Chapter 1

The establishment of NICE

Peter Littlejohns

NICE is an independent organisation responsible for providing national guidance on promoting good health and preventing and treating ill health in England and Wales. It was established as a special health authority in 1999 to offer National Health Service (NHS) professionals advice on how to provide their patients with the highest attainable standards of care and to reduce variation in the quality of care. Specifically, NICE aims to speed the uptake of interventions that are both clinically and cost effective (i.e. that work and are value for money). It also aims to encourage more equitable access to healthcare, provide better and more rational use of available resources by focusing on the most cost-effective interventions, and encourage the creation and dissemination of new and innovative technologies.

Since its inception NICE has been controversial.1,2 This was inevitable because for the first time a national organisation was explicitly stating that the healthcare system could not afford all the interventions that could benefit individual patients. Treatments needed to be prioritised according to the extra value that they provided to patients compared with existing practice. The approach that NICE took was based on a number of key principles.

➤ All of its guidance should be based on the best available evidence.

➤ The process should be as open and transparent as possible.

➤ The process should be inclusive: any stakeholder likely to be affected by its guidance should be part of the development of that guidance, either by being a member of one of the independent advisory bodies or through participating in open consultations.

All NICE advisory bodies contain healthcare academics, professionals, industry representatives, patients and where appropriate, the general public. Most of NICE’s advisory bodies now meet in public. Over the years NICE has developed particular expertise in patient and public involvement. It has established a designated patient and public involvement programme and a Citizens Council, which consists of members of the public who consider the nature of social values underpinning NICE guidance.

Over the 10 years it has existed, NICE has been invited to take on a range of new responsibilities. A major development occurred in 2005 when its remit was expanded to include health promotion and disease prevention.3 This followed an independent review of policies to achieve cost-effective improvements in the health of the English population and reductions in health inequalities. The review was commissioned by the UK’s treasury department and resulted in a white paper on public health policy.4,5

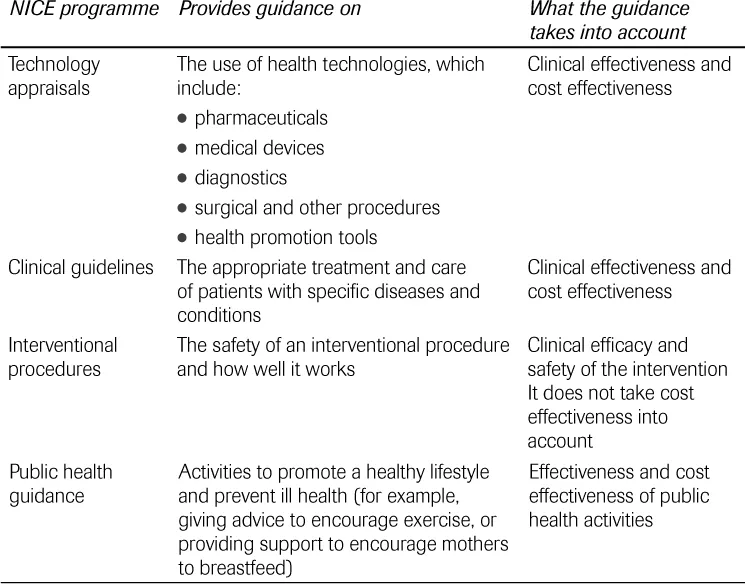

NICE currently has four programmes that produce guidance (see Table 1.1). These are: technology appraisals, clinical guidelines, interventional procedures and public health guidance. Most programmes take both effectiveness (how well an intervention works) and cost effectiveness (how well it works in relation to how much it costs) into account.

TABLE 1.1 NICE guidance programmes.

Currently, NICE has 311 full-time staff with an annual budget of £35 million. It has offices based in London and, since 2005, also in Manchester. However, its guidance development is supported through a series of directly commissioned National Collaborating Centres and university-based academic units funded through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the body responsible for funding NHS research in England. This means that more than 2000 individuals (excluding external stakeholders) are involved in developing guidance at any one time. Following a national review during 2007/08 to establish a 10-year vision of the NHS by Lord Darzi, the functions of NICE will expand further.6

NICE has now produced guidance in most fields of healthcare and public health. Although NICE does not have responsibility for ensuring that its guidance is put into practice it soon became apparent that more support for implementation in the NHS was required. In 2004 an implementation directorate was established to support guidance implementation through a series of education and liaison functions. Support tools (including costing templates) are now issued with each guidance document.

Controversial Decisions

While much of NICE guidance has been welcomed, it is inevitable that both the general and professional media concentrate on the controversial nature of those recommendations that limit access to cost-ineffective treatment. NICE guidance recommendations are rarely completely negative. However, they may recommend treatment for a more-targeted group of patients than is represented in the full licensed indications of a drug. For example in the field of oncology where decisions have generated the most consistent controversy, between 1999 and 2009 NICE made 76 decisions in 47 appraisals for cancer agents. A decision to not recommend for any licensed indication was made in only 13% of appraisals (10 decisions). In 46% of appraisals (35 decisions) the guidance recommended use in line with their licensed indications, and for 28% of appraisals (21 decisions) the recommendations were restricted to certain patient groups (usually on the basis of cost effectiveness). In 8% of appraisals (six decisions) recommendations were made for the drug to be used in a research setting only, and in 5% of appraisals (four decisions), industry declined to submit evidence.

Perhaps due in part to NICE’s continuing argument that cost effectiveness is determined by two factors, that is, if you cannot improve effectiveness then cost needs to be reduced, manufacturers have started to explore ways in which their drug can be made available in a cost-effective way to the NHS. These ‘access schemes’ have required negotiations with and approval of the Department of Health before being referred to NICE for consideration. The first cancer guidance incorporating this approach concerned bortezomib for multiple myeloma. A similar approach was taken with ranibizumab for the treatment of macular degeneration where industry pays for treatment after the initial 14 injections.

Since its inception NICE has maintained that efficiency in terms of cost effectiveness, and accounting for opportunity costs were key determinants of assessing value. However, other factors such as fairness and reducing health inequalities are also important. These other ‘values’ are encapsulated in the document Social Value Judgements: principles for the development of NICE guidance, first published in 2005 and further refined in the second edition published in 2008.7 This document forms the basis of NICE’s advice to its advisory bodies on how to apply social value judgements when making decisions. The eight social value principles were formulated through a series of workshops involving ethicists and moral philosophers as well as reports from the Citizens Council.

NICE uses the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) as the main health outcome measure. This unit combines both quantity (length) of life and health-related quality of life into a single measure of health gain. A review of guidance decisions during the first few years has indicated that NICE’s threshold for cost effectiveness lies in the range of £20 000 to £30 000 per QALY. However, NICE’s independent advisory bodies have always had latitude to recommend technologies for which the cost effectiveness is above the upper range, providing there is a strong case to do so.

In 2006 the Office of Fair Trading (the UK body responsible for ensuring that markets work for consumers) produced a report that suggested the existing scheme for pricing drugs in the UK was not beneficial to the NHS. It advocated a ‘value-based’ approach to pricing on the basis of assessments similar to those undertaken by NICE.8 In 2008 the Department of Health terminated the existing Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS) and negotiated a new process with the industry, which was agreed and published in December 2008.9 In the new PPRS agreement, NICE has a role in providing information on the cost effectiveness of new drugs. The single technology appraisal programme, introduced as a means of ensuring that NICE appraisals can be published as close to the licensing of new drugs as possible, will need to expand as a consequence.

Another major development relevant to NICE’s appraisal programme was the report by the Department of Health’s National Clinical Director for Cancer, Professor Mike Richards, in 2008.10 Following public concern, he was invited to undertake a review of the status of ongoing NHS treatments if patients decided to buy drugs that were not recommended by NICE or funded by their primary care trust (PCT) – so-called ‘top-up’ payments. The Department of Health accepted the recommendations of this report in their entirety. This meant that if patients wished to pay for treatments not approved by NICE or funded by their PCT they would no longer have to also pay for the rest of their NHS treatment. The acceptance of this principle was in part based on NICE being able to issue guidance on drugs close to their licensing.

Alongside the report by Professor Richards, NICE has been exploring methods to capture patients’ values on treatments that extend life in situations of very limited life expectance. These explorations have focused on drugs that are not cures but, nonetheless, extend life. In conjunction with the NIHR, NICE has previously commissioned a series of research projects to assess whether society would assign the same value to quality of life and life expectancy (measured as QALYs) under all circumstances. Citizens Council reports, as well as the commissioned research, suggest that this assumption may not fit in with society’s view and that society may well place greater importance on some circumstances, such as severe disease, or disease in children. While the methodological research suggests that ‘weighting’ should be considered, it does not provide a definitive list of what these circumstances should be or by how much. In January 2009 NICE issued further advice to the technology appraisal advisory bodies around their explorations of cost effectiveness of end-of-life interventions with consideration to this important issue.

As a public body NICE is subject to judicial review and despite the controversial nature of its guidance, it didn’t receive a legal challenge for the first eight years of its existence. In the last two years there have been three legal challenges. The results have, in general, supported NICE processes, although some changes have had to be made to the appraisal process to allow stakeholders to scrutinise the cost-effectiveness model. No guidance has been materially affected by the court’s decisions.

How Nice Manages Uncertainty

The UK has traditionally been internationally excellent in undertaking basic research but less skilled at translating that work into routine practice. To address this issue, Sir David Cooksey undertook a major review of UK health research in 2006. Sir Cooksey called for more collaboration between key stakeholders, including the Medical Research Council (MRC), NHS Research and Development, NICE and industry.11 Sir Cooksey proposed a series of actions to ensure that publicly-funded health research was carried out in the most effective and efficient way, resulting in a timely translation of research findings into health and economic benefits.

The most important recommendations from NICE’s perspective were recommendations for enhancing drug development and th...