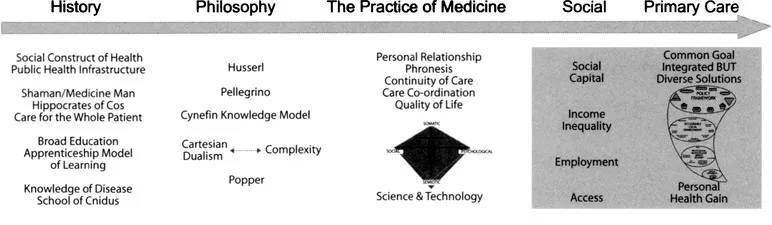

SECTION THREE

The practice of medicine: healing

In particular I believe that cure is rare while the need for care is widespread, and that the pursuit of cure at all costs may restrict the supply of care, but the bias has at least been declared.

Archie Cochrane61

Medical care - who determines what it is, and how is it negotiated between patients and doctors? It is an important question to reflect upon - particularly in light of the philosophical foundations of medicine. Is there a unifying model of health and health care that overcomes the Cartesian reductionism of the past centuries?

Healing is the ultimate goal of medicine. Illness, rather than disease, brings the patient to the doctor. Many illnesses are not associated with a definable disease, and the classical model of curing a disease does not apply to healing of the illness. Healing is the process of coming to terms with ones illness, making sense of that experience in light of ones life circumstances. The relationship between the doctor and the patient creates the therapeutic environment for healing.

The first chapter in this section describes the epidemiology of illness and disease in the community. Illness is common, disease is rare. However the fear of illness and disease has increased markedly over the past 40 years despite the fact that we never experienced better health ever.

The second chapter explores the related but distinctive notions of disease, illness and health. Disease is social in nature, whereas illness and disease is of a personal nature. A dynamic balance model of health is proposed that integrates the somatic, mental, social and sense-making (semiotic) aspects of the health and illness experience, and offers a means to overcome the prevailing Cartesian dualism in health care.

Medicine needs to re-emphasise the need to care. The third chapter argues that medicine must adapt its limited knowledge in the context of a unique understanding of our patients’ needs. Care is based on a personal relationship between the doctor and his patient. This relationship is informed by the diverse knowledge arising from psychoneuroimmunology, technology and evidence-based medicine, all of which affect the process and the outcome of care.

The final chapter examines general practice/family medicine in more detail. The discipline is defined in relationship terms and by its commitment to the person in his community. The personal relationship between doctor and patient enhances the consultation through patient centredness, trust, knowledge about each other and, ultimately, wise clinical decisions. The ongoing relationship provides much-needed stability in a rapidly changing healthcare system, equally benefiting patients and the system.

CHAPTER 10

The epidemiology of illness and disease

Every scientific truth goes through three states: first, people say it conflicts with the Bible; next, they say it has been discovered before. Lastly, they say they always believed it.

Louis Agassiz (1807-1873)

How healthy are the people in our community? Looking at all the media hype about the threats caused by old and emerging diseases we all must be on guard all the time.

How true are these threats really? How much are we influenced by the constant bombardment of threat in our environment? Are we as doctors fuelling the fear of disease, and the vulnerability to succumb to them? Shouldn’t the fact that we survived the evolutionary pressures in pretty good shape be reassuring?

There are two ways of assessing the health state of a community, one by looking at mortality statistics, the other by asking people to report on their health and their responses to experiencing illness.

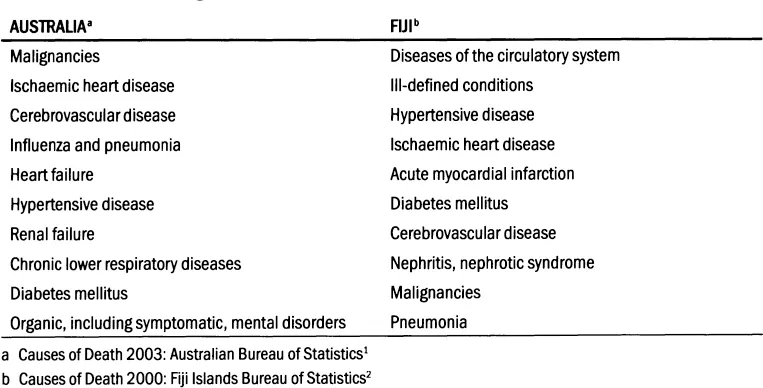

Mortality statistics have one big irony; we all are going to be one at some stage. The accuracy of mortality statistics is limited by the fact that they are largely compiled on the basis of clinical rather than post-mortem assessments. Mortality data nevertheless are helpful for the planning of health service priorities (see Table 10.1), but they do not tell us anything about the impact of the underlying disease(s) on life. In particular, mortality statistics do not help us in understanding and dealing with a particular patient’s illness experience in the consultation.

TABLE 10.1 Leading causes of death: Australia and Fiji1,2

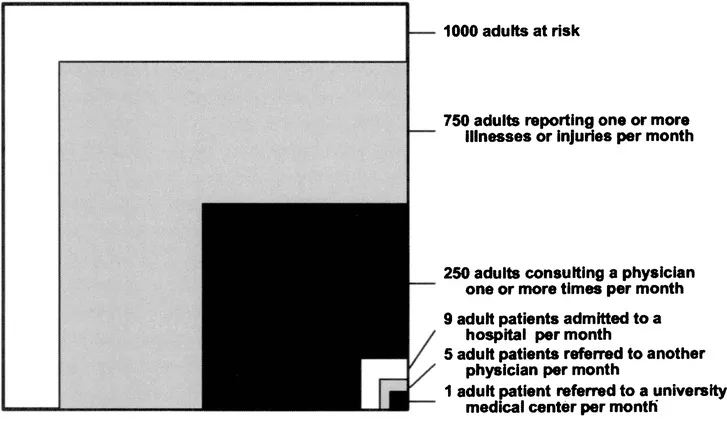

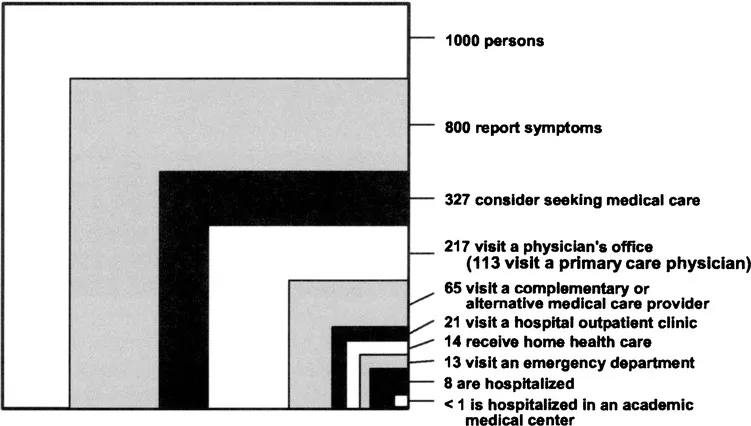

Figure 10.1 Monthly prevalence estimates of illness in the community and the roles of physicians, hospitals, and university medical centres in the provision of medical care. (Reproduced from White K, Williams F and Greenberg B. The ecology of medical care. New England Journal of Medicine. 1961; 265: 885-92,3 with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society.)

White and colleagues explored the health and illness experience of the community and described a rather bright picture - most members of a community perceive themselves to be healthy and able to cope by themselves with most minor illness symptoms. Only a small percentage of those seeking medical care are subsequently diagnosed with a disease and/or require specialised medical services (seeFigure 10.1).3

Community health and illness has changed little between 1961 and 2001. Larry Green and colleagues reviewed current data, and found that many more patients experience some illness symptoms and that about 30% more people seek care, mostly from complementary and alternative medical care providers.4 These changes may well reflect the impact of the media hype alluded to above. There also has been a shift towards ambulatory/community care reflecting to some extent the needs of an aging population, and to another our greater ability to provide care based on technological advances. However, the number ofpatients requiring hospital care remains unchanged (seeFigure 10.2).

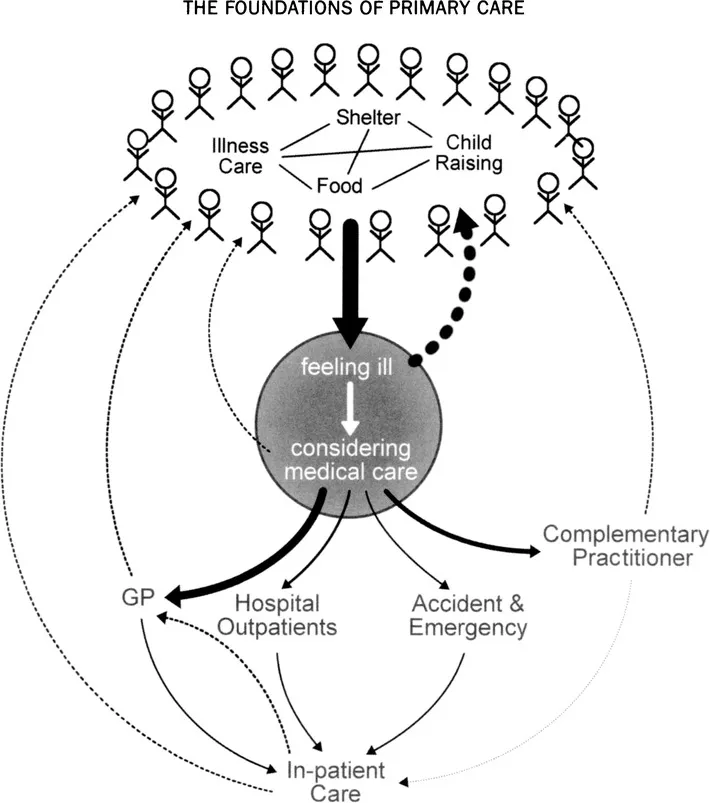

It is rather remarkable how stable the epidemiology of disease has been over these four decades. It is equally remarkable to see that at a time when the population at large has never been healthier, the population also appears to be more afraid than ever of illness and death.5 Figure 10.3 illustrates an analysis of the community’s health-seeking behaviour - two questions of great importance arise: ‘How did the community’s perception of being ill change?’ and ‘How do individuals decide when and whom to consult when perceiving the need for medical care?’.

Figure 10.2 Re-analysis of the monthly prevalence of illness in the community and the roles of various sources of health care. (Reproduced form Green L, Fryer G, Yawn B, Lanier D and Dovey S. The ecology of medical care revisited. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001; 344:2021-5,4 with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society.)

Figure 10.3 Care-seeking in the community: experiencing illness is common, seeking care is much less common.

Summary Points

Over the past 45 years the illness experience within Western communities has increased significantly; however, the incidence of serious disease has remained stable.

People never lived a longer and more disability-free life ever; however, they appear to be more fearful of illness and death.

CHAPTER 11

Disease, illness and health

It is more important to know what patient has a disease, than what disease the patient has.

Sir William Osier

Each man has his particular way of being in good health.

Emanuel Kant

The focus of medicine has shifted beyond the question of an art or a science. No one doubts that sciences have improved our understanding of disease; however, patients do not experience diseases, they only experience the consequences of these.6 Every patient is unique, and no two patients share the same illness narrative even if they have the same disease label.

Illness describes a subjective experience; it is the patient’s account about his state of self.7 Disease, in contrast, is the objective state of physical alteration, defined by abnormal measurements...