This is a test

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emergent Warfare in Our Evolutionary Past

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Why do we fight? Have we always been fighting one another? This book examines the origins and development of human forms of organized violence from an anthropological and archaeological perspective. Kim and Kissel argue that human warfare is qualitatively different from forms of lethal, intergroup violence seen elsewhere in the natural world, and that its emergence is intimately connected to how humans evolved and to the emergence of human nature itself.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Emergent Warfare in Our Evolutionary Past by Nam C Kim, Marc Kissel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

PEERING INTO THE ABYSS

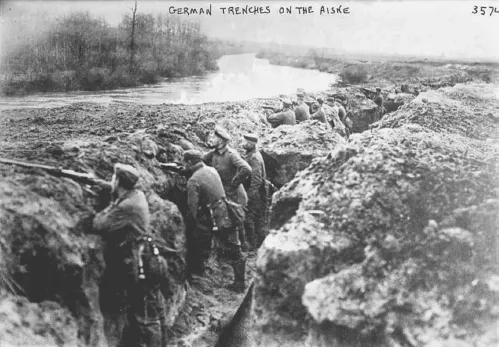

Why do we fight? Have we always been fighting one another? Warfare is a topic that generates much thought, opining, scholarship, and debate. And it is easy to see why. Take a look at any major newspaper’s front page and you are likely to see at least a headline or two about conflict or violence happening somewhere on the globe. Such conflicts are occurring at various scales and involve disparate collections of people. Chances are that you know someone that has been affected either directly or indirectly by warfare. In academia, researchers from various disciplinary backgrounds continue to investigate, and theorize about, the ubiquity of violence and warfare in the recent and contemporary world. For this book, any actions related to collective violence between politically distinct groups of people can be considered part of warfare, whether they involve nation-states, tribes, village communities, nomadic bands, or even terrorist organizations. By warfare, we are referring to myriad forms of organized violence, whether they are massed armies on a battlefield, revenge killings between smaller-scale societies, or intervillage raiding related to feuding communities. With this sort of inclusive definition, one not biased toward modern forms of war, we believe researchers are much better equipped to give the topic fuller scrutiny.

Increasingly, our collective knowledge has shown that forms of war have been part of humanity for a very long time. Signs of these behaviors appear as soon as our ancestors began recording ideas and messages on various media. Indisputable evidence comes to us from our earliest written records created several thousand years ago. But what can we see beyond that literary horizon? Material clues have been recovered hinting at violence occurring tens of thousands of years ago, maybe even hundreds of thousands of years ago. But, of course, violence is not warfare, especially if it is not part of some wider struggle, conflict, or clash between communities of people. Violence might be part of some interpersonal relationships and interactions within a community or society. Nonetheless, seeing so much violence around us today, along with hints of it in the past, begs the twin questions of how far back can we trace warfare, and how might the phenomenon have been connected to our earliest ancestral lineages in some evolutionary sense.

And so, this is a book about warfare and its beginnings. More specifically, it is about the origins of human forms of organized violence, or what we propose to call emergent warfare. As we will show, there are many divergent views about both the antiquity of warfare and its role in our evolution as a species. Our perspective overlaps with those of many others, but it is also a bit different, as it is by design informed by an anthropological perspective. For the category of human warfare, we see something qualitatively different from forms of lethal, intergroup violence seen elsewhere in the natural world. And so our concern here is to explore the onset of emergent warfare within our species, to see how various building blocks related to human biology and culture combined to set the stage for the earliest manifestations of warfare. Actually, that was the original intent of this book, but somewhere along the way, as we delved deeper into the research, we realized the story of emergent warfare was really a story within a story. It is one that needs to be told within a bigger purview. As we lost ourselves within the vast universe of evidence, case studies, and data from all over the world, we began to realize our perspective had to be broader, especially if we hope to answer some fundamental questions about “human” warfare. In the end, this is not simply a story about how, when, and why human warfare emerged, but is also a larger narrative about us, about humanity. In other words, the emergence of warfare is intimately connected to the emergence of human nature. And once we realized that the bigger story was our journey to becoming human, we then began to see the other half of the coin – namely that emergent warfare happened concurrently with what we might call emergent peacemaking abilities, or what we might call emergent peacefare. Hence, the real story is intimately linked to how we evolved ways to interact, how we pursue social strategies tied to both engaging in organized violence and ways to avoid and minimize its occurrences and consequences. As we will highlight, many scholars, philosophers, and other writers have emphasized either violent or peaceful behaviors in the story of human evolution, arguing how one or the other was a key driver, thus resulting in highly contentious debate. And oftentimes, some of these views were based on select categories or pieces of evidence and data. Our motivation with this book was to approach this set of questions by reviewing as much anthropological evidence as possible. Our resulting perspective is that it was a propensity for human sociality and cooperative behaviors that permitted warfare and peacefare to emerge, making them more outcomes than drivers of human evolution.

This book will provide the reader with both a starting point for answering basic questions about organized violence along with its relationship to our evolution as a species. We see this volume as a primer of sorts for all interested readers, from the uninitiated to the specialist. The amount of publications, research studies, and new datasets is growing at dizzying speeds, resulting in far more knowledge than we will be able to cover in this volume. However, we make an attempt here to capture a snapshot of the current state of research about the evolution of war, and to cover some of the main ideas researchers have published about this topic. As you will see, we firmly believe that the best way to approach this topic is to rely on an integrative, anthropological lens. It’s the best way to fully and robustly consider the wealth of data available that are relevant to reconstructing behaviors of our distant ancestors. Think of this book as a roadmap to understanding the evolution of war, sociality, cooperation, and conflict avoidance in humans, and what that tells us about human evolution more generally. On our journey through theories, ideas, and evidence, we will be taking the reader on a guided tour of the distant and recent pasts. While we will offer our thoughts and interpretations of the currently available evidence, the larger mission of this book is to give our readers a small window into the general landscape of current research that connects the earliest forms of collective violence with our pathways of both biological and cultural evolution. We endeavor to equip our readers with a familiarity of traditional, current, and future research concerning early human warfare as well as how we may have evolved ways to thrive in coexistence, developing innovative ways to avoid or mitigate conflict and organized violence. We hope, especially, to give those readers fairly new to this topic the means to be critical consumers for all of the fascinating research that continues to surface about emergent warfare.

Outfitting Ourselves for the Journey

Situated within general debates about the nature of violence in humanity, the beginnings of warfare in our evolutionary past become all the more salient. The origins of war and violence have interested people from many academic disciplines (see Levy and Thompson 2010; Pinker 2011; Shackelford and Weekes-Shackelford 2014; Smith 2007), but we argue that anthropology, which studies all aspects of humanity and our societies both past and present, gives us the best tools to tackle the topic. For us, the anthropological discipline encompasses important subfields that offer insights into this topic, including ethnography, bioanthropology, paleoanthropology, linguistics, and, of course, archaeology. While publications produced by non-anthropologists acknowledge and present anthropological data, many do so without comprehensively engaging the evidence, methods of data collection, and challenges in interpretation. As far as the deepest past is concerned, many non-anthropological studies present depictions based on uneven considerations of all available evidence. The material and fossil records have often been either underutilized or used in an unbalanced fashion by many researchers. Some read too much from scant data, while others tend to overly downplay the evidence. Unfortunately, there has been a tendency to oversimplify the past.

To truly understand human warfare, it is necessary to start with the earliest perceivable instances of what might be considered emergent warfare, and to engage all of the available data. What are the earliest expressions of what we would consider human forms of collective violence? When did they occur? What were they like? What became of them? How did they affect our cultural and biological evolution? Because our principal research question is intimately tied to the origins of human evolutionary behavior, the central research themes of this book must be addressed primarily through a disciplinary lens of anthropology.

Anthropologists are concerned with all aspects of people, their societies, and their cultures. This means looking carefully at all people through case studies of past and present societies, and, in doing so, simultaneously looking at people separated by space and time. We do this as a way to understand us, to gaze deeply at ourselves. As noted by Patty Jo Watson (1995: 690), “Anthropology is still the only human science all about humankind, from four million years ago to the present: Who are we? Where did we come from? What happened to us between origin and now?” The past and the present offer a mirror of sorts for us to confront and understand ourselves, where we have come from, and what the future holds. The causes and consequences of modern human variation have their roots in deep time. The archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnographic records thus constitute an important foundation for considering humanity’s overall course of change, and anthropological methods of data collection, interpretation, and theory building offer indispensable tools for appreciating humanity. Consequently, our approach in this volume relies on an integrative anthropological perspective, as we believe the discipline offers an important voice in larger debates outside of academic arenas. Indeed, we see a holistic anthropological approach as vital for giving us the most complete perspective on early warfare. Without question, this sort of research enterprise is impossible without fully marshaling the gamut of methodological approaches and frameworks of the anthropological discipline.

Anthropology has a varied and long history of engagement with questions of violence and warfare, and the origins and evolutionary arc of collective violence have been the focus of increased archaeological investigation in recent decades (Ferguson 2008, 2013a; Keegan 1993; Keeley 1996; Otterbein 2004). Of fundamental interest is whether or not forms of organized violence are universal for all people, both past and present, and a comprehensive consideration of this research focus necessitates a rich engagement with evidence from various anthropological subfields. According to McCall and Shields (2008: 2), recognizing interpersonal violence in the fossil and archaeological records of our early hominin history “is extremely important to modern theoretical perspectives on the nature of interpersonal violence.” We agree, and would say the same applies for studies of intergroup violence. As noted by many anthropologists, an “integrative” (Fuentes 2015) or ‘‘holistic’’ (see Harkin 2010) anthropology, one that pulls together information from across subfields, can offer powerfully informed perspectives on our species and the various ways in which our behaviors have taken expression in cultural patterning and forms. Anthropology is therefore well suited to contribute to questions about the evolutionary history of warfare in our species, allowing access into a variety of evidentiary sources. This diversity, in terms of research agendas, methodological approaches, and theoretical stances, has fostered a plurality in interpretations, and has already contributed to, and will continue to enrich, our understanding of warfare.

Beyond the Literary and Distant Horizons: Exploring Emergent Warfare and Emergent Peacefare

Warlike behaviors have been documented by humans for as long as writing has existed, and archaeological indications suggest an even deeper history for them. In our exploration of this deeper past, we are looking at emergent forms of warfare. To be clear, this book is not about why violence occurs in the natural world. Plenty of species fight their own (i.e., conspecific or intraspecific violence) and members of other species (interspecific violence). Aggression, competition, and violence are not rare in the animal kingdom. Depending on one’s perspective, then, warfare and participation in organized violence are not necessarily unique to humans. But, as we will argue, many of the ways in which humans (and possibly our earliest ancestors) perform (and have performed) organized violence are unique. Hence for this book, we are interested in the roots of human warfare and how it, in variant forms, might be related to our evolutionary past and what it might reveal about our earliest capacities to work together and form group identities.

Our unique abilities as a species allow us to think, socialize, and cooperate in much more complex ways than seen with other species. And while we argue that this has resulted in distinctly human forms of warfare that require people to organize in order to fight other groups, this complexity in cognition and behavior also applies to the ways in which humans have evolved to get along and to avoid and resolve conflict – to cooperate, and to construct and perform peace. A recent volume edited by anthropologist Douglas Fry (2013a) explores the connections between human nature, peace, and war, and we see this convergence of research topics to be very important for understanding humanity’s past and future with regards to war. Indeed, we propose that any examination of emergent warfare necessitates a consideration of emergent peacemaking. Furthermore, we submit that the emergence of all behaviors and cultural practices related to either phenomenon is intimately tied to “human nature” (see Barash 2013 and Sussman 2013). And when it comes to peace, we are not referring simply to an absence of war. Our view of peace is a bit more complicated than that. In a recent book, researcher Dane Smith (2010) uses the term “peacefare” when exploring US peace-building policies. Although we are dealing with peacemaking in far earlier contexts, we like Smith’s notion of peacefare (and hence have adopted it for our purposes) as it suggests peace as something requiring collaboration. Indeed, as we will highlight in Chapter Seven, some formulations of peace are not only culturally constructed, but require complex forms of social interaction and institutions, and perhaps even political mechanisms, in order to develop and maintain over time. With peace, we are talking about actions, beliefs, cultural practices, and institutions that are deliberately created and performed in order to promote stability and cooperation among people. These social patterns consist of cooperative strategies, social networks, recognition of specific kinds of ties between individuals and groups of people. In that sense, peace is neither simply the absence of war nor some default state of nature. Forms of peace are socially constructed and actively maintained – so when we refer to peace, we are usually thinking of it in terms of peacemaking. From that perspective, we might also surmise that people have been living in sophisticated and complex sorts of social organizations for quite a long time, even well before the advent of so-called complex societies and civilizations that supposedly emerged only in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- 1 Peering into the Abyss

- 2 Dropping into the Rabbit Hole

- 3 The Recent, the Ancient, and the Very Ancient Past

- 4 The Ice Age World

- 5 Insights from Genomic Research

- 6 The Onset of Human Variability and Emergent Warfare

- 7 The Durability of Peace

- 8 There and Back Again

- Index