line there that hints at cognitive science: “[Brain needs] stimuli – forms networks.” It strikes me as strange that I got through so much of my career without really understanding what was happening inside the brains of the children I was trying to teach. Perhaps I could have benefitted from Dweck’s intervention at an earlier stage. Here is what I have learned about what happens in the brain when we learn something.

Neurons are brain cells; synapses are the connections between neurons. When learning takes place, a new synapse is formed. At first, this connection is fragile and tentative, but every time it is used again it strengthens. Eventually, well-trodden pathways between neurons become networks which can be travelled rapidly, instinctively and unconsciously. This is why I can drive my car without really thinking about it, but why I need to look up the year of Shakespeare’s birth every time I want to know it. It’s also why our brain can play tricks on us, looking to run through well-established neural networks even when the situation demands a road less travelled.

Figure 1.1 My handwritten PGCE notes, circa 1996

Neural or synaptic plasticity is the ability of a synaptic connection to develop in strength and efficiency. It is why, if we want students to learn things, we need to get them to repeat them, and why revision – seeing things again – is such an important process. The formation of these neural networks in our brains means that we need to plan for learning which encourages repetition and channels students’ energies into building strong, resilient and efficient synaptic connections.

Learning the basics of cognitive science makes sense of the growth mindset. It seems self-evident that the forming of new synaptic connections and the development of strong neural networks is “growth” in the genuine physical sense – the formation of a new or stronger connection in the biology of our brains. The roots of Dweck’s “the brain is a muscle – it gets stronger the more you use it” metaphor lie in the growth of the brain’s synaptic connections.

Students in Dweck’s study were provided with an overview of cognitive science and neural plasticity alongside the study skills which formed the content of the workshop for the control group of students. Teachers didn’t know which workshop students were attending, but they reported seeing significant impacts on the motivation and achievement of those who had attended the growth mindset workshop. And it didn’t stop there: those in the growth mindset workshop showed an improvement in their grades in mathematics, leading to them outperforming those students in the control group, who had been given the study skills alone.

Implications for practice

It seems so simple: explain how the brain works, then sit back and watch whilst student achievement rockets upwards. Of course, it’s never that simple! But essentially, the principle stands. Once the idea of neural plasticity is understood, it is then possible for learners to begin the process of shifting their mindsets. They begin to understand that the brain is actually growing and strengthening connections. It becomes clear that a growth mindset is not just a theory, but a truth.

Growth mindset study 2: the power of praise

Dweck and her colleagues also studied how mindsets are transmitted. In particular, in one famous study6 she explored how praise transmits mindset messages to children.

In the first part of the study, children were all given a non-verbal IQ test. The test was matched to their age and aptitude, so most of the children got good scores on the test. Following the results, the children got three types of feedback:

- Intelligence-focused feedback: “that’s a really good score; you must be really smart at this.”

- Process-focused feedback: “that’s a really good score; you must have tried really hard.”

- Neutral feedback: “that’s a really good score.”

The key to this experiment was the message transmitted through the feedback about what the adult valued in the child’s success. In the first type of feedback, the message was that the adult valued intelligence or ability. It implied that the child was successful because of their innate talent, or that they were naturally good at these kinds of puzzles. In the second type of feedback, the message was that the adult valued the process that allowed the child to arrive at their success: their strategies for solving the problems, their effort, their focus, their persistence. The neutral feedback formed the control group: their success was noted, but not attributed to any particular quality.

Dweck and her team then began to explore the impact that the different types of praise had on the children in subsequent phases of the experiment. First, they offered the children a choice of a more difficult test, where they were likely to make mistakes but would certainly learn from the experience, or a test very similar to the one they had just done in which they would surely be successful. The results were astonishing. Over two-thirds of the children who had been praised for their intelligence opted for the easier option, whilst over 90 per cent of the children who had been praised for their process opted for the more challenging test.

Why might this be? Could such a subtle distinction in language really cause such a wide variation in the willingness of children to take on challenges? Dweck’s supposition is that the messages within the feedback created mindset conditions in the children. When praised for their intelligence – “you must be so smart at this” – the children heard “the grown-up thinks I’m talented. That’s why they admire me, that’s why they value me.” Therefore, when faced with a choice between a test in which they might make mistakes or one in which they would surely get a high score, they opted for the latter. It would maintain the image of intelligence which had garnered the praise from the adult in the earlier round of the experiment. The children had entered a fixed mindset, and their goal was performance-focused: to get a high score and to look smart at all costs.

By contrast, the children who had been told “you must have tried really hard at this” heard that the adult valued the process that they went through, the strategies they were using, and the fact that they were taking on a challenge. When they were faced with the same choice, they were willing to take on the harder challenge because trying something difficult was what had got them the praise in the earlier round. These children had entered a growth mindset. If they made a mistake on the hard task, they didn’t worry that the adult wouldn’t think they were talented. Rather, Dweck suggests, if they didn’t take on the more difficult challenge, they would miss an opportunity to grow and the adult would be disappointed in them.

The experiment wasn’t finished there, eith...