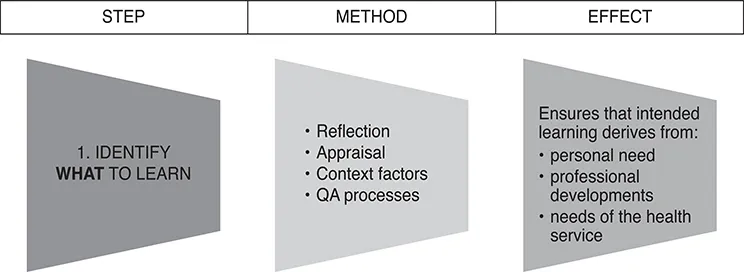

STEP ONE: IDENTIFY WHAT TO LEARN

Here we present the methods which can be used to help doctors identify what it is that they need or want to learn. Earlier, this step was presented as follows:

To identify methods of ascertaining what to learn, we gathered those listed in the literature, by medical Royal Colleges and similar organisations. We also spoke with a sample of doctors about how they actually decided what to learn until no further ideas were contributed.

However, the demands of regulation and transparency require that doctors not only reflect on their learning needs and wants, but that this should also be done consciously and recorded. We therefore recommend that:

The identification of learning needs/wants should occur within an appraisal or a professional conversation with a peer

The process and its outcome should be recorded.

The appraisal might occur on an annual basis, or more frequently, if required.

Appendix 2 presents a template record form for the appraisal or professional conversation session at which the doctor’s learning needs or wants are identified and recorded.

HOW CAN LEARNING NEEDS BE IDENTIFIED?

Learning needs identification can be seen as a formal process or can be an integrated part of professional life.

However, Grant (2000)23 points out that:

Exclusive reliance on formal needs assessment could render education an instrumental and narrow process, rather than a creative, professional one

Different learning methods tend to suit different doctors with different identified learning needs

Doctors already use a wide range of formal and informal ways to identify their own learning needs as part of their ordinary practice

These should be the starting point for designing formalised educational systems for professional improvement.

There is no commonly accepted definition of an educational need. Whole books are devoted to what an educational need might or might not be and what methods may be used to identify it. In the end, the methods used are simply a reflection of the view that is adopted about what an educational need actually is for the learner in question. The answer will be different for different learners. Norman24 points out that:

‘Learning needs are personal, specific, and identified by the individual learner through practice experience, reflection, questioning, practice audits, self-assessment tests, peer review, and other sources.’

He further suggests:

Traditional approaches to continuing education that rely on self-assessment and self-learning are likely to be ineffective

Centralised methods, such as regular relicensure or recertification examinations, are difficult to tailor to the characteristics of individual practices and are perceived as threatening.

The Good CPD Guide takes the view that methods of needs assessment for CPD must be appropriate to the characteristics of the profession and that it must be a part of the managed process of CPD. Needs assessment should be based in, and grow out of, professional practice.

In these times of transparency and accountability, there is sometimes a feeling that needs assessment should be done ‘objectively’ by an outside or independent agent. There is talk of doctors only being able to identify their educational ‘wants’ rather than their actual ‘needs’ (as though wanting something actually excludes the possibility that one might need it too!). It is often said that, given a free hand, doctors will only attend those educational events that concern things they already know and are interested in, rather than choosing the more challenging areas that are new to them. The evidence for such statements is rarely available.

The Good CPD Guide takes a different view of needs assessment, proposing that it is best seen as the result of three complementary processes:

The professional practice of the doctor

More formal processes such as audit or peer review

The standards and plans of the health service in which the doctor works.

There are many ways doctors can identify their learning needs in relation to these three processes. Some of these are presented below.

SHOULD ALL CPD BE BASED ON SPECIFIC LEARNING NEEDS?

Although The Good CPD Guide describes methods of needs assessment, this is not to suggest that all professional learning should be based on specifically identified needs. Indeed, professional learning is often aimed at general development or reinforcement of knowledge and skills. Given that major characteristics of professional practice are its unpredictability and the unique nature of each professional encounter, to base all education on known needs would be highly counter-productive and unprofessional. There must be a balance of general professional CPD and CPD which is aimed at specific needs or outcomes:

General professional CPD might be, for example, attendance at an international meeting for general updating purposes

CPD aimed at specific needs might be, for example, learning a new technique or skill, or making up for some identified deficit.

Both types of CPD are required.

Most of the methods listed simply occur as part of the normal routine of working. Some require a special effort to be made. Both approaches to educational needs assessment are acceptable and important. They form parts of professional behaviour.

The methods of needs identification described here, and gathered from the literature and reference to doctors’ own experiences will enable a balance of both types of CPD. It is a balance that must be maintained.

HOW DO DOCTORS IDENTIFY THEIR LEARNING NEEDS?

This section lists the many ways doctors either identify a need or want to learn more. The list was compiled from the literature, by the hospital departments and consultants involved in the research project, and by the original Good CPD Guide authors.

However, identification of educational needs as a routine part of everyday professional practice is perhaps not quite enough these days. It is necessary to state how those needs were identified and to do that more consciously. This simply demands the awareness that needs are being identified and putting together a learning and follow-up plan which does something about them.

When planning CPD, doctors should be able, allowed and encouraged to cite any of the methods listed in this section (or others, if necessary) as the reason for wanting to undertake the CPD requested. Perhaps a balance of formal and informal methods would be desirable, but the main point is to demonstrate that a needs assessment or reflection has occurred and that the CPD planned is a rational choice.

There are many ways in which an individual’s needs might be assessed. An appraisal or professional conversation with an appropriate colleague is an essential part of the way in which individual, departmental and other needs may be reflected on and planned for. This has been dealt with separately above, in relation to appraisal. The actual approaches to needs assessment, which might be reported in the appraisal meeting, are now presented in the following six groups:

The clinician’s own experience in direct patient care

Interactions within the clinical team and department

Non-clinical activities

Formal approaches to audit and risk assessment

Specific activities directed at needs assessment

Peer review.

These methods of needs assessment are listed in Appendix 3.

NEEDS ASSESSMENT BASED ON THE CLINICIAN’S OWN EXPERIENCES IN DIRECT PATIENT CARE

TYPE | METHOD |

The clinician’s own experiences in direct patient care | Blind spots Clinically-generated unknowns Competence standards Diaries Difficulties arising in practice Innovations in practice Knowledgeable patients Mistakes Other disciplines Patients’ complaints and feedback Post-mortems and the clinico-pathological conference (CPC) The patient’s unmet needs and the doctor’s educational needs (PuNs and DENs) Reflection on practical experience

|

Blind spots

Often, long and detailed reflection on practice is not required to know that some further education or training might be in order. Technical and knowledge deficiencies, in particular, may suddenly and obviously be identified during the course of daily practice. These should be deliberately noted and plans for appropriate training made.

Clinically-generated unknowns

From time to time every doctor will encounter a clinical picture, reaction or process which is entirely unfamiliar. In such circumstances, the doctor must decide whether to refer the patient to another specialist or to find out about the observed phenomenon, or do both. In referring, it is likely that the doctor will learn about the entity from the colleague whose opinion is sought. There are many ways of dealing with such events and the choice is a matter of clinical judgment. The educational effect should be noted and recorded as a valid method of professional learning.

Competence standards

There are many worries that competence standards set a minimum level of performance that will limit people’s aspirations for excellence.25 Nonetheless, standards are necessary and so some societies, colleges and organisations h...