![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

The word ‘medieval’, derived from ‘the Middle Ages’, that is, the period between Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance, only really has any meaning (how much is debatable) with reference to Europe. But what is Europe? The contributions in Part I address that question, directly or indirectly, from many different angles. First and foremost, European culture was based on that of Rome which in many ways incorporated that of Greece. The existence of the Roman Empire between the first century BC and the fifth century AD ensured that classical forms and norms were spread and rooted throughout much of geographical Europe. In, say, 400, urban civilisation, with its aqueducts, theatres, forums, temples, looked similar whether you were in Bordeaux or Brindisi, Tarragona or Thessaloniki. Roman citizens using the same law could make contracts that were standard in form, and equally valid, in London and Lyons, Nantes and Naples. Latin was the language of the military and of the educated in Cologne or Corinth, Seville or Syracuse. Surveyors and engineers worked to the same rule-books in Galicia and Calabria. Over all these aspects of social life brooded the Roman state, with its tax system, its armies, its vast public works.

Yet this neat picture of homogeneity is only part of the story. Regional differences remained fundamental, rooted as they were in geography and ecology. The economic integration of city and countryside, and the pervasive impact of human action on the landscape, were nowhere clearer than in the Po valley, the region that since the later sixth century, thanks to the arrival then of Lombards from the Danube area, has been called Lombardy. Settlement patterns there would change little between Roman times and the twentieth century. Contrast, though, the region’s political centrality to the Roman Empire, especially c.400 when the imperial capital was Milan, with its political fragmentation in the Middle Ages; and then again, contrast that fragmentation with the region’s economic centrality from the twelfth to the fifteenth century. Many other regions never displayed the standard, symmetrical, land divisions of the Po valley, or boasted its bustling commercial cities: Galicia and Brittany retained their own distinct Celtic languages and legal customs into modern times, the Tyrol and the Tuscan Appennines kept their distinctive forms of land-use. Beneath its smooth surface, the Roman Empire, especially towards its more mountainous spines and peripheral edges, was lumpily diverse. In the Middle Ages, with the superstructure of the imperial regime removed, that regional diversity became fascinatingly obvious, not least in the emergence from Latin of distinct Romance languages such as Occitan, Catalan and Provençal. Now, in the early twenty-first century, Europeans worry about the fading of local customs and centuries- (perhaps millennia-) old forms of land-use, and struggle to preserve (and reinvent) regional traditions.

Such differences at the level of whole provinces, say the divisions between Spain and France and Italy, crystallised in new political formations in the fifth and sixth centuries, with the establishment of kingdoms. Even though Charlemagne (as every continental school-boy and -girl knows) was crowned emperor on Christmas Day 800 and so revived a Roman Empire in the west, this was a mere ghost of the old, and never worked as an institutionalised unified state. For the most part, the medieval state was the kingdom: a new, distinctively medieval, unit of political power, with a new ideological basis in the bond between king and people and the territorial specificity of its own cult-sites and ritual centres. While it is certainly true that most modern European states have been busily fabricating ‘medieval’ traditions for themselves since at least the nineteenth century, not all traditions claiming medieval roots are bogus: in England, the legal system, for instance, and in France, the notion of national unity, are, in truth, medieval creations.

On the other hand, medieval kingdoms were untidy states. They claimed no monopoly on political power within their boundaries (though they did have clear boundaries), but instead accommodated multiple levels of relatively autonomous power – such as aristocratic territorial lordships, or regional elites whose collective ascendancy was institutionalised in assemblies – and discrete cells of power in the forms of towns privileged with rights of self-government. Power in medieval societies, in short, was layered and split, in ways that made them, functionally and conceptually, very different from the Roman Empire. For that matter, medieval layers and splits are distinct from modern ones, and hence not captured (hard as some historians have tried) by modern concepts of devolution and subsidiarity.

Within the Roman Empire, there was another kind of difference, on a much vaster scale than that between regions and provinces: the division between East and West. The formation of the empire had gummed Greek-speaking and Latin-speaking areas together, but could not make them cohere. The legacy of Hellenistic monarchy, that is, of Alexander the Great and his heirs, which predated Rome’s conquest of Greece and the eastern Mediterranean lands, and made its own amalgam of near-eastern and Greek cultures, proved remarkably durable. Empire penetrated the depths of political life in Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt as it never did in the landmass of Rome’s western provinces with their very different traditions of aristocratic ‘liberty’. Bi-lingualism in Greek and Latin was official in the Roman Empire – laws were issued in both languages, for instance – but in social practice people mostly used one or the other – or one of any number of other regional languages. Elites in Asia Minor or Egypt used Greek, in Spain and Gaul, Latin. The administrative division of the empire between East and West in the fourth and fifth centuries coincided with the period of political strain and eventual division in the West brought about by the immigration of ‘barbarians’ (as Roman writers called the Goths, Franks, Vandals, and others) and the formation of ‘barbarian’ kingdoms. After 476, there was no longer a western emperor at all. The establishment of a kingdom involved some degree of violent expropriation of the indigenous provincial populations but a much larger degree of cooperation and entente between indigenous elites and incoming ones. For example, the creation of a kingdom covering most of Gaul by Clovis, king of the Franks, and his followers in the decades around 500 could not have been achieved without such indigenous collaboration. Paradoxically, though, Clovis made sure of the approval of the emperor in far-off Constantinople: the idea of empire persisted even when, and where, no eastern cavalry would ever appear over the horizon.

There never was any neat coincidence between the Roman Empire and Europe: on the one hand, much of the European continent was beyond the bounds of the empire; on the other, the empire stretched, eastwards and southwards, into large swathes of Asia and Africa. What happened in the centuries between c.400 and c.1500 was that Europe took shape, filled its spaces, acquired an identity of sorts. The result was a world with clear debts to Rome, but just as clearly, very different from it. To weigh up the contrasts and the continuities – and to observe the contrasts emerging as more important than the continuities – the most direct way is to consider religious change over the long run. First, Christianity grew up within the Roman Empire, to become its official religion in the fourth century. An emperor’s act of state could not magic cultural integration into being. Over many centuries, however, Christianisation pervaded the forms and norms of the old empire and spread far beyond: it was not Roman-imperial but medieval missionaries who took Christianity to the lands beyond the Rhine: (using modern terminology) to Scotland in the seventh century, Germany in the eighth, Denmark and Sweden and Norway in the ninth and tenth, Poland, Czechia and Hungary in the tenth and eleventh. Even that picture of a process is too tidy: there is always an exception, in this case Ireland, never part of the Roman Empire but converted in Roman times by multiple individual efforts, a spin-off from contacts established through trading, including slave-trading. Thus Irish missionaries played a part in many of those earlier-medieval enterprises which by c.1000 had brought most of western, northern and central Europe into Christendom.

In c.1000, that Christendom was one. At the same time, it was, for all practical purposes, divided. Divided, first, in the sense that there were, even among those kingdoms and people converted by Latin-using missionaries, multiple local and regional churches with distinct cultic traditions which, given the importance of ritual in religion, mattered a great deal to their practitioners. There were also distinct structures of church government within the various kingdoms, and in these churches-within-kingdoms, churchmen unsurprisingly operated with the support of kings and aristocrats. Although the pope was recognised as the successor to St Peter and custodian of Peter’s relics in Rome, papal authority was precisely of this cultic kind. Many pilgrims journeyed to Rome, yet seldom did earlier-medieval Christians appeal to the pope for judgment. Bishops and archbishops in their own church councils ran ecclesiastical government on provincial lines.

Christendom was divided, too, on grander lines. Rome was only one of five patriarchal sees: the other four, reflecting the eastern Mediterranean origins of Christianity itself, were located in the eastern Roman Empire, in Constantinople – that was naturally the most important, being the imperial capital – and in Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. By c.1000, Constantinople (for reasons to be outlined presently) was left as the only politically significant eastern player: its patriarch confronted the pope in Rome as one ecclesiastical leader to another. ‘Confronted’, however, only in a figurative sense: for one thing, there was seldom any issue that divided them, for another, patriarch and pope never actually met, since in the three centuries before 1000, there was relatively little ecclesiastical coming and going between western and eastern Christian worlds, and occasional embassies could take care of such contacts as there were. As within the West, cultic differences had insensibly come into being, and grown, between East and West. The eastern emperors had never given up their universal claims. Though they grudgingly acknowledged western emperors from Charlemagne on, they never recognised them as Roman: instead the Greek-speaker with his capital in Constantinople was the sole basileus Romaion, emperor of the Romans. (‘Byzantium’, ‘the Byzantine Empire’, are modern historians’ terms which no basileus would ever have used.) Charlemagne’s grandsons, in the ninth century, were powerful enough as kings to have political ambitions in central Europe. Here they inevitably competed (‘clashed’ would overstate the case) with Constantinople’s ambitions to extend its cultural and diplomatic influence. Missionaries, from the barbarian successor-states to the Frankish empire on the one hand, Byzantium on the other, vied to convert Bulgars, Moravians, and Russians. Geography had much to do with outcomes. By c.1000, the dividing-lines of European Christendom between East and West had been fixed where they remain today: with Poland, Czechia and Hungary, and, further south, Croatia, in the Latin Church, Bulgaria, Russia, and Serbia in the Greek one. Yet c.1000, a German bishop, hearing of Greek clergy’s conversion of the Russian prince, rejoiced that he was now with ‘us’, meaning Christians. In both East and West, there was still a sense of Christendom as one.

That sense, at least on the part of churchmen, was fostered from the seventh century onwards by the rise of Islam. Within four generations of Muḥammad’s death in 632, Muslim armies had conquered much of what had been the Asiatic and African provinces of the Roman Empire – Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa including what are now Libya, Algeria and Morocco – and finally, in 711–14 virtually the whole of the Iberian peninsula. Constantinople lost all its eastern provinces except Anatolia which nevertheless suffered repeated raids. In the Mediterranean itself, Arab fleets conquered Cyprus and later Crete (825) and Sicily (827). Churchmen in both East and West, when they mentioned these disasters, attributed them to divine punishment for Christians’ sins and called for repentance. Yet for the most part, regarding those they called ‘Saracens’ or ‘Hagarenes’, churchmen said little and, as far as religion went, understood less. Within regions under Muslim rule, Christians suffered no persecution unless they courted martyrdom. Church leaders in Córdoba and Carthage, Damascus and Jerusalem advocated a policy of peaceful coexistence. Christian potentates, especially in the West, did not differentiate on grounds of religion between those rulers with whom they entertained diplomatic contacts: Charlemagne received envoys from ‘the kings of the Irish’ and ‘the king of the Persians’, the latter’s being more welcome because their master was far more prestigious and sent far richer gifts. By c.1000, the emirate at Córdoba had declared itself an independent caliphate and its power was at its zenith. The envoy of Otto I of Germany to Córdoba was mightily impressed, in 953, by the caliph’s wealth and military power, and thought his regime might have something to offer by way of a role-model to a German kingdom racked by intra-dynastic disputes and regional rebellion.

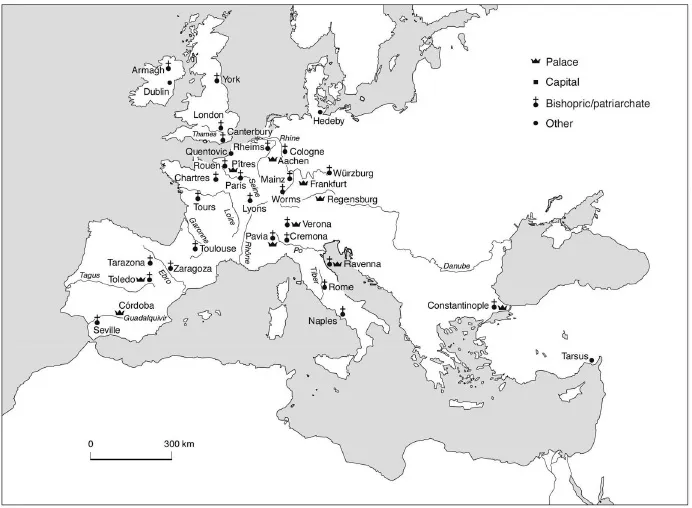

Figure 1.1 Map of early Medieval Europe.

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, this relatively comfortable world of live-and-let-live changed dramatically and permanently, as Latin Christendom went on the march. The motors of change were demographic and economic growth. Western aristocracies and peasantries alike were producing larger numbers of surviving offspring. These could not be contained within the old structures of settlement and landowning. Adjustments that over centuries had been gradual and obscure now tipped into explosive change. New lands were brought into cultivation and new villages and towns proliferated with the encouragement of lords; output increased, as did the volume of exchanges between countryside and towns. By c.1200, significant sectors of the economy were effectively monetised. Aristocratic youths competed for the lands, heiresses, the profits of war. Colonising efforts led and manned by ambitious and aggressive nobles also involved the mobilisation of peasant enterprise. Western Europe began to expand on frontier after frontier: in the British Isles as Anglo-Saxon, then Anglo-Norman, war-lords and settlers moved into the Celtic lands; in Spain as Leonese–Castilian and Aragonese, with plenty of French freebooters in support, took first treasure, then territory, from the now-fragmented states of Muslim al-Andalus; in southern Italy and Sicily, as Norman mercenaries-turned-colonists carved out for themselves a kingdom in the sun; in Palestine with the establishment, mostly by French and Flemish and (again) Norman nobles, of a Latin Christian kingdom and satellite principalities in the wake of the First Crusade (1099), then with the creation by Italian merchants of commercial enclaves in the coastal towns of Syria and Palestine and also in the great ports of Byzantium; and in central and northern Europe, as German nobles and their followers imposed their lordship over Slavs and others in the Baltic lands. It was not all aggression and expropriation: on some of these frontiers, especially in central Europe, there was peaceful settlement on newly cultivated lands and in newly founded towns. But one story of Europe in the central Middle Ages is of militarism, colonialism, and racism. Some of its main aspects are the themes of chapters in Part I.

The Europe that expanded was Latin, not Greek: indeed Latin Europe’s expansion was at the expense of, among others, the Greeks. Relations that, with ups and downs, had been relatively smooth in the earlier Middle Ages now became rough; and a breach over ritual differences and ecclesiastical politics in 1054 that seemed reparable in the twelfth century was made irreparable after the conquest and plundering of Constantinople in 1204 by westerners on the Fourth Crusade. The late medieval West integrated word and image, now in secular books written for lay readerships, in its appropriation of shared antiquity. In the Eastern Mediterranean, crusading, primarily directed against Muslims, always involved Eastern Christian victims as well. In western Europe, Jews were victims of savage pogroms at the time of the First Crusade (1096). A European identity was formed at the expense of minorities: to identify and organise was also to exclude. There was a clear link between crusading and the persecution of the Jews. In Spain, where Muslims, Christians and Jews had co-existed, and even in a few cases co-operated intellectually by the fruitful exchange of their various readings of classical philosophy and cosmological lore, the spirit of live-and-let-live came under increasing pressure. By the mid-thirteenth century, the policing of the frontiers of Latin Christian belief and cultic practice had been assigned to professional inquisitors, and heretics as well as infidels were on the run. While Byzantium retained a sense of its own imperial distinctiveness, some western Europeans, and these included traders as well as missionaries and scholars, were becoming aware of cultures far to the East, beyond the Byzantine empire and beyond Islam. The forms and tempo of external contact varied in different regions. Hungary’s self-identification came in the fourteenth century, by reference to the pagan Cumans. By the later Middle Ages, Europe had become Europe by negation: by asserting what it was not, and by proscribing assorted Others.

One European identity, or perhaps one set of identities, forms much of the substance of the stories in Part I. These stories, articulated in the late twentieth century, are well-suited to the mood of post-colonial times. There are other possible stories, though, and other more positive images of medieval Europe emerge in this book. In terms of recent historians’ writing, the Latin Christian Church stands in the centre of contested territory: persecutor or emancipator, instrument of oppression or enabling agency? Marxist historiography contributed much to the demonising of a feudal Church, aligned with the powers that were, manipulating and exploiting the ignorant. Yet it was Antonio Gramsci who identified Saints Francis and Dominic and their followers the friars as prototypes of organic intellectuals, by which he meant that they identified with and articulated the interests of the poor and unprivileged. The Church itself was both the site and the agent of social change. As a collectivity of believers, it represented demand for cultic and symbolic adaptation to new circumstances. As an institution, it responded to such demand. The Church was the beneficiary of demographic and economic growth: new land, new recruits, and new money made possible new church foundations and new and larger church schools producing trained personnel. The availability of new capital and new cadres made possible institutional consolidation. A centralised ecclesiastical government presupposed widely supported means and ends. The means were supplied by the income from Christendom-wide taxation to which the crusades gave the first big spur. The ends were provided by the needs of increasing numbers of churches (with a small ‘c’), and also of lay individuals and communities, for authoritative intervention in their disputes over power and resources. In the earlier Middle Ages, such disputes had generally been resolved locally, by consensus or by violence. In the central Middle Ages, a larger and more differentiated world required new agencies of organisation and conciliation. No secular regime could supply these on the scale required. The popes of the central Middle Ages capitalised on a unique set of circumstances, responded to demand, found qualified agents and supporters. Thus was created the first great European government, the high-medieval papacy – perceived by contemporaries (who were anything but naive) not just as the venal instrument of vested interests, but as a utility, and a force for good. This book faithfully represents the complexity of the medieval Church as a distinctively European phenomenon – as the conduit of authority which legitimated the power exercised by Europe’s secular rulers, and as the institution which, while proclaiming the belief that there ...