![]()

Part I

Approaches to Chinese discourse

![]()

1

Chinese conversation analysis

New method, new data, new insights

Kang-Kwong Luke

Background

As a new method for the study of talk-in-interaction, Conversation Analysis (henceforth ‘CA’) has its beginnings in Harvey Sacks’ lectures (Sacks, 1992) and a number of key publications by Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson in the 1960’s and 70’s (Jefferson et al., 1987; Sacks et al., 1974; Schegloff and Sacks, 1973, etc.). In Sacks’ lectures and publications, one finds, for the first time, close observations of how situated talk is designed to be heard in particular ways. One also finds in Sacks’ work detailed descriptions of the procedures (or ‘ethnomethods’ – see Garfinkel, 1967) with which parties-in-interaction jointly achieve intersubjectivity through sequences of turns-at-talk. Scholarly treatments of language prior to Sacks, as seen in the publications of linguists and philosophers of language for example, suffered from a number of theoretical and empirical problems. Theoretically, linguistic signs were conceptualized as codes, and communication as an encoding and decoding process (Saussure, 1959; Russell, 1940). For a variety of reasons, form was given precedence over meaning (Bloomfield, 1933; Chomsky, 1957). Once form is divorced from meaning, it is impossible to put under scrutiny the true relationship between them – how, in detail, meanings and interpretations are constructed by parties to a conversation with the help of forms. Empirically, while ‘context’ has always been known to be important, in practice more lip service than undivided attention has been paid to it, so much so that one is hard pressed to find a definition or operationally feasible specification of what constitutes ‘context’. Add to this the belief that the study of language could proceed profitably by pondering over single sentences in isolation, which furthermore are invented or re-constituted through memory, and the vicious circle is complete.

Sacks’ ground-breaking contributions include abandoning the code theory and replacing it with an indexing theory, which maintains a constant and close dialogue between form and function, as well as giving context (and interaction) the central position that it deserves by insisting on the use of naturally occurring data.

My purpose in this chapter is to introduce CA to students of Chinese discourse as a well known but relatively little understood method. My aim is therefore not to offer a literature survey of the entire field of Chinese CA, but to show, through a close analysis of one specimen, some basic principles of CA and how it works in practice.

Conversation analysis: new method

As alluded to above, the CA method is built upon the basis of three essential elements: (1) naturally occurring data, (2) close, contextualized, time-sensitive form-function analysis, and (3) an intersubjective perspective.

Naturally occurring data

Data are deemed ‘naturally occurring’ if their occurrence is not the outcome of prompting (e.g., interviewing), experimentation, or some other forms of contrivance, i.e., if the text or talk being captured for analysis is produced under natural conditions. CA’s insistence on naturally occurring data does not arise out of some romantic notion of naturalness (whereby ‘the natural’ is deemed superior to ‘the artificial’); rather, it is necessitated by a single-minded objective to pin down and subject to close scrutiny, phenomena as they present themselves to us in the form of everyday life experiences. In this regard, as an empirical science, CA is data-driven through and through (as opposed to theory-driven, as in many forms of linguistics, sociology and psychology). Typically, the starting point of CA is a recording (audio or video) of some naturally occurring talk. These recordings are then subjected to repeated, close listening (or watching) and detailed, fine-grained transcription (Jefferson, 2004).

Close, contextualized, time-sensitive form-function analysis

In examining the recordings, using data transcription as an aid, the analyst proceeds slowly and carefully, word-by-word, line-by-line, and moment-by-moment (hence ‘time-sensitive’), with her attention focused sharply and squarely on the forms (designs) and functions (actions) of each utterance in the conversation under scrutiny, constantly inviting form and function to interrogate each other by specifying as accurately as possible how a particular design is used to carry out a particular (social) action. This necessarily dense description will be illustrated with reference to a small sample of data in the next section.

An intersubjective perspective

Critical to any measure of success in such an analysis is the adoption of an intersubjective perspective. An intersubjective perspective necessarily involves, and is based upon, an ‘emic’ perspective (Pike, 1967), i.e., a perspective from within the interaction. What’s more, ‘intersubjective’ is used in the present context in opposition to a single, all-encompassing, ‘objective’ perspective, as assumed by ‘the scientist’, or an equally single, all encompassing, ‘subjective’ perspective, as adopted by the non-scientist (e.g., the literary critic or ‘the man on the street’). Rather than setting out to uncover or discover a scientific objectivity, or put forward a purely personal or subjective reaction, the CA analyst aims to produce a description of how sense is made of forms from both the point of view of the speaker and the point of view of the hearer (with the roles of ‘speaker’ and ‘hearer’ constantly changing, shifting or rotating, from one moment to the next). Any claims resulting from such an analysis are in principle open to verification by others on the basis of inspecting the same piece(s) of data.

To complete this quick sketch of the CA method, a few more comments should now be made as to what CA is not. First, in spite of its name, CA’s object of study is not confined to everyday, face-to-face conversations. As a method, CA is applicable, and has indeed been applied, to the study of talk and interaction in a variety of non-face-to-face settings – telephone conversations including helplines (Schegloff and Sacks, 1973; Luke and Pavlidou, 2002; Baker et al., 2005), non-verbal activities (e.g., Ivarsson and Greiffenhagen, 2015 on poolskating), video communication (Harper et al., 2017), and media and other texts (Eglin and Hester, 2003).

Second, while talk-in-interaction is indeed one of the main foci of CA work, as a method, CA does not confine itself to the examination of talk in the narrow sense (of the words and structures of a language). Goodwin (1979) and Schegloff (1984) are two early examples of applications of CA to the study of embodiment as it is deployed in the design of actions. More recently, closer and finer reference has been made to the ‘attending’ features of talk – gaze, facial expressions, hand gestures, body postures; in short, multimodality (e.g., Li, 2014). In order to capture as much of the total communicative situation as possible, analysts are relying increasingly on video-recordings in CA research.

Third, it is sometimes thought that CA is interested primarily in ‘structural’ issues, such as the mechanisms of turn-taking. Nothing could be further away from the truth. Everything that conversational participants do – every element in the design of their utterances which is deemed, by the participants themselves, communicatively meaningful, including not only how turns are taken but also word choice, intonation, prosody, head movements, gestures, facial expressions and the rest, is done in the service of one single goal, namely, the formation and execution of social actions (e.g., greetings, invitations, congratulations, condolences, complaints, consolations, etc.). CA’s interest is therefore in action and interaction, which by definition involves meaning and not merely structures or forms.

Finally, and related to the previous point, there appears to be a widespread misconception that CA does not account for, and even positively forbids the use of, ‘social’ and ‘cultural’ information ‘outside of’ the immediate conversational context. Again, this is emphatically not the case. Because of CA’s interest in meaning and action, in carrying out an analysis, the analyst must attend to any information necessary for a better understanding of the design or interpretation of an utterance. Whether this knowledge is deemed, from some point of view or other, as ‘personal’, ‘social’ or ‘cultural’, is of no concern to CA. The only thing that matters is whether the relevance of the information to the analytic purpose at hand can be shown to be anchored in the data itself, and not, for example, a figment of the analyst’s own imagination (See Hester and Eglin, 1997).

Doing CA: an example

There is no better way to show how the CA method works than by going through an example of data analysis. Through the exemplification, it can be seen what naturally occurring data is like, how it is pre-treated (or transcribed) to facilitate observation and scrutiny, how contextualized, moment-to-moment analysis proceeds and how an intersubjective perspective comes into it.

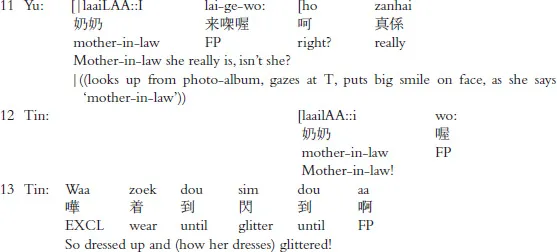

The piece of data in question is a snippet taken from a video recording of a conversation among three friends, Mandy, Yu, and Tina (all pseudonyms). The conversation took place in the living room of Mandy’s apartment (in Hong Kong), and was conducted in Cantonese. In keeping with CA practice, prior to the recording, the participants were given no instructions as to what they should talk about other than “to have a nice chat with one another”. As it turned out, one of the first topics that came up was weddings, because Mandy was recently married, and Tina’s brother happened to have gotten married also a week or so before.

As we join the conversation, Yu is ‘telling Mandy off’, in a jocular sort of way, for not wearing a traditional Chinese gown at her wedding. Yu believes, in line with common beliefs in Hong Kong, that only wives (as opposed to concubines or mistresses) are entitled to proper wedding ceremonies, where they are expected to wear a traditional Chinese wedding gown. In an attempt to drive home her point, Yu puts the following rhetorical question to Mandy: “Only wives can wear the traditional gown. You wouldn’t want to be a mistress, would you?”, at which point Mandy and Tina both burst out laughing. Tina then offers, in pursuit of the theme of ‘wives vs. concubines/mistresses’, the following report about her mother in the next turn:

Data transcription

Before developing an analysis of this piece of data, it will be useful to take a closer look at the transcript, in order to appreciate how much effort has gone into the transcription, and why it is necessary for such a detailed written representation of the video to be made. The way in which the transcription is done, and the symbols that are used for this purpose, are based, as it is now well known, on a set of conventions first devised by Gail Jefferson in the 1960s and 70s. These transcription conventions have become so well established that they are now widely known under the name of ‘Jeffersonian transcription’, and are adopted by CA practitioners as a field standard.

A look at the data transcript in (1) will reveal a number of readily discernible features. First, the transcription is presented essentially as a verbatim representation of the talk as captured on the video recording. Utterances which might otherwise be dismissed as ‘false starts’, ‘repetitions’, ‘half-finished sentences’, or ‘trail-offs’ are recorded as faithfully as possible, with no prejudice as to why they might have the shape that they do at those points in the conversation. In line 10 of the transcript, for example, Tina can be seen to be going on (from what she has just said in line 7) to say some more about her mother (or, in technical parlance: to produce another turn-constructional unit). But just as she is beginning to construct that next utterance, Yu comes in strongly to proffer an agreement in the form of an understanding display (in line 11). As a result of this overlap, Tina’s just-started utterance trails off and is (at least temporarily) abandoned, to make way for Yu’s turn. Even though Tina’s utterance in line 10 is unclear and incomplete, an attempt is nevertheless made in the transcription to indicate that she did start saying something at that particular juncture in the int...