I

IT WOULD SEEM OBVIOUS that there is no such thing as “the revolutionary personality.” Revolutions are of various kinds, and this alone would seem to demand different sorts of revolutionaries. A saintly Gandhi and a demonic Hitler must both be allowed their place in the spectrum of revolutionary leaders.

There is the possibility that underneath the saintly and the demonic qualities a common personality exists. It is this assumption that animates those who speak as if all revolutionaries were basically alike; for example, oedipal sons out to destroy their fathers in the guise of attacking established political authority. Whatever the grain of truth in this assumption, and its occasional fit with the facts, further reflection points to its grossness as a general theory and its utter simplicity in the face of the multiplicity of actual revolutions, with the resultant emergence of varied sorts of leaders and followers.

Does this mean that any effort to inquire into the personalities of revolutionaries, with the aim of establishing some sort of general theory, is foreordained to failure? In my view, it suggests only that we must proceed with great caution, with due regard for the varied nature of revolutions, and with constant attention to the actual facts.

One such “fact” seems to be the frequent appearance in revolutions and revolutionary leaders of what are loosely called “puritan” or “ascetic” qualities. These have been noticed by many observers. For example, an eminent student of revolutionary behavior, Eric Hobsbawm, remarks:

There is, I am bound to note with a little regret, a persistent affinity between revolution and puritanism. I can think of no well-established organized revolutionary movement or regime which has not developed marked puritanical tendencies…. The libertarian, or more exactly anti-nomian, component of revolutionary movements, though sometimes strong or even dominant at the actual moment of liberation, has never been able to resist the puritan. The Robespierres always win out over the Dantons…. Why this is so is an important and obscure question, which cannot be answered here. Whether it is necessarily so is an even more important question.1

Why do Robespierres win out over Dantons? Does André Malraux hint dramatically at the answer when he reminds us of the dialogue between Robespierre and Danton in the corridors of the Assembly shortly after the latter’s second marriage? “You’re conspiring, Danton,” Robespierre accuses his “friend.” “Don’t be an imbecile,” Danton replies, “you can’t conspire and fuck at the same time.”2 If Robespierres always triumph over Dantons, do Robespierres also inevitably appear in all revolutions? A moment’s reflection on the American Revolution will dispel this supposition. Yet we are left with the conviction that, as Hobsbawm states, “puritanical tendencies” loom large in revolutions, or at least in our perception of them.3

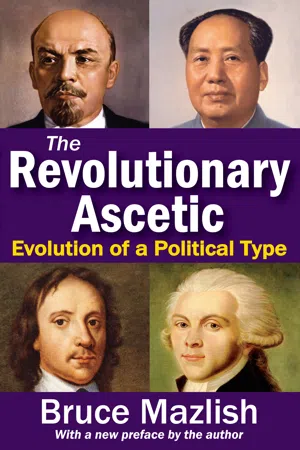

Having asserted that there is no such thing as a “revolutionary personality,” we now maintain, however, that there is a cluster of traits, which Hobsbawm calls “puritanical” and sees as epitomized by Robespierre, which bears investigation as possibly appearing with unusual frequency in the personality of revolutionaries. Not all revolutionaries will have these traits—one thinks immediately of a Danton or a sensual Sukarno—and not all who have them will be revolutionaries—a de Gaulle or a Nixon (who sought to model himself after the French leader) appear quite “puritanical” but are hardly revolutionaries. Thus it is those who are revolutionaries and exhibit a high quota of “puritanical tendencies” who interest us here. We shall examine them under the concept of what we shall call “revolutionary ascetics,” and seek to understand what role and function, consciously and unconsciously, politically and psychologically, both for leader and led, their tendencies fulfill.4

II

OUR REVOLUTIONARY ASCETIC is an ideal type to which any existing individual will only partially correspond. The ideal, however, prods us to keep a sharp eye out for the traits exhibited by a given revolutionary leader, as well as by particular revolutions. The concept of revolutionary ascetic is made up of three parts. First, the ascetic traits must be placed in the service of revolution. Since, in my view (to be spelled out a bit more shortly), revolution is itself a relatively recent social invention or means of social transformation, the problem is to trace how it becomes linked to asceticism. In any case, the term “revolutionary” is meant to set off our subject from other kinds of practitioners of asceticism, especially traditional religious ones.

The “ascetic” part of our “revolutionary ascetic” is itself made up of two components. One is the traditional cluster of traits associated with the word “ascetic”: self-denial, self-discipline, no “wine, women, and song,” and so on, all in an effort to reach some high spiritual state. It has been the genius of Max Weber to take such traditional religious asceticism in the West and show how, in the guise of worldly asceticism closely connected with Calvinism, it was enlisted in the service of modem capitalist, economic activity.5 Following Weber, we shall try to show how such ascetic traits were also later put under the banner of revolutionary activity.

In addition to the traditional ascetic traits, we incorporate in our use of the term “ascetic” another element, derived from Sigmund Freud. In his essay “Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego” (1921)6 Freud analyzed leadership in terms of the leader who had “few libidinal ties.” We shall seek to explain precisely what this means psychoanalytically, and grapple with its consequences in detail in Chapter 3. Here we can say in general terms that the leader with “few libidinal ties” points at the character traits in an individual that may permit him to deny the normal bonds of friendship, feeling, and affection, and to eliminate all human consideration in the name of devotion to the revolution. A Robespierre can send his friends, Desmoulins and Danton, to the guillotine without any compunction. A Lenin refuses to listen to Beethoven’s Sonata Appassionata because it may weaken his revolutionary resolve. As Stendhal reminds us in The Charterhouse of Parma, “revolutions are not made with kid gloves”; in the novel, the failure out of squeamishness of some Spanish revolutionaries to eliminate some of their opponents meant the failure of their revolution itself.

For Freud’s phrase, “few libidinal ties,” I am using the term “displaced libido,” meaning that the individual has few libidinal, or loving, ties to individuals, but has displaced them onto an abstraction, in this case the revolution.7 It is the combination in a true revolutionary of displaced libido with traditional ascetic traits that I have in mind when I speak of the “revolutionary ascetic.”

Thus I am seeking to combine inspirations from sociologist Max Weber and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud in investigating the phenomenon of “revolutionary asceticism.” Weber concentrated on asceticism as traditionally defined, and then traced its historical development in the West; he paid no attention to the problem of libidinal ties. Freud gave surprisingly little attention to the analysis of asceticism, but he did inquire in depth into the leader with few libidinal ties, and offered a kind of “scientific myth” as to how such leaders were fundamental to the establishment of human societies.8 It seems to me profitable to synthesize the insights and theories of these two great seers into one concept of the “ascetic,” and then to link it with the phenomena of revolution: hence, “revolutionary ascetics.”

III

A BRIEF WORD must now be said about the concept of “revolution” itself. On this subject a vast literature has grown up, and it would subvert our purposes if we became too engrossed in the topic by itself. However, for an understanding of our view of revolutionary ascetics we need to establish a few guidelines. First, a definition is in order. While few students of the subject agree precisely on the definition of revolution, samples of some standard ones will be useful. For Sigmund Neumann, revolution is “a sweeping fundamental change in political organization, social structure, economic property control and the predominant myth of a social order, thus indicating a major break in the continuity of development.”9 For Chalmers Johnson, we may paraphrase it as:

Violence directed toward one or more of the following goals: a change of government (personnel and leadership), of regime (form of government and distribution of political power), or of society (social structure, system of property control and class domination, dominant values, and the like).10

If we accept some such definition of revolution, we are then faced with the task of discriminating among different types of revolution. Historians, political scientists, and sociologists have all tried their hand at establishing typologies of revolution. At the very least one is aware of so-called colonial revolutions, nationalist revolutions, modernizing revolutions, and so forth. More precise efforts at typology are embodied in, for example, James Rosenau’s division of revolution into three major types of “internal war:” that is revolution: what he calls “personnel wars,” “authority wars,” and “structural wars.” Chalmers Johnson suggests a sixfold typology: jacquerie, millenarian rebellion, anarchistic rebellion, Jacobin Communist revolution, conspiratorial coup d’état, and militarized mass insurrection.11

Such typologies of revolution, and the definitions given earlier, still leave us with numerous problems. Do any of these ideal types help us decide whether the Nazis led a revolution? What is the difference between a “colonial revolution” in the name of modernization under the presence of Western imperialism and one animated by a root-and-branch opposition to all things Western? Is the Chinese Revolution an example of the latter? Was the Cuban Revolution originally intended by Castro and his followers as a “structural war,” or did it become so accidentally? Such questions suggest the complications of understanding revolution and, by extension, the nature of leadership in such differing types of revolution.

There is also the historical dimension to be considered. Is revolution the same thing in the seventeenth century as in the twentieth century? Is it the same in a period or society dominated by religious modes of thought as against one in which modern scientific-technological modes of thought dominate? Does the existence of a prior revolution, such as the French, mold drastically the perceptions about revolution of those who come afterward and try to make their “own” revolution? Such questions, mainly rhetorical, again suggest the diversity of conditions surrounding the emergence of revolutionary personalities, including our revolutionary ascetic.

From this welter of problems surrounding the subject of revolution, for our purposes let us stress a few salient assertions. The first is that revolution is essentially a modern phenomenon, dating in its earliest form from about the seventeenth century. At that time the word “revolution” itself, though used sporadically earlier in Greek and late medieval or Renaissance writings, was taken from the astronomical sphere and applied to the political as well. In both spheres it meant a cyclical movement (as in Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies). Such a cyclical movement, or revolution, ended by a return to its original position, i.e., a restoration. Thus political revolution meant an irresistible force, something in the stars mysteriously affecting man’s destiny on earth, which caused political affairs to rotate through a cycle. In this usage it echoed the earlier Greek notion, as propounded, for example, in Plato, that states went through a cycle from despotism to democracy and back again.

It was the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which, as Karl Griewank informs us, “permanently introduced the word revolution into historical writing and political theory.”12 The earlier events of 1640–1660 had been introduced into historiography by Clarendon, its first historian, as “The Great Rebellion” (it was not until the early nineteenth century that Guizot made it known under the label “The English Revolution,” and after the middle of the century that S. R. Gardiner called it “The Puritan Revolution”!). The Glorious Revolution, “revolutionary” as it was, was seen as “restoring” England to its rightful position and liberties before a tyrannical king sought to usurp the situation.

In spite of such a “conservative” usage, however, there had been a violent political movement in 1640–1660 which men gradually began to recognize as the first modern, large-scale social transformation of the genus revolution. So, too, 1688–1689 was recognized as a genuine mutation, a transition, as Griewank puts it, “to a new dynasty upon new conditions which, with whatever foundation in law, had been laid down by Parliament.”13 What is more, in the seventeenth century, political change—revolution—was increasingly coupled, even if only half-consciously, with the emergent idea of progress. Such a coupling broke the tie of revolution to cyclical movement, and thus to restoration, and forged a new connection to linear development. As a result, by the end of the seventeenth century a new concept of social transformation, revolution linked to progressive forces, had emerged. The fact that this sort of revolution was no mere accident was confirmed in 1789 and thereafter by the institutionalization of revolution as a means of social change, as evinced both by events (the revolutions of 1830, 1848, and so on) and by men’s thinking on politics. It is on the basis of the development sketched above that we have asserted that revolution is a modern, Western development, effectively dating from about the mid-seventeenth century.

The new coupling between “revolution” and linear progress took a while to become obvious. Thus our second point is that modern revolution—and henceforth we mean only this usage—has become an increasingly conscious means of social transformation. Only gropingly present in the English Revolution of 1640–1660 (the so-called Puritan Revolution), in terms of Levellers and Diggers, this fact emerges more convincingly in the French Revolution, and is enshrined in the notion of “ideology” which takes its rise from that momentous event. Henceforth, men consciously plan revolutionary overturns of society.

Such men, and this is our third point, often make revolution their profession. A Blanqui or a Buonarroti, prefiguring a Lenin or a Mao, have no career other than that of professional revolutionary. It is their sole “calling.” And at this point we can see how a connection can be made to Max Weber’s theory of ascetic traits, hitherto religiously oriented, then utilized for economic activity, and now placed in the service of revolutionary activity.

This notion leads to our fourth point, which concerns the question of “modernization.” While we cannot say much about this large topic here, we need to signal its importance in relation to revolutions. Modernization is a complex notion, usually taken to involve such factors as industrialization, increasing rationality, secularization, and urbanization. Whatever the precise nature of modernization and of the earlier modern revolutions (i.e., through the French Revolution) in this regard, the revolutions of the twentieth century have tended to be either “modernizing” revolutions, or else revolutions involved in some way with problems arising from the phenomenon of modernization. In short, as we come to more “modern” revolutions, meaning those of the twentieth century, we must assume that they are centrally concerned with “modernization”—that is, at the very least with coming to terms with the problems involved in existing in a world society characterized by widespread modern technology and science, and with the cultural attitudes that cohere to their use.

Our last point about revolution per se, preliminary to our inquiry into revolutionary ascetics, takes up again the point made earlier about our having to view revolution in an historical dimension. Now we can see that revolution has undergone, and is undergoing, an historical development. This fact has generally been neglected by historians, sociologists, and political scientists, who have tended to offer static typologies in place of dynamic theories. True, they have sought to understand the internal dynamics of revolution as well as its nature—one thinks, for example, of Crane Brinton’s Anatomy of Revolution, with its phases of revolutionary development—but this is not the same thing as depicting and analyzing the dynamics of revolution in the sense of changes in the phenom...