![]()

1 The Seeds of Continuous Improvement

INTRODUCTION

Today, most organizations are still dealing with the repercussions from the largest recession since the Great Depression. The recent meltdown and tortoise-speed recovery have created a disturbing trend in which leaders have their organizations stuck in short-term survival mode. Granted, many of these immediate survival tactics were necessary as the financial crisis unfolded before our very eyes. However, too many executives are continuing to drive their businesses in this short-term, reactionary survival mode as the new cultural norm. These respective inconsistent leadership behaviors are a major contributor to recent benchmarking data indicating that over 80% of Lean Six Sigma and other formal improvement initiatives are derailed and repeating the same familiar birth-death cycle of continuous improvement programs since the 1980s. At the beginning of each of these life cycles, the early successes have a hundred fathers, but when improvement fails, it becomes an orphan. With each of these cycles, the word continuous keeps falling out of continuous improvement. Today, many organizations could add more to their financial statements through successful continuous improvement initiatives than they will add via their wavering and reactionary hot lists of actions.

Continuous improvement is not always the most enticing topic for executives because it reveals waste and root causes and establishes accountability and metrics for progress. On the one hand, the concept is decades old, and people have talked a good game about continuous improvement under a variety of different banners and buzzwords. On the other hand, the concept is relevant because, like it or not, the need for continuous improvement never goes away. Yet there are always excuses to postpone continuous improvement that, when one thinks about this statement, it is a silly choice. Authentic excuses such as the ones that follow are easier than performance:

• “There’s no money in the budget for improvement until 2012.”

• “The time is not quite right for improvement.”

• “Improvement is not in my goals and objectives.”

• “We finished our continuous improvement program years ago.”

• “We eliminated our Six Sigma program. … It did not work for us; we’re different.”

• “We don’t have the time and resources to improve and do our regular jobs.”

• “If I had more time, I would have found a better way.”

Move over Sophocles! Are these comments inspirational or tragic? Today, many organizations may not openly admit it, but they have traded in their true commitment to Lean Six Sigma for many improvement-dysfunctional behaviors that are driving culture backward, all in the interest of illusive short-term results.

In the midst of our present anemic recovery, one of the greatest challenges of every organization is strategic and sustainable improvement. Whether your organization is a Fortune 500 corporation, a rapidly growing software start-up, an established small or midsize manufacturing company, a financial services organization, a pharmaceutical or biotech company, an aerospace and defense contractor, a services supplier to the automotive industry, a large construction company, a large healthcare institution, or part of the federal, state, and local government infrastructure—the urgency and magnitude for continuous improvement grows proportionally and often exponentially to the emerging global economic, social, and political challenges of the postmeltdown economy. Even federal, state, and local government agencies are under significant voter pressure to follow improvement practices of private industry and figure out how to do more with less. Unfortunately, government does not get it yet. After decades of existence, continuous improvement is the fast lane out of our slow economic recovery—and the fast lane of success in good times, bad times, and everything else between these two extremes.

CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT: A BRIEF HISTORY FOR THE UNINITIATED

Lean Six Sigma and most other improvement initiatives have their roots in the formal discipline of industrial and systems engineering. Within the typical industrial and systems engineering curriculum is a wide variety of courses on topics such as methods analysis and process improvement, management science, statistical engineering, financial engineering, engineering management, maintenance and equipment management, supply chain management, facilities planning and design, production planning and scheduling, inventory management, process engineering and development, operations research and process optimization, systems engineering, knowledge-based systems design, performance and measurement systems design, human factors and ergonomics, team-based problem solving, value engineering, and quality engineering. The details and body of knowledge presented in these courses are almost identical to what has been packaged in the various improvement programs of the past three decades. Industrial and systems engineering is the foundation for most of the analytical and human factors content of Lean Six Sigma.

The discipline of industrial and systems engineering is accredited to Frederick Taylor, father of scientific management, and Frank Gilbreth, a pioneer in motion study and creator of the 17 basic motions or therbligs (Gilbreth spelled backward with the th transposed). Shortly thereafter, there was Henry Ford, who wrote the first book about Lean in his 1926 classic, Today and Tomorrow. Taiichi Ohno, father of the Toyota Production System (TPS), was inspired by Henry Ford’s discussions about standardization, waste, and continuous flow production. Around the same time, Walter Shewhart, the father of statistical process control, was developing the discipline at Western Electric and later at Bell Labs, where he was introduced to William Edwards Deming.

During the era after World War II, Japan recognized that its recovery was highly dependent on these improvement topics. Dr. Deming and his expertise on statistical quality improvement and Taiichi Ohno with his industrial and systems engineering background and visionary thinking from Toyota took center stage in business improvement. Some level of complacency set in for America after winning the war. Rather than listening to the wisdom of Deming and others, we exported it to Japan, which was faced with postwar reconstruction issues related to manufacturing. Postwar Japan was severely constrained in terms of space, resources, time, cost, and their perceived low quality by the West. At Toyota, for example, there was a concern with quality and inventory levels and the costs and space consumption associated with each. Emulating what U.S. companies were doing was essentially not doable and unaffordable. As the story has it, Ohno visited an American supermarket and realized his vision of pull production. This became codified as an essential element of what was to become known as the Toyota Production System (TPS). Much of the TPS is Taiichi Ohno’s evolution of basic industrial and systems engineering improvements aimed at the unique inventory, quality, space, and natural resource limitations in postwar Japan. Development and implementation of the TPS was a lot of work—relentless, never-ending work—work that turned out to go unnoticed by the Western world until it revolutionized global manufacturing by 1980. Several others, such as Masaaki Imai, father of Kaizen, also became internationally renowned for the continuous improvement work at Toyota and many other Japanese companies. The single most important factor was their deployment of improvement in a perfect cultural environment characterized by honor, nationalism, teamwork and true empowerment, a relentless commitment to quality and perfection, prevention and improvement driven, quality at the source, shame for failure, extreme discipline, concentration on process and root causes, meticulous attention to details, and long-term focus, to name a few traits. Toyota and many other Eastern corporations mastered continuous improvement under the radar screen for years. The combination of the industrial and systems engineering tools and their national culture was a match made in heaven. During this same time, some U.S. companies with an appreciation for industrial and systems engineering were also involved in many of the improvement efforts, like pull production and two-bin systems, work cell design, plant layout, preventive maintenance, and continuous flow, that supposedly originated in Japan. However, the efforts in what was primarily “command-and-control” and “good soldiering” cultures back then were not as continuous and certainly not as impressive as the results of their Eastern counterparts.

When Toyota, Honda, Canon, Sony, and many others began dominating U.S. industries in the 1980s, America received its first wake-up call of continuous improvement. American executives, and educators began visiting these Japanese organizations and brought back what they thought that they observed. These visitors did not appreciate the human and cultural elements of their observations and instead repackaged and imported a discrete series of new and improved industrial and systems engineering techniques followed by their own vocabulary of acronyms and books on the topics. The long and the short of all this is that continuous improvement was exported from the United States to the East, where it was really deployed with a best-in-class style, and then the United States imported continuous improvement back to America. The chronic problem with continuous improvement in the Western world is a different culture and a different way of thinking. In the East, their leadership styles and culture turned out to be a perfect match for continuous improvement. In the West, many leadership choices, behaviors, and actions favor instant gratification and run counter to continuous and sustainable improvement. Much of this is driven by traditional cost accounting metrics and Wall Street expectations.

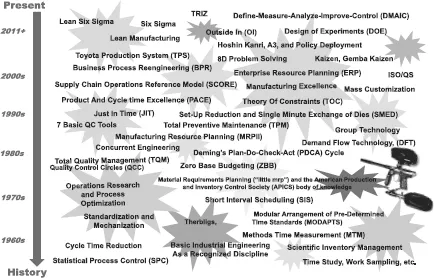

Thirty years ago, America became painfully aware of the importance of quality improvement, and executives were scratching their heads as they watched the 1980 NBC documentary, If Japan Can, Why Can’t We? This was a mammoth wake-up call for business improvement. We watched their industry success at reducing setups, defects, cycle times, costs, and inventories based on improvement techniques introduced by Taylor, Gilbreth, Ford, Shewhart, and Deming in the early 1900s. Suddenly, there was a high degree of interest in improvement, but in retrospect a poor track record of implementing and sustaining continuous improvement. A vivid memory from this time was executives making comments similar to, “If you think things are bad now, wait until the great Shenzhou (China —Land of the Divine) awakens.” Their predictions were right on the mark! Back then, Deming talked about constancy of purpose; unfortunately, we still have not found it yet with business improvement. The average executive lasts about 2 years in his or her position. The average birth-death cycle of various continuous improvement programs has been even less time in most organizations (although Lean Six Sigma has stuck for a longer period of time than its predecessor efforts). Many of today’s executives may have been through a partial or exhaustive paintball of bandwagon improvement initiatives (Figure 1.1) in their careers.

Within each of these improvement initiatives is their own vocabulary of acronyms, buzzwords, tools, and methodologies that has confused the business improvement playing field even more. Further, the experts promoted their own wares while discrediting the offerings of other competitors. They attempted to convince management with bogus advice, such as Lean is better than Six Sigma, Kaizen is quicker and simpler than Six Sigma, or the right sequence to implement improvement tools is 5S followed by Gemba walks, value stream maps, and muda analysis. Several vendors have popped up over time, offering their “canned” proprietary software applications, templates, and reports as an optional means to improvement. Continuous improvement has resembled an executive game of grabbing at straws and searching for the magic bullet. This spectrum of bizz-buzz combined with how leadership has deployed these initiatives has left many employees totally confused and turned off by the thought of another improvement program. For decades, organizations have been grasping at and bouncing between the improvement tools by themselves and missing the mark of how to deploy strategic improvement successfully. Unfortunately, the banners and slogans were, and continue to be, a short-term replacement for the tough work of implementing, benefiting from, and continuing onward with business improvement. I walked into a new client a few years ago, and one employee commented to me, “I know why you are here—because Mr. X [the chief executive officer] has read another book!” In another organization, an executive actually made the comment: “We need Lean Six Sigma because we finished our continuous improvement programs years ago.” Regardless of the ribbon du jour of improvement programs, continuous improvement is more leadership and common sense than rocket science and tools.

FIGURE 1.1 The paintball of continuous improvement. (© Copyright 2011 by The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc. [CEO].)

In retrospect, organizations have been on a random walk down continuous improvement street during the past few decades. Continuous improvement has been a concept that every executive in every organization definitely embraces in concept but not as a critical and sustainable element of business strategy in daily practice. There is a disturbing and well-documented birth-death cycle that exists with continuous improvement initiatives: When things are good, improvement is the first casualty because it is perceived to be no longer necessary. When things are bad, improvement is the first casualty because people do not have the time and resources to improve and do their regular firefighting jobs. Between these two extremes, improvement has been supported by temporary and wavering commitments, token agreements, follow-the-leader fad programs, massive training, and more going through the motions of improvement. Over time, executives and their organizations ride through many of these cycles, creating the separation disorder of improvement culture: People view improvement as “in addition to” rather than “an expected part of” their daily work.

Another historical fact about improvement is its continuous repackaging and remarketing under a different banner as if the concept never existed before. Organizations are sold down the road with another box of improvement with a different ribbon wrapped around it and new promises, but the contents of the box remain basically the same. As mentioned, much of what exists (and has always existed) in the boxes of improvement are the basic disciplines and solid fundamentals of industrial and systems engineering—exported to the Far East, implemented with great success, and imported back to America. Most gurus packaged improvement as the latest single-point tools, acronyms, and buzzwords, with no overarching and sustaining constancy of purpose. Dozens of books have been published on individual improvement tools with Japanese names. Organizations have introduced improvement programs like a pinball game in which everyone eventually forgets which balls gained or lost points. There has been an enormous focus on the tools (the means) and not enough focus on the leadership, systems thinking, infrastructure, and cultural elements of continuous improvement—the critical success factors that create sustainability and keep the “continuous” in continuous improvement. Executives have continually underestimated and oversimplified what it really takes to plan, organize, deploy, execute, and sustain a successful continuous improvement initiative.

Let us continue our walk through continuous improvement history to the present experiences with Lean Six Sigma. The impulsive leadership actions to the recent meltdown are but another example of a natural response to disaster, leaving executives and organizations running with the best of intentions but vulnerable to many bad choices. One of the most disturbing leadership choices through the recent economic crisis has been the across-the-board freezes on improvement when organizations need it the most. Through the meltdown and slow recovery, this expediency of impulsive leadership has trumped the propriety of logical improvement thinking, often creating a dazzling display of illusive short-term success. When people perceive improvement as a low priority, they tend to go into firefighting mode and lose sight of the most obvious fundamental: The only way to get better is to improve current conditions. Improvement is the process of getting from point A (current state) to point B (the improved state) through “structured principles and deliberate actions” that enhance stakeholder value, perfection, and excellence. Instead, many executives and their organizations are stuck in this mode of hyperinsanity: doing more of the same things with greater velocity and emotions and expecting to achieve different results. Like it or not, executives choose to replace the “structured principles and deliberate actions” discussed with “whack-a-mole actions,” hoping to achieve faster results. In many organizations, the continued reactionary management practices are becoming the new cultural norm that we refer to as acceleration entrapment: Organizations are so overloaded with multitasking immediate crisis after crisis that their people become ineffective at everything. Some justify their actions by blaming the fierce global economy. Other leaders revert to their great manager practices of stirring up the organizational pot and create the appearance of making things happen. However, the true root cause at play here is lack of constancy of purpose, which is driving culture backward, reducing employee commitment and trust, and placing these organizations farther behind in this new economy. In many organizations, these uncompromising leadership behaviors have created more waste and hidden costs and increased the need, magnitude, and urgency of strategic improvement. Today, for example, over 80% of Lean Six Sigma and other formal improvement initiatives are derailed and off point. Once again, executives are contributing to the laws of unintended consequences about improvement by their actions by repeating the same familiar birth-death cycle of continuous improvement programs since the 1980s. Organizations may have run out of steam with Lean Six Sigma but cannot afford to back-burner improvement. History shows us that the only continuous activity is the introduction of new buzzword branding for continuous improvement. This is the last thing that organizations need.

To ensure that the jargon of improvement is not complicated even further, this is a good time to provide more definition to terms that appear to be used interchangeably throughout the book. Strategic improvement is a large-scale improvement initiative that attempts to transform organizations to superior “breakthrough” levels of performance. Strategic improvement is a continuous process of improvement at a higher level. An example might be to reduce time to market for new products or length of stay in hospitals by 75%. Continuous improvement is an ongoing effort to improve products, processes, and services. Continuous improvement encompasses many activities under the umbrella of strategic improvement that tend to be more rapid and incremental by nature. In our examples, continuous improvement might involve dozens of concurrent improvement efforts to achieve these strategic objectives. Business process improvement is a form of continuous improvement that refers to the application of improvement to key transactional business processes to improve speed, quality, cost, or service-level delivery. Sustainable improvement is the combination of strategic, business process, and continuous improvement, executed to produce nonstop benefits over time without any disruptions in progress. Some may argue that sustainable is not good enough. Note that in our definition sustainable is not level; it refers to a sus...