- 616 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

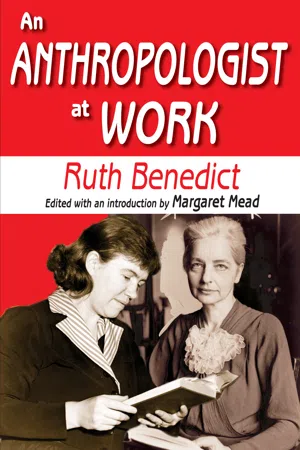

An Anthropologist at Work

About this book

An Anthropologist at Work is the product of a long collaboration between Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead. Mead, who was Benedict's student, colleague, and eventually her biographer, here has collected the bulk of Ruth Benedict's writings. This includes letters between these two seminal anthropologists, correspondence with Franz Boas (Benedict's teacher), Edward Sapir's poems, and notes from studies that Benedict had collected throughout her life. Since Benedict wrote little, Mead has fleshed out the narratives by adding background information on Benedict's life, work, and the cultural atmosphere of the time.Ruth Benedict formed her own view of the contribution of anthropology before the first steps were taken in the study of how individual human beings, with their given potentialities, came to embody their culture. In her later work, she came to accept and sometimes to use the work in culture and personality that depended as much upon social psychology as upon cultural anthropology. She came to recognize that society - made up of persons or organized in groups - was as important as a subject of study as the culture of a society.This volume, greatly enhanced by Mead's contributions, is a record of what was important to Benedict in her life and work. It is expertly ordered and assembled in a way that will be accessible to students and professionals alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

1

Search: 1920—1930

“I HAVEN’T strength of mind not to need a career,” Ruth Benedict used to say, with a rueful smile, during her first years in anthropology. And anthropology provided dignified busy work for a married woman without children who needed something significant to fill her time, but something which did not make too great claims on her dedication or her imagination. Although this attitude toward a career was never to disappear entirely, it was strongest at the beginning. She brought only one part of her life with her when, at the age of thirty-three, she began to do graduate work, and in her late thirties she could still write in one of her casually kept journal notes, “I gambled on having the strength to live two lives, one for myself and one for the world.”

Necessarily, any account of her life, either before she entered anthropology or afterwards, when told from any one point of view is unusually incomplete. She kept us all in separate rooms and moved from one to another with no one following to take notes. I visited her once at her summer home in New Hampshire, and I saw her husband three times. I never saw the family farm in the Shen-ango Valley. Before her death, I had met her mother and her sister only twice. Several of her closest friends I have never even seen. These all belonged in another part of life — as anthropology and poetry were separate worlds into which these others did not come in person.

I met her first in the autumn of 1922, when I was a senior at Barnard College. Professor Boas still taught a large undergraduate class there, and Ruth Benedict was the assistant who took us on trips to the American Museum of Natural History to illustrate the materials on the course. Although in the period between graduating from Vassar College in 1909 and marrying Stanley Benedict in 1914, she had taught English literature in a girls’ school, this was her first experience of college teaching. In the early weeks of that course, anthropology began to come alive for me. Professor Boas, with his great head and slight frail body, his face scarred from an old duel and one eye drooping from a facial paralysis, spoke with an authority and a distinction greater than I had ever met in a teacher. He believed in encouraging in his students the very kinds of behavior which his authoritative and uncompromising sense of what was right and just also tended to discourage. Characteristically, after a semester spent asking us rhetorical questions which we hardly ever ventured to answer—though I would write the answer down in my notebook and would glow with pleasure when it turned out to be right — he excused me and one other student from taking an examination, because of “helpful participation in classroom discussion.”

Marie Bloomfield1 and I set out to get acquainted with his assistant, “Mrs. Benedict,” while most of the class fretted against her inarticulate shyness and her habit of wearing always the same dress — and that not a very becoming one. Yet even for the two of us who were becoming excited by the material, the Museum classes were painful. After a particularly exciting — and halting — explanation of the model of the Sun Dance in the Plains Indian Hall, I asked for more references and was brushed aside with inexplicable asperity. When I persisted, the lecturer blushed scarlet and said she would give me something next time. This was a reprint of her own first published article, “The Vision in Plains Culture.”2 The fact of publication, having her name in print, mentioning that she had written anything were all almost too difficult to manage. Enthusiastic as Marie and I were about what we felt she was saying, when she invited us to the seminar at which she was to report on Human Nature and Conduct,3 we found her combination of shyness and inarticulateness devastating. It was years before she conquered this shyness and could speak with fluency and authority, and she was always a little surprised at herself when she succeeded and more than a little likely to add a touch of mischief to whatever she was saying successfully.

By the end of the first semester I was so enthusiastic and talked so much about the course on the campus that the registration doubled. Ruth Benedict’s vivid delight in the details of Northwest Coast art and of the Toda kinship system gave life to the clarity and order of Professor Boas’ presentation of man’s development through the ages. I could move from the sense of his grasp of the materials, through the sudden excitement of finding a picture of a reconstructed prehistoric man holding a bundle of firewood in his slightly too prehensile arms, to discussions with Ruth Benedict about both anthropology and poetry. She herself had just found Professor Boas and “sense,” and she conveyed to me a double feeling of urgency: the need to learn everything that he had to teach at once because this might be his last year of lecturing, and to rescue the beautiful, complex patterns that people had contrived for themselves to live in that were being irrevocably lost all over the world. So I began to attend all the graduate courses, little groups of five or six students under a professor who had no time for administrative red tape and who was perfectly willing to let an undergraduate go where an undergraduate wished.

I gradually learned how Ruth Benedict had found anthropology after seven years of childless marriage to a husband whose increasing distinction as a biochemist had been matched by his increasing withdrawal from any contacts except with his immediate laboratory assistants. None of the “causes” which had occupied her college generation had enlisted her interest. Woman’s suffrage, as a great issue, had bored her; education for women was a battle won, as far as she was concerned, in her mother’s day. Social work meant that somehow a life symbolized by “the suburbs” was to be promoted among the unfortunate. “But,” she would add hastily, “of course I don’t want people to live in slums.” The World War was for her an example of how ruthlessly man’s bright hopes could be destroyed — a feeling she expressed in the poem, “Rupert Brooke, 1914-1918”:4

Now God be thanked who took him at that hour,

Who let him die, flushed in an hour of dreaming.

Nothing forever shall have any power

To strip his bright election of its seeming.

He is most blest. There was great splendor dying

Then when our faith made all man’s hell a cleanness,

Then when our vision flashed like strong birds flying,

Before we had known victory and its meaning.

We are wise now and weary. Hopes he knew

Are perished utterly as a storm abated.

One mockery yet shall leap as flame wind-taken

Down dreadful years: unknowing what they do,

Our sons shall chant his words, and go elated,

Dying like him; like him with faith unshaken.

She had written poetry and under a pseudonym began to publish some poems, but no one was allowed to see her writing. “The poems were just saying ‘ouch’ because someone had stepped on one’s foot,” she would say. Community activities in the suburb of Douglas Manor, where she lived during the first years of her marriage, meant very little. She had tried teaching Sunday school but was dismissed when she gave her class the assignment of looking up Jesus in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The long summers in New Hampshire — for Stanley believed in long vacations5 — were delightful for the first two weeks and much too long thereafter. As she was physically strong and easily competent, housework in a summer cottage barely filled an hour. But the hours of depression must be masked; the day must be got through somehow until the depression lifted. In the winters she tried various expedients. She worked on a book of biographies of famous women, beginning with Mary Wollstonecraft.6 She spent one winter working quite hard at rhythmic dancing. Through Sophie Theis, a college friend, she worked as a volunteer for the State Charities Aid Association analyzing case histories. One after another, in these years, she watched her friends — the friends she had chosen for their special intensities — vanish into the maw of some completely accepted orthodoxy: Christian Science, high church Anglican missions, progressive education, psychoanalysis. And no child was bom to her.

When she first encountered anthropology, she was looking not for a real career but rather for some new expedient to get through the days which would be less meaningless than the others had proved to be. As Stanley had become increasingly intolerant of close neighbors and of urban living, they had moved to a little house in Bedford Hills, where he slept soundly despite the whistling trains. Psychoanalysis was just becoming known; the pressure, intensified through the years, to make each deviant person submit to it as a duty was fully embodied in advice given her by a college friend, who was well equipped with a knowledge of how depressed and desperate she often felt and who wrote to her:7

I am glad you are enjoying solitude in the woods, and reading. And I hope you are taking care of yourself, and playing and being outdoors. The trouble is, both you and Stanley have too much brain power, and you tend to work too hard. Don’t be old before your time. I hope you will move to the village and have a good time, and several love affairs, next year. Of course, there is no stake in life, only a series. That’s why living in the moment is so important. I shall always feel that you’d get a good deal out of analysis. You are, in many ways, a very suppressed person. You have built up two personalities, more or less consciously, a public and a private, and the strain is rather heavy. It isn’t that you can’t do it, but that it will wear you out to do it. And scholarship may become too great a retreat, much as it may benefit the world! However, any expression carries its wreckage, and intellectual achievement must be worth a good deal to you. Life is vacuous, and you cannot have the sense of utility every moment. . . .

In 1919, she decided to attend some lectures at the New School for Social Research, an institution which was still in a ferment of new ideas taught by brilliant people who were disqualified from teaching elsewhere by some act of social or political nonconformity. The young middle-aged, those who had been delayed or sidetracked in choosing a career, went there to explore, to taste the possibilities of kinds of learning about which they knew nothing. Among those teaching at the New School were Alexander Goldenweiser, the most picturesque of the generation of anthropologists who came to maturity before the first World War, and Elsie Clews Parsons, who had once written books of broad and provocative speculation — Social Rule and The Old Fashioned Woman and, under a male pseudonym (John Main), a book on ceremonial license.8

Goldenweiser, mercurial, excited by ideas about culture, but intolerant of the petty exactions of field work,9 was working on the first book by an American anthropologist which was to present cultures briefly as wholes. His Early Civilization10 appeared in the autumn of 1922. In his lectures the bold strokes, the vivid partial characterizations with which he sketched in “the red paint culture of Melanesia” or described the rise and fall of Gothic architecture in Europe, the magnificent flare that outshone the lack of detailed information caught the imagination of students, whom he treated as potential captives of his charm.

Goldenweiser interested both Ruth Benedict and Melville Hersko-vits, who entered anthropology from the New School at the same period. His book was the first one that undergraduates could read to get a sense of what a culture was, and he had a quick, imaginative response to the enthusiasm which his brilliance inspired in others. Ruth Benedict valued what she learned from him and writhed at his naive sense of self-importance, a quality for which she had little charity.11

Mrs. Parsons was lecturing out of her discovery of anthropology as a matter made up of the very careful assemblage and analysis of details, and her presentation contrasted sharply with Goldenweiser’s lazy brilliance. From her, students learned that anthr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Part V

- Part VI

- Chronology

- Notes

- Index of Personal Names

- Index of Subjects

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Anthropologist at Work by Ruth Benedict in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.