![]()

Part I

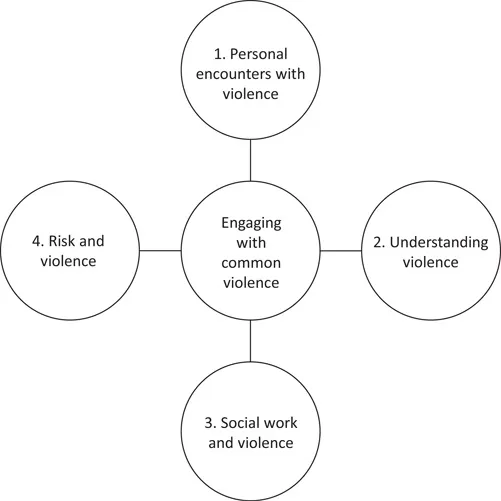

Engaging with common violence

![]()

Chapter 1

Personal encounters with violence

Introduction

In training, I sometimes ask the group of social workers to take a few moments to reflect silently on any violence inflicted on them within their relationships and family life, their wider community life or their work situations. I ask those who feel that they have never been on the receiving end of violent behaviour to put their hand up. No one to date has raised an arm. A small-scale piece of research took this a little further with a group of social work students who were asked to write about their own experiences as victims of the common violence referred to in the introduction. Their list included ‘armed robbery; the unlawful killing of a relative; sexual assault; childhood sexual abuse; neglect; rape and several episodes of domestic violence’ (Robbins 2014, p. 5).

This chapter will explore the impact of such encounters with violence. Each person’s experience of these will be unique, but needs to be dealt with, both personally and professionally. This is critical if we wish to help someone else address their use of violence. What we do not sort out within ourselves may well be projected onto others (O’Leary 2016). What follows includes an account of my own efforts to do so, as well as associated reflections that may be helpful to others.

Violence within families of origin and relationships

All of us will carry some psychic and emotional wounds arising from experiences within our families, or relationships. To varying degrees, each person will have been on the receiving end of actions that will have caused distress and upset. There is always a need for reconciliation and forgiveness to get back on track and this is what often happens. Family and relationship breakdown can also cause deep and lasting hurt that cannot be minimised.

However, the focus in this section is on those who have gone through serious physical, emotional, sexual or other devastating abuses of power. I was fortunate that in my early family life and relationships, the foundation of trust, love and security remained in place. In many ways, I was naïve about such aspects of life. It was only over time, and through listening to the experiences of those on the receiving end of abuse, that I started to become more aware of and learn about the betrayal and emotional devastation caused by violence within close intimate relationships. My saddest and most traumatic memories from practice are from people whose lives were destroyed by the abuse they suffered.

As the study referred to above suggests, and confirmed by the staggering levels of this violence outlined in Chapter 2, there is every reason to believe that the experience of abuse is a reality in the lives of a significant number of social workers. Is there a danger that, for those who have endured such a legacy, it may ‘leak out’ and influence how they may engage professionally with those who have perpetrated such behaviours or other forms of violence? I have witnessed harsh judgements, disdain, apprehension and fear from social workers engaging with those who have used violent behaviour. Do such unhelpful reactions sometimes relate to past experience of abuse? Was this possibly the case in relation to the behaviour of the social worker below?

Example 1 ‘The letter’

Amir left his war-torn country to move to a European city. Some five years later, aged 34, he met and began a relationship with Jane who was studying in the same city. Following the completion of her studies Jane returned to her family home and, despite lengthy separations, their relationship continued, and they had a child who lived with Jane in Northern Ireland. Following an incident shortly after the birth of the child, Amir was convicted of a domestic violence offence against Jane. He spent some time in prison in the European city. The couple subsequently reconciled, and they agreed that Amir should travel to Northern Ireland where they would live together as a family. Social services became aware of his conviction, and he and Jane were informed that he would only be allowed supervised contact with the child until a full assessment of their situation had been completed. This risk assessment will be returned to in Chapter 4.

Amir initially had no official status to live in Northern Ireland, and resided in a small, poorly maintained terraced house with several other men – all seeking asylum. He was barred from working or claiming benefits and had to live on £10 per week, relying on food banks to get enough to eat.

Amir was very anxious to see his child regularly and depended on travel warrants being sent to his address so that he could make the journey. On one occasion, I called to see him at his accommodation. When we found a quiet corner in the damp, poorly furnished house he showed me a torn-open envelope with the address of the house on it. He was upset and his first words to me were: ‘She never even put my name on the envelope. Someone else opened this and knows my business now. I’m no better than something she walks on.’ He continued in tears: ‘I know the way she looks at me, she thinks of me as some sort of monster!’ He didn’t accept my suggestion that it may have been a mistake. He was adamant that I should not raise the matter. The failure of the social worker to put his name on a letter sent to him spoke powerfully to Amir.

I never spoke with the social worker about this incident and I cannot be sure about the motivation. It may have been an entirely unintentional oversight. Alternatively, it may have reflected racial prejudice towards Amir. I do not know. However, I did sense a strong aversion towards Amir’s behaviour and towards him. I wondered if this may have had its roots in the social worker’s previous and personal traumatic experiences of control and abuse.

Of course, past abusive experiences will not automatically impact negatively upon practice. I have worked with and been inspired by colleagues who have dealt with such experiences, and indeed used them to work sensitively and compassionately in helping someone appreciate more fully the effects of violence on others. The importance of the contribution of practitioners to the work who are also survivors of domestic violence is now well recognised (Hague and Mullender 2006). They have been able to cope with deep psychological and emotional wounds, and in ways that have made them stronger and special (Biddulph 1997).

Violence within communities and society

Growing up in Belfast and Northern Ireland I encountered violence. As a child from the Nationalist, mainly Catholic community, I quickly became aware that my identity could sometimes put me at risk. I remember being attacked and then having to avoid certain areas on my way to and from school, and a growing sense of difference, hostility and conflict. As a teenager, my family home was attacked, forcing a move to a different part of the city. When I married, our first home was in a ‘mixed’ area of the city. Following the sectarian murders of several people living in the vicinity and attacks on several houses, including my own, I once again, as my parents had done 15 years previously, moved to a ‘safer’ area. My home, and those of my neighbours, was demolished. In their place was built the brick wall with the high fence on top (18 metres in height). This is the same wall referred to and shown in the introduction.1

Twenty years of my working life were spent within a context of communal, political and sectarian violence, within a mainly nationalist area in Belfast. Years of discrimination and neglect had resulted in it being one of the poorest and most socially deprived areas of the United Kingdom at that time. Social adversities were further compounded by the continuing armed conflict between paramilitary groups seeking a political change and unification of Ireland and the police and military forces of Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom. The main paramilitary group was the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), whose political representatives were Sinn Féin.2 My practice often took place within a context of regular outbursts of violence and an unrelenting political struggle for the hearts and minds of an impoverished community. This all-pervasive context of communal violence presented unexpected challenges to my practice.

Example 2 ‘The choice’

Thomas, one of the young people in the photograph I referred to in the introduction, had been placed on probation following his involvement in car theft and associated offences. He was 21 at the time. As his probation officer I had a good relationship with him, but was making little impact in persuading him to change his behaviour. His offending caused distress to the local community and also saw him clashing with some members of the PIRA who had taken on a quasi-policing role. Their involvement in such a role reflected the general distrust towards and fear of the state police force at the time. I remember Thomas coming to the office and telling me in a rather matter-of-fact way that after ignoring several warnings from the PIRA he was to be ‘nutted’ (that is, shot in the head). However, he had been given two alternatives, either to leave the country or choose to be shot in both ankles, knees and feet as a ‘final chance’. He did not want to leave his home, so his choice was stark – ‘one in the head or six’. Although as a probation officer I was not able to engage directly with the PIRA, I had the threat confirmed through a community group who mediated between statutory and illegal organisations. I was shocked when he told me that he had already arranged a time and meeting place for the punishment shooting, and that he would be unable to keep our weekly appointments for a while, as he expected to be in hospital. Sadly, such barbaric ‘punishments’ carried out by various paramilitary groupings continue to this day.

Many social workers across the world live and work in dangerous war-torn or conflict-ridden areas and in communities beset with inequalities and violence. Like myself, they will probably never fully understand how living through such events has shaped them. They, and I, have had to find our own ways to process and come to terms with these experiences. The main coping tactic for myself and other social workers within the Northern Ireland conflict was probably one of avoidance. We steered away from all aspects of the ongoing ‘war’, disengaging from analyses of politics, power and conflict, and finding a ‘non-political’ and ‘non-sectarian’ approach through the communal conflict. We found that often the safest approach was ‘whatever you say, say nothing’!3 Of course, as we see below, this was not always without some difficulty.

Example 3 ‘Smiling assassins’

On one occasion, I was involved in a meeting between some probation staff and Sinn Féin community representatives. The purpose was to try to find alternatives to the punishment shootings and attacks on young people, like Thomas, who were alleged to be engaging in antisocial behaviour within the community. It was early on in the peace process and a significant number of people viewed Sinn Féin as ‘terrorists’ because of their close relationship with the PIRA – a view still held by some today. The meeting was cordial and polite. However, the difficulties experienced by some of those at the meeting became clear to me when I suggested shortly after to my manager that the meeting had gone reasonably well. Stern-faced and through gritted teeth, the manager almost spat out how hard it had been to sit across the table from those ‘smug smiling assassins’. Many social workers and their agencies have had to, and continue to, work through such feelings of fear, distrust and anger. Violence always leaves a legacy that is rarely fully overcome.

Social workers have consistently promoted positive messages of respect and reconciliation and, in particular, sought to support victims and communities devastated by the troubles. Reflecting the vision of the Chief Probation Officer at that time,4 the Belfast team in which I worked was proactive in engaging with various voluntary, neighbourhood and victim support bodies. Connections were made to ensure that despite being ‘agents of the state’ the team was able to operate throughout the most violent of times. One memorable example of innovative practice was the use of sporting activities and the creation of a board game by a colleague to help facilitate safer dialogue between young people from both of the main communities.5 Hopefully, someday, the full story of all the aspects of positive social work practice throughout the troubles will be told. A forthcoming publication addresses this issue in listening to and exploring some of the stories and challenges from this period (Duffy et al. 2018).

Academic and social work agencies have continued, right up until the present time, to cooperate with victims’ groups in working with new generations of social work students. There is a genuine commitment to inform and sensitise the students to the traumatic ‘troubles’-related experiences that many of those who use social work services have gone through. It is no coincidence that the current Victims Commissioner is a social worker.6

Violence within professional and working lives

Much social work practice is at the interface of pain, poverty and powerlessness (Morrison 2008). Social workers across many settings may occasionally experience this playing out violently against themselves. I first experienced this as a residential social worker, a practice context that can be ambivalent, tempestuous, volatile and sometimes dangerous for children and staff (Howard 2012). I have seen some colleagues deeply impacted by violence and abuse at the hands of already traumatised young people. As indicated in the introduction, comprehensive guidance on how best to deal with these situations will not be provided here. However, as with the other experiences of violence explored in this chapter, they do need to be dealt with. It is critical that organisations support staff through such situations. This does not always happen.

Example 4 On the receiving end of violence

Mary was a committed and experienced practitioner who enjoyed building relationships and supporting young people in residential care. John was a 16-year-old young person who had been in the centre for several months. He had experienced a history of abuse and trauma. He has used violence towards some women in his life. On this occasion, he approached Mary who was standing with some other staff at the front door of the children’s home. ‘I’m going to cut your throat you fucking whore.’ was his opening remark to her; this was followed up with pointing and aggressive gesticulations and continuing verbal abuse as he approached her. Mary held her ground, asking him not to be offensive towards her. John became more threatening and a physical restraint was required by other staff. Mary was upset and distressed by the incident itself, but this was magnified when she was subsequently criticised and disciplined for not quickly withdrawing from the situation. To be fair, the managerial response may have reflected an organisation that was sincerely striving to work therapeutically and wanted to avoid the use of physical restraints and the possibility of re-traumatising a young person. However, not only should Mary have received much more support; the insistence on a ‘passive’ approach to the young person’s aggression was ultimately unsafe for him.

Th...