eBook - ePub

Scarcity and Growth

The Economics of Natural Resource Availability

This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this classic study, the authors assess the importance of technological change and resource substitution in support of their conclusion that resource scarcity did not increase in the Unites States during the period 1870 to 1957.Originally published in 1963

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Scarcity and Growth by Harold J. Barnett, Chandler Morse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Sustainable Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

Scarcity and Growth: A Summary View

MAN'S relationship to the natural environment, and nature's influence upon the course and quality of human life, are among the oldest topics of speculation of which we are aware. Myth, folktale, and fable; custom, institution, and law; philosophy, science, and technology— all, as far back as records extend, attest to an abiding interest in these concerns.

The Doctrine of Increasing Natural Resource Scarcity

The past two centuries—the period of industrial revolution, emergence of science, and population explosion—have witnessed a great broadening and deepening of interest in natural resources. An influential expression of this growing interest was that of British classical economics, early in the nineteenth century, with its doctrine that an inherently limited availability of natural resources sets an upper bound to economic growth and welfare. Later, there was the Conservation Movement in the United States, which took shape around the turn of the present century. Arising out of concern over natural resource scarcity and a consequent endeavor to formulate policies for the use of the extensive public domain, this movement provided broad, vigorous, and influential expression and political leadership. The interests, but not the vitality, of the Conservation Movement, survive in a vast current literature of scientists, engineers, social analysts, educators, journalists, businessmen, public officials, and adherents of a wide variety of academic disciplines. The occurrence and economic consequences of natural resource scarcity, and their social and policy implications, run like strong threads through the variegated fabric of contemporary public concern over natural resources. The doctrine of increasing scarcity and its effects has achieved remarkable viability.

The classical economists—particularly Malthus, Ricardo, and Mill —predicted that scarcity of natural resources would lead to eventually diminishing social returns to economic effort, with retardation and eventual cessation of economic growth. Indeed, classical economic theory acquired its essential character, and for economics its reputation as the "dismal science," from this basic premise. In a somewhat different formulation, the scarcity idea also entered the theory of natural selection when Darwin, acknowledging a debt to Malthus, saw competition for limited means of survival as the determinant of biological evolution.

The Conservation Movement accepted the scarcity premise as valid for an unregulated private enterprise society. But, rejecting laissez faire, at least so far as activities connected with natural resources were concerned, they believed that the trend of social welfare over time could be influenced by the extent to which men conserved and managed resources with an eye to the welfare of future generations. The leaders of the Conservation Movement proposed that society, taking thought for the consequences of its actions, should forestall the effects of increasing scarcity by employing criteria of physical and administrative—not economic—efficiency. They argued that government intervention could improve on the untrammeled processes of private decision making with respect to natural resources, and that public policies should be devised with this end in view. Their willingness to employ public power as a check on business freedom, signifying as it did a certain disillusionment with the principles of laissez faire, made the Conservation Movement something of a catch-all for interventionist ideas of all kinds. This helps to explain its many-sided character. But the core of the Movement was concern for the effect of natural resources, and especially natural resource policy and administration, on the trend of social welfare in a world subject to increasing resource scarcity.

Our principal concern is with economic doctrines of increasing natural resource scarcity and diminishing returns, and their relevance in the modern world. This reflects a professional bias, but also a conviction that serious consideration of the social, and more qualitative, aspects of the natural resource problem must be secondary—that is, must follow understanding of the more quantitative economic aspects. For, if growth and welfare are inescapably subject to an economic law of diminishing returns, the necessary social policies and the moral and human implications are surely different than if they are not. Alternatively, if there is reason to believe that man's ingenuity and wisdom offer opportunities to avoid natural resource scarcity and its effects, then the means for such escapes and their moral and human implications become the center of attention.

The problem we treat, it will be apparent, lies in the realm of historical growth economics, not of static efficiency economics. The latter enters our analysis on occasion, but only in a subsidiary fashion. Our framework is that of the classical economists in their theorizing about the trend of output per capita over the long term. Our main effort, therefore, is directed to a thorough examination of the conceptual and empirical foundations of the doctrine of increasing natural resource scarcity and its effects. Part II conducts this inquiry in a classical framework of unchanging sociotechnical conditions. Part III admits sociotechnical change into the analysis.

A World Without Progress

We take as our starting point for examination of scarcity doctrine a resource situation which we call "Utopian." In this hypothetical situation, natural resources are freely available without limit and with no change in quality—they do not retard growth. The social production process is one of constant returns to scale. Technological and social progress are ruled out. Under these conditions, returns per unit of input do not diminish. The labor-capital cost of a unit of output remains constant as population (labor) increases and capital accumulates. Nor is growth explosive; the rates of growth of labor and capital through time are taken as predetermined, and resources are used only up to the point at which output is a maximum for the given amounts of the complementary inputs. Hence, some natural resources remain unused, though freely available, until the growth process provides the population and capital accumulation required to make them productive. The time shape of the growth path is determined by the rates of growth of labor and capital; in the sense that natural resource availability is unlimited, natural resources exert no influence on the rate or shape of growth.

The Malthusian and Ricardian versions of scarcity are introduced in this basic model. For the former case, we assume that there is an absolute limit to resources, beyond which they cease to be available. The Malthusian case is thus like the Utopian up to the limit of resources. Thereafter, the increasing intensity of natural resource use entails a steady increase in labor-capital cost per unit of output.

For the Ricardian case, we assume that resources are unlimited in quantity, but not homogeneous. The Ricardian case rests on the proposition that, as growth proceeds, it draws upon incremental resources with physical or locational characteristics different from the resources already employed. But this, in itself, does not imply diminishing returns, for such alterations need not cause costs to increase steadily over time. An additional postulate, that society possesses both the knowledge and the will to use resources in order of declining economic quality—that is, in an order which results in increasing cost per unit of output—is needed.

The foregoing conditions (together with some additional specifications of detail) are sufficient to produce diminishing returns in both the Malthusian and Ricardian cases. These initial conditions, however, are only a precisely defined starting point for our analysis. Having been specified, they are systematically modified in ways that bring them closer to reality, and the effects on diminishing returns are observed.

The first step toward greater reality is to recognize that the stock of resources is not constant, even when discovery and technological progress are ruled out. Resources are depleted through use, destroyed by careless or unnecessary action, and otherwise extinguished. This has the effect of strengthening the case for diminishing returns, either by hastening the approach toward the Malthusian limit, or by reducing the available amounts of better resources faster than inferior resources in the Ricardian case.

A second modification of the original conditions is to recognize that social output consists of many products, that natural resources are exceedingly varied, and that labor and capital inputs differ widely in kind and quality. Consequently, as differential resource scarcities lead to changes in relative costs, there are opportunities to make economically rational substitutions that will ameliorate and, in some cases, even forestall the appearance of diminishing returns. Substitutions that ameliorate resource extinction—increased recovery and use of scrap, for example—also are possible. Substitution possibilities are increased as the production process becomes more complex, and are more likely to be effective if decisions concerning production are guided by economic rationality. They, therefore, are more important in advanced industrial countries than in less developed areas.

Third, we observe that the structural characteristics of a society can have an important bearing on the prospects for diminishing returns. If capital grows at a faster rate than labor, as it has in the industrialized countries, output per unit of labor (or even per unit of labor plus capital) will not necessarily fall merely because the input of natural resources cannot be increased, or because the economic quality of resources declines. More needs to be specified about the character of the social production process when the ratio of capital to labor is variable. Similarly, if the social production process yields increasing returns to scale during long-term growth—and it is not legitimate simply to presume that it cannot—there can be no assurance that a postulated increase in natural resource scarcity will produce diminishing returns. More information is needed concerning the relative strengths of the opposing forces. Furthermore, it is clear that the composition of output changes as output per capita increases. To the extent that this takes the form of a substitution of resource-light goods and services for those that make relatively heavy drafts on the resource base, this also ameliorates the force of increasing resource scarcity.

A fourth modification concerns the requirement of the Ricardian hypothesis that resources be used in order of declining economic quality. Even under the assumption of constant technology, it is rather much to expect that society will never be surprised by discoveries of hitherto unknown resources, especially as the growth of population carries men into regions not previously settled or systematically explored. Moreover, the growth and spread of population, by altering the location of resources relative to markets, will modify the order of economic use, possibly to the extent of reducing current costs below those prevalent at an earlier time. Also, a concern for the future sometimes leads to the adoption of public policies and institutional arrangements calculated to force inferior resources to be used before superior ones. Then, there is the circumstance that certain types of resources occur in broad plateaus so that costs remain approximately constant for extended periods of growth instead of increasing as required by the hypothesis. And, finally, there is the possibility that ecological unbalance—a concern of the American Conservationists—creates, as well as destroys, resources, and that the gain, as in the case of river valleys and deltas, may be greater than the loss.

None of the foregoing modifications of our initial conditions does material violence to the more general tenets of classical economic theory. Even so, doubts are raised concerning the certainty that natural resource scarcity and diminishing returns will occur in a growing, yet essentially classical, world. Questions arise concerning (1) the validity and significance of the Malthusian and Ricardian hypotheses of increasing natural resource scarcity, and (2) the probability that increasing scarcity, if present, will lead to diminishing returns in the social production process as a whole.

Malthusian scarcity, no doubt, has characterized many relatively primitive societies which possessed limited knowledge and skill. They not only failed to develop cultural taboos which stabilized population but also were able to extract only a small proportion of the services available in their natural environment. Thus, the limits of their resources were quickly reached. But such societies would also have to be relatively isolated, for otherwise cultural diffusion, migration, and interregional trade would offer the possibility of progressive extension of the resource limit. Under primitive conditions of isolation a relevant question is whether it is the limited availability of natural resources or the limited stock of knowledge that produces diminishing returns and inhibits economic growth.

The Ricardian hypothesis of declining economic quality of resources appears to us to be broadly relevant in a world of sociotechnical constancy. It cannot be presumed to operate with certainty and continuity, yet a tendency to recurrent upward movement in the cost of output of the extractive sector would seem more probable than a constant or declining trend. During selected historical phases of growth, however, the hypothesis could be invalid.

To recognize the probable occurrence of increasing resource scarcity is not to say that diminishing returns in social output are equally likely. Substitutions, increases in the ratio of capital to labor, and perhaps the realization of economies of scale in the social production process as a whole—all weaken the effect of increasing scarcity. The unit cost of aggregate social output, therefore, may remain constant or decrease even if the unit cost of extractive output rises continuously. Acknowledgment of the probable validity of the scarcity hypothesis in a classical world thus does not imply belief in the necessary occurrence of diminishing returns, especially for complex and flexible industrial societies.

Resources in a Progressive World

The assumption of sociotechnical constancy, to which we adhere throughout the analysis of Part II, is particularly unrealistic. Accordingly, this constraint is removed in Part III. But it then becomes virtually impossible to postulate a realistic set of conditions that would yield either generally increasing natural resource scarcity or diminishing returns in the social production process as a whole.

Recognition of the possibility of technological progress clearly cuts the ground from under the concept of Malthusian scarcity. Resources can only be defined in terms of known technology. Half a century ago the air was for breathing and burning; now it is also a natural resource of the chemical industry. Two decades ago Vermont granite was only building and tombstone material; now it is a potential fuel, each ton of which has a usable energy content (uranium) equal to 150 tons of coal. The notion of an absolute limit to natural resource availability is untenable when the definition of resources changes drastically and unpredictably over time.

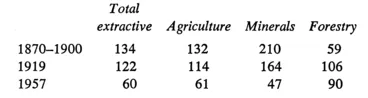

What technological progress does to the Ricardian scarcity hypothesis is less clear. We take account of two possibilities. One—which we call the strong hypothesis—is that the economic quality of resources undergoes decline despite the occurrence of technological progress. We cannot, unfortunately, test this hypothesis directly by measuring changes in the economic quality of resources—that is, in natural resource scarcity. However, we can measure changes in the cost of extractive output, an imperfect but reasonably acceptable stand-in for natural resources themselves. When this is done for the United States for the period 1870-1957, the indexes (1929 = 100) of labor-capital input per unit of extractive output1 are as follows:

The evidence mainly shows increasing, not diminishing, returns. The cost per unit of total extractive product fell by half during the period. Of agriculture and minerals—the two major components, which account for 90 per cent of the total—the latter fell even more. Only forestry gives evidence of diminishing returns; cost per unit of product rose from the Civil War to World War I. But since World War I, when an aggravation of scarcity due to further economic growth might have been expected, diminishing returns have given way to approximately constant (or slightly increasing) returns.

On the whole, our strong hypothesis of natural resource scarcity fails. True, the increase in the absolute cost of forest products can be taken as evidence tending to confirm the validity of the Ricardian hypothesis in this particular sector. During the period up to 1919, the exhaustion of the better and more accessible stands of trees led to increasing costs. In the subsequent three decades, however, the rise in costs had begun to produce three effects: an introduction of cost-reducing innovations, conversion of wood wastes into usable products, and a shift to wood substitutes. The first and second of these contributed primarily to the observed stabilization in unit costs; the third helped to moderate the effect of the previous rise in costs on the rest of the economy.

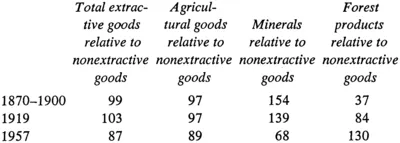

Our second—and weaker—formulation of the Ricardian hypothesis is that, in the extractive sector, the decline in resource quality will partly nullify the effect of economy-wide technological advance; and that costs of a unit of extractive goods will, therefore, rise relative to unit costs of nonextractive goods. The evidence—again for the United States, 1870-1957, and using indexes (1929 = 100) of labor-capital input per unit of output2 —is as follows:

Increase in natural resource scarcity should, according to the weak hypothesis, prevent the cost of extractive output from falling as much as that of nonextractive output. But, again with the exception of forestry, this did not occur. Relative unit costs of total extractive goods, and of agricultural goods, have been consta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Contents

- 1. SCARCITY AND GROWTH: A SUMMARY VIEW

- PART I. THE DOCTRINE OF INCREASING RESOURCE SCARCITY

- PART II. GROWTH AND INCREASING SCARCITY WITHOUT PROGRESS

- PART III. RESOURCES IN A PROGRESSIVE WORLD

- PART IV. WELFARE IN A PROGRESSIVE WORLD

- APPENDIX A. GRAPHIC SUPPLEMENT

- APPENDIX B. NOTE ON STATISTICS

- INDEX