eBook - ePub

A Practical Guide to Academic Research

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Practical Guide to Academic Research

About this book

Covering all aspects of research methodology, this research tool also deals with planning issues and self-management techniques needed by the researcher. It contains information on data analysis and advice for staff members needing support from their institutions to pursue research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Planning a Research Project

There are a variety of reasons why people decide to carry out a piece of research. For many it is the need (or desire) to obtain a higher degree as most universities require some sort of research project, even with so called ‘taught’ masters and doctorates. In other cases individuals, teams or organizations may need to know how effective their activities are and what can be done to improve them. In such instances the research carried out will probably be ‘applied’ research.

The wide variety of situations and issues requires researchers to be familiar with a fairly wide range of methodologies. Research may be a piece of in-depth work within one organization or it may survey a range of institutions in a more comparative way. The research may be a qualitative piece of work or it may make much use of quantitative data and statistical methods. There is no set ‘standard’ format for a piece of research. It really depends upon the purpose for which it was devised.

Given these concerns, one of the essential abilities of any researcher is that of making focused decisions about the research. There is no one route to a particular conclusion, it is up to a researcher to decide where they wish to go and how they are going to get there.

PLANNING THE PHASES OF A PROJECT

Probably one of the first tasks the researcher will have to face when starting a project is the management of their time. Conducting research takes time (a minimum of 12–15 hours per week), so what is going to be given up in order to find time for the research?

ACTIVITY

Write down a list of social activities that you were involved in last week and then place them in order of importance.

Against each activity, write down how much time you spent on it, and consider where you can find time to carry out the research. Which activities in your list will need to be curtailed in order to provide this time?

It is also very important to routinize the research by allocating a set time and place in order to carry out the work. This at least enables researchers to feel healthily guilty if they choose not to work on the project at a particular time!

Most of those involved in research say that units of at least a whole day are preferable to allocating, say, a period of three hours to the research. Even better is if one can allocate longer periods at a time. This will give ‘real’ time for working and writing and the reflection so essential to the research process. Of course, this is not always easy. Often one has to settle for much shorter periods of time, but this is definitely second best.

The way in which time needs to be allocated is largely determined by the type of research that is being conducted. Work that is heavily dependent on libraries and archives tends to make different time demands from field work.

One of the most important jobs in planning a piece of research is to list and schedule all the tasks that are going to have to be undertaken.

ACTIVITY

Imagine that you have the task of conducting a traffic census outside your place of work and then preparing a report. Indicate the tasks involved in carrying out this assignment.

Once a complete list of tasks has been developed the next job is to place an approximate period of time against each task and schedule the list into a logical, sequential order. The technique of doing this is called Critical Path (or PERT – programme evaluation and review technique) Analysis and is described in Howard and Sharpe (1983).

ACTIVITY

Take the tasks listed above for carrying out the traffic census and:

1. put an approximate time against each one to indicate how long it will take

2. put the tasks in a logical order, indicating which tasks need to be carried out first.

You now start to obtain a picture of your project.

Finally, the above schedule must be converted into a calendar. Some will start with the final date by which they have to have their report or thesis prepared, others start with the here and now and then work forward. Whichever way is chosen, this calendar will become the master plan for conducting the research. It is obviously not inviolate -modifications may need to be made from time to time – but at the very least it will provide a yardstick against which to measure the progress of the project. Be fairly generous with time-scales, however, for various problems and slippage are likely to occur. Don't be too ambitious.

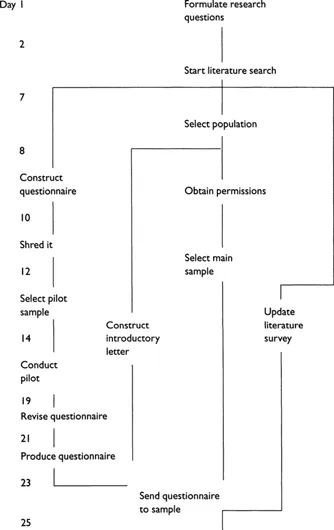

Figure 1.1 is an example of part of a typical critical path diagram, which illustrates how scheduling can be done. The figure represents the early part of a research project in which a questionnaire will be developed and then used.

Having allocated time and produced a schedule for the research, the next task is to develop a more detailed plan, describing the actual research methodology in a little more detail.

THE ROLE OF THE RESEARCH QUESTION

A suitable starting point can be a research question. A research question is a way of explaining as sharply and as pithily as possible to yourself exactly what you are going to research and what you wish to find out. Sometimes this may simply be in the form of a null hypothesis.

A null hypothesis is an assumption of a neutral (non-causal or interactive) relationship between two items. For example, one might wish to examine if there is any difference between rural and urban children in their interest towards biology. The null hypothesis might therefore be:

There is no difference between urban and rural children in terms of their interest in biology.

Figure 1.1 A typical critical path

The researchers would then have to develop a suitable ‘scale of interest’, sample equivalent groups of urban and rural children and see if there is any difference.

A null hypothesis of the type described above is often not suitable in the social sciences because one rarely has exactly comparable groups of the type suggested. Sometimes the research statement can be framed as a more general ‘working hypothesis’, but one will probably find few applications for such a strategy. More usually social science researchers are in a much more complex situation, where a research question will prove more suitable.

In general research questions should be positive statements which are capable of being proven or not proven. A statement which is a value judgement will not do, ie:

Geography is a more important subject than maths.

Similarly, a statement for which empirical evidence could not be obtained would not be suitable. An example of this might be:

Mathematics students in the twentieth century would score much higher in computer science examinations than would mathematics students of the nineteenth century.

A research question which presupposes the result would also not be appropriate, an example is:

I wish to show that my new reading curriculum is much better than the old one we used to use.

Research questions must therefore be framed in a positive manner, be value-neutral and be capable of being proven right or wrong on the basis of empirical evidence.

SOURCES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Research questions are likely to come from three sources.

1. Published books and articles. Very often such publications will contain ideas for further research which can be framed into research questions. Alternatively, existing research will often throw up research questions other than those it answers.

2. Similarly, all professionals and managers will develop or have a wealth of experience. Reflections on this experience can often give rise to questions that can be answered by carrying out a piece of research.

3. Finally, common-sense issues arising from one’s own expertise may be a good place to start.

FORMULATION OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The most important part of formulating a research question is to frame it at the correct level of abstraction.

A research question on organizational communication at differing levels of abstraction is illustrated below:

1. Is it possible to improve communication flow within this organiza- tion (in which I work)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Planning a Research Project

- 2. Obtaining Funding and Access to Conduct Research

- 3. Research Methodologies

- 4. Data Collection

- 5. The Presentation and Analysis of Data

- 6. Using Literature Sources

- 7. Research and Organizations

- 8. Quality Improvement and Research in Organizations

- 9. Reflections on the Research Process

- 10. The Computer and Research

- 11. Writing the Final Report and Getting the Work Published

- References

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Practical Guide to Academic Research by Graham Birley,Neil Moreland,Birley, Graham (Head, Education Research Unit, University of Wolverhampton),Moreland, Neil (Associate Dean, School of Education, University of Wolverhampton),Graham (Head Birley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.