![]()

PART I

In the Village

![]()

Chapter 1

Male and Female Farming Systems

A main characteristic of economic development is the progress towards an increasingly intricate pattern of labour specialization. In communities at the earliest stages of development, practically all goods and services are produced and consumed within the family group, but with economic development more and more people become specialized in particular tasks and the economic autarky of the family group is superseded by the exchange of goods and services.

But even at the most primitive stages of family autarky there is some division of labour within the family, the main criteria for the division being that of age and sex. Some particularly light tasks, such as guarding domestic animals or scaring away wild animals from the crops, are usually left to children or old persons; certain other tasks are performed only by women, while some tasks are the exclusive responsibility of adult men.

Both in primitive and in more developed communities, the traditional division of labour within the farm family is usually considered ‘natural’ in the sense of being obviously and originally imposed by the sex difference itself. But while the members of any given community may think that their particular division of labour between the sexes is the ‘natural’ one, because it has undergone little or no change for generations, other communities may have completely different ways of dividing the burden of work among the sexes, and they too may find their ways just as ‘natural’.

Many social anthropologists and other scientific observers of human communities have emphasized the similarities in the sex roles in various communities. One very distinguished anthropologist, Margaret Mead, in her book Male and Female, gives this summary description of the sex roles: ‘The home shared by a man or men and female partners, into which men bring the food and women prepare it, is the basic common picture the world over. But this picture can be modified, and the modifications provide proof that the pattern itself is not something deeply biological’.1

It is surprising that Margaret Mead, with her extensive and intensive personal experience of primitive communities throughout the world, should venture upon such a dubious generalization. She is right in describing the preparation of food as a monopoly for women in nearly all communities, but the surmise that the provision of food is a man’s prerogative is unwarranted. In fact, an important distinction can be made between two kinds or patterns of subsistence agriculture: one in which food production is taken care of by women, with little help from men, and one where food is produced by the men with relatively little help from women. As a convenient terminology I propose to denote these two systems as the male and the female systems of farming.

The position of women differs in many basic features in these two community groups. Therefore a study of the role of women in economic development may conveniently begin with an examination of women’s tasks in agricultural production in various parts of the underdeveloped regions of the world.

THE DIVISION OF LABOUR WITHIN AFRICAN AGRICULTURE

Africa is the region of female farming par excellence. In many African tribes, nearly all the tasks connected with food production continue to be left to women. In most of these tribal communities, the agricultural system is that of shifting cultivation: small pieces of land are cultivated for a few years only, until the natural fertility of the soil diminishes. When that happens, i.e. when crop yields decline, the field is abandoned and another plot is taken under cultivation. In this type of agriculture it is necessary to prepare some new plots every year for cultivation by felling trees or removing bush or grass cover. Tree felling is nearly always done by men, most often by young boys of 15 to 18 years, but to women fall all the subsequent operations: the removal and burning of the felled trees; the sowing or planting in the ashes; the weeding of the crop; the harvesting and carrying in the crop for storing or immediate consumption.

Of course, there are exceptions to this general rule. In some African communities with shifting cultivation, the women have some help from the men beyond the felling of trees. For instance, men may hoe the land or take part in the preparatory hoeing before the crops are planted, but even with such help the bulk of the work with the food crops is done by women. In some other tribes, most of the field work is done by the men. Thus, we may identify three main systems of subsistence farming in Africa according to whether the field work is done almost exclusively by women, predominantly by women, and predominantly by men.

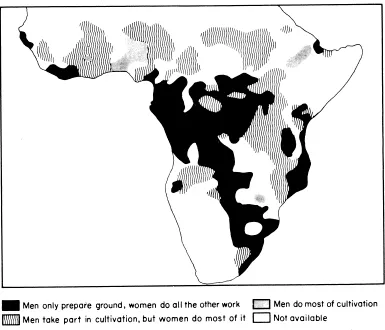

The relative importance in the African setting of these three patterns can be gauged from Figure 1. This map was prepared forty years ago by H. Baumann, a German expert on African subsistence farming. It appears that forty years ago female farming with no male help except for the felling of trees predominated in the whole of the Congo region, in large parts of South East and East Africa and in parts of West Africa. Female farming was far more widespread than systems of male farming and it also seems to have been more widespread than systems of predominantly female farming with some help from males in cultivation; this latter type of farming was characteristic of the region immediately south of the Sahara.

Farming systems which are not based on scientific methods and with no modern industrial input are usually described as ‘traditional’. It is widely but mistakenly assumed that such ‘traditional’ systems are necessarily passed on from one generation to the next without ever undergoing changes either in techniques or in the division of labour between the sexes. In historic times, tribes with female farming systems have been known to change over to male systems, and—less frequently—tribes with male farming systems have been known to adopt a female system of farming.2

Changes in the division of labour between men and women seem usually to have been related to changes in population density and in farming techniques. For one reason or other, the tribe may have migrated to another region, or local conditions for agriculture may have changed in the region where the tribe used to live. It might be, for instance, that the forest cover was disappearing as the density of population increased, so that the land had to be cultivated more intensively, with shorter periods of rest.

Figure 1 Areas of Female and Male Farming in Africa, Around 1930

With the gradual disappearance of the tree cover, the men’s tasks of felling must decline, as must the opportunities for hunting—another decidedly male form of work. On the other hand, with increasing population density new forest areas become scarce. As the fertility of the old ones diminishes, so will the soil need more careful preparation before it is planted, to offset less frequent periods of lying fallow. In such cases it may be necessary for men to help with the hoeing, or even to take over this operation completely from the women; a predominantly female farming system can thus change to one where the two sexes share more equally the burden of field work. Sometimes the increasing population pressure may induce the men to emigrate from the region in search of wage labour elsewhere. In this case of male depletion the women may have to take over some operations previously performed by men. Many such changes have taken place in various parts of Africa during the rapid growth of population in recent times.

Before the European conquest of Africa, felling, hunting and warfare were the chief occupations of men in the regions of female farming. Gradually, as felling and hunting became less important and inter-tribal warfare was prevented by European domination, little remained for the men to do. The Europeans, accustomed to the male farming systems of their home countries, looked with little sympathy on this unfamiliar distribution of the work load between the sexes and understandably, the concept of the ‘lazy African men’ was firmly fixed in the minds of settlers and administrators. European extension agents in many parts of Africa tried to induce the under-employed male villagers to cultivate commercial crops for export to Europe, and the system of colonial taxation by poll tax on the households was used as a means to force the Africans to produce cash crops. These were at least partly cultivated by the men, and the sex distribution of agricultural work was thus to some extent modified on the lines encouraged by the Europeans. In many other cases, however, European penetration in Africa resulted in women enlarging their part in agricultural work in the villages, because both colonial officers and white settlers recruited unmarried males for work, voluntary or forced, in road building or other heavy constructional work, in mines and on plantations.

As a result of all these changes, the present pattern of sex roles in African agriculture is more diversified than the one which gave rise to the European concept of the ‘lazy African men’. Therefore, the picture presented by Baumann’s map of the sex distribution of work for food production must be broadened and brought up to date to take into account the introduction of cash crops and the changes in the sex proportions in African villages brought about by male migrations.

The available data, although insufficient for drawing up a picture for the whole of Africa, gives very useful information about male and female work input in African farming in a number of local case studies. Sometimes these cover some hundred families selected by accepted sampling methods and representative ...