![]()

1

STILLNESS

There’s a commonly observed “Zen” content to stillness. This is a stillness gone into itself – a meditative mode. However, there are other ways of being or becoming still. Note these three states:

A Stillness as arrest

B Stillness as a state

C Breaking out of stillness

The Zen of Stillness concerns B – a composed state which deepens when one adopts a position which is easy to hold for a long time. The Zen endures, perhaps from the beginning to the end of the piece. Perhaps it begins before the beginning and ends after the audience have gone.

Other notions of stillness emerge. Arrested Stillness for instance, when the performer suddenly stops performing, to become engaged in listening or watching. Here the stillness is that of the witness. On stage, in conventional drama, it’s common for one person to move or talk while others watch or listen in a position of stasis, their actions arrested or interrupted.

Then there is stillness as Death or Collapse. This may often occur after the expenditure of effort. In a dull workshop, this is the commonest, most obvious sort of immobility. One simply lies down on the floor. Limp performers can be dragged into other positions: imagine how the prince may have diverted himself before he actually kissed the Sleeping Beauty. Sleep simulates death, and stillness in a relaxed position performed with the eyes closed will always evoke the dream or the swoon. But there is also the terrifying stillness of Rigidity, which may be the tense, static convulsion of madness or the stiff immobility of death (as in Rigor Mortis).

Death stillness is a non-Zen version of B. But death may suggest or entail rebirth, so another crucial aspect of stillness is C: breaking out of the contained egg of Zen composure, or recovering from or lifting up out of the stillness of death or exhaustion.

Lacan talks about the significance of edges – how sex is not so much the urge to get inside, or the urge to have something within one, so much as the desire to oscillate across the threshold established between inside and outside. Thus the parts which are the landmarks to our entrances are desirable – lips, anus, labia, slit at the tip of the penis, eyelid and ear – but not the liver, not the lungs.

Zen stillness is a continuous drawing-in to the interior, while the stillness of arrest or a stillness which is broken out of are both conditions which lie across the threshold of stillness. Breaking out of Stillness implies rebirth.

Note also the difference between “stillness” and “stuckness”. For stuckness occurs when arrest is forced or break-out is restrained. Here stillness is imposed on the performer – for example, by ropes or by handcuffs, or by the physical force of other performers. We might call this Stillness by Restraint. Such a state of stillness is suffered, as a bird suffers stillness when mesmerized by a snake. This is the stillness of panic, a form of rigidity – the choice of fight or flight stressfully suspended; a state in which one can neither hear nor see, or rather in which one is dazzled or blinded by what one sees, deafened or shocked by what one hears. It’s a state akin to hypnosis – a seeing in a frozen state, where some inner vision may be prompted by an outsider or by an outside force.

Physical rigidity, or rigour, in performance may read as a catatonic condition; the subject often hiding the hands under the armpits or sitting upon them (poses Breughel uses to depict madness). Here a form of auto-restraint is being practised – the sane part attempting to arrest the unpredictable (and inconsistent) actions of the demented part. Illustrations of patients in lunatic asylums (in Sander Gilman’s Seeing the Insane) show sufferers from catatonia tying their bodies into knots, or arching to the limit, supported only by head and toes – still perhaps, but very tense indeed in their immobility. Here we have the stillness of the spasm, where one muscle is pitted against another as in the performance exercise (and muscle pumping process) referred to as Dynamic Tension. This stillness may even start to vibrate (a patina of repetition), which leads to a shuddering, clenching act, probably evoking frustration or rage.

When I was very young, I saw a hypnotist at a fair in France put someone into a rigid, unblinking pose, supposedly a trance. When his arms were lifted away from his sides and released they would slap down tautly against his sides again. The hypnotist was able to write on his subject’s eyeballs with a pencil.

The History of Stillness

Performance art emerged out of the “happenings” of the sixties. Stillness was manifest as a key factor in such early experiments since many of these events were devised by visual artists in New York who took the static, two-dimensional image as their starting point. A happening might incorporate a statuesque pose, such as Carolee Schneemann’s Olympia pose in Robert Morris’s Site, first performed in 1965. In this piece, the stillness of the pose from Manet’s painting provided a contrast to the other artist’s active manipulation of the white panels surrounding it.

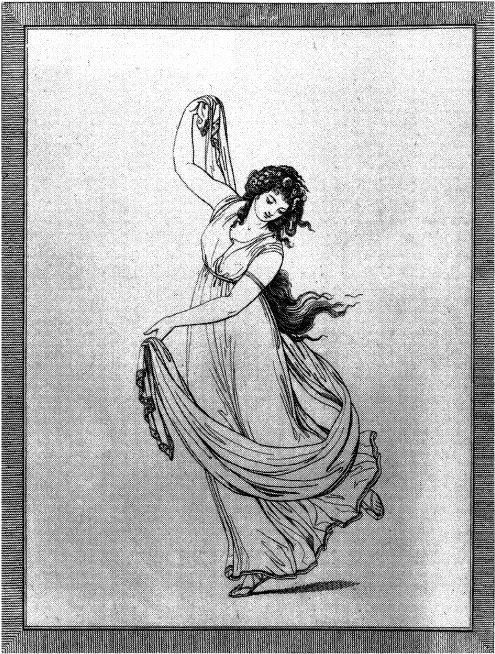

The notion of becoming a painting, of being a painting incarnate, inspired many of the tableaux of previous centuries. Such living images should be part of any history of performance art. In The Paul Mellon Seminars 1996-7 – organised by Chloe Chard and Helen Langdon – the significance of Emma Hamilton was emphasised in the development of such posed performances – which were popular in the late eighteenth century.

Emma Hamilton in The Muse of the Dance – one of her ‘attitudes’ – etching by Rehberg, courtesy of the British Museum.

Performance art’s affinity with visual art rather than theatre can be traced back to the tradition of life-modelling – in which stillness has always been recognised as a skill. Chloe Chard informs us that at the end of the eighteenth century Paolina Borghese, Napoleon’s sister, posed in the nude for Canova’s sculpture of Venus – and thereafter the Prince, her husband, kept the statue under lock and key! It is Emma Hamilton, however, who turned the art of the model into an art in its own right in the 1790s. In her tableaux, immobility was of short duration, and her attitudes were remarkable for the transitions of mood she was capable of achieving. Chard quotes from the reminiscences of the painter Elisabeth Vigeé-Lebrun:

“Nothing was more curious than the faculty that Lady Hamilton had acquired of suddenly imparting to all her features the expression of sorrow or joy, and of posing in a wonderful manner in order to represent different characters. Her eye alight with animation, her hair strewn about her, she displayed to you a delicious bacchante, then all at once her face expressed sadness, and you saw an admirable repentant Magdalene.

(Spectral Souvenirs, page 4)

Vigeé-Lebrun describes these attitudes as ‘ce talent d’un nouveau genre’. The new genre was performance art. Emma Hamilton used what might be called ‘bursts of stillness’. Deducing an understanding of her attitudes from the descriptions of contemporary writers, Chard notes that;

“Emma dramatically draws attention to the disjunction between the immobility, permanence and aloofness associated with the art of sculpture and the animation of a living human being.”

(Spectral Souvenirs, page 18)

Robert Wilson’s performance tableaux were celebrated for their employment of stillness and slowness in the seventies. In his fine book on Wilson’s theatre, Conversations with Sheryl Sutton, Janos Pilinsky talks of le drame immobile (see Appendix 2). In such drama the suspension of action has more potency than the conventional unfolding of a plot. The issues raised by this immobility are expanded upon in the book. And we will discuss these issues and Wilson’s tableaux in more detail when we come to consider repetition and slowness.

Gilbert and George also developed motionlessness in Underneath the Arches, their seminal “singing sculpture”, first shown in 1969, and shown again two decades later – in 1991 at the Sonnabend Gallery – thus confirming the enduring ‘sculptural’ status of the piece. In it, the rendition of commonplace formal poses prompted by an exchange of glove and stick, poses appropriate to the formality of the suits worn by the two performers, was punctuated by the need for one of them to descend from the table upon which these poses were displayed in order to turn over the sound-cassette in the small recorder placed in front of the table. Stick and glove were exchanged and new poses adopted only when the tape was turned, so the length of the tape dictated the length of the pose. There was a certain ‘uncanniness’ about their brand of stillness. Freud considered automata uncanny, and noticed an ambiguity about the German word unheimlich or ‘unhomely’, which the standard edition of his works translates as ‘uncanny’, observing that homeliness itself can also exhibit uneasy, eerie qualities – in the same way as we can talk about a witch’s fetish creature as her ‘familiar’. About such living statuary there is both familiarity and unfamiliarity. What is familiar is that we are clearly observing living humans in precisely everyday poses: what is unfamiliar is their stillness. And it is the tension between these contradictory qualities which produces the uncanny effect. We shall see that repetition seeks to deny the passage of time, and that inconsistency seeks to establish its passage by creating its markers. Stillness may suggest indifference to time – as a memorial may seem indifferent to the changes of the weather. In his fine essay on “The Uncanny”, which accompanied the exhibition he curated for Sonsbeek 93 in the Gemeentemuseum Arnhem, Mike Kelly points out that there is a memorial quality about statues: they stand on tombs, represent the dead. When the dead object proves ‘undead’ we experience goose-bumps. Consider the voice of the statue of the murdered commendatore in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The utterly lifelike statuary created by the neo-classical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen constitutes his mausoleum, for he is buried in his own museum in Copenhagen.

Tilda Swinton remains still for longer than the duration of an audio-cassette, sleeping through the day in a glass cabinet. The eccentric William Beckford (1760–1844) maintained that sleeping sculptures were more convincing – sleep supplied a reason for their immobility. Tanja Ostojić stands motionless for hours within a square of marble dust. She’s completely shaven, and covered in marble dust herself. With life-like sculpture, we doubt whether the material is really inanimate. With living sculpture we doubt whether the being is really alive. There is, after all, a congealing quality about stillness. We speak of a stilled position as a freeze, and indeed there is an aspect to stillness which suggests coldness – not only the coldness of the lake turning to ice but also the coldness of statues, the coldness of stone. Heat speeds up molecules; while stillness suggests their inertia.

Mention should also be made of a piece by Chris Burden, from California, in which Burden remained in the middle section of a three tier locker for several days. The locker above contained sustenance. The locker below was for excretion. Nothing however was seen but the locker with its three closed compartments. The sounds of bodily functions must have occasionally been heard, but otherwise the piece appears to have been entirely still. One could only contemplate the lockers, knowing that someone was inside.

There is more therefore to stillness than “Zen” depth and physical or psychotic entrapment – more to it than arrest and break-out. The above examples demonstrate the range of this primary action: stillness as a sleep or as a trance, as a painting in corporeal form, as a suspension of the theatrical convention of dialogue and plot development, as indicative of coldness, as an emblem of the enduring quality of sculpture or of the uncanniness of automata – especially after the clockwork movement has ceased or when it suddenly jolts into action – or we can see in stillness a manifestation of sheer physical endurance.

Stillness as a Ground:

It is said that we live in a time/space continuum. In performance art we may consider this a stillness/emptiness continuum. Consider stillness as empty time, into which a performance is to be poured. In the same way, a painter commences with a blank canvas and a composer with a period of silence. These are the grounds upon which their activity occurs. Stretches of blank canvas may remain when the painting is done; just as silence continuously punctuates a musical composition. In a similar manner, the performance emerges out of stillness, stretches of stillness may occur within it, and stillness will punctuate its actions. Before a piece is conceived, a performer starts with an empty space and a durational quantity of stillness within which actions are to occur. Thus stillness may be considered as the ground which persists underneath the other two primaries of action: repetition and inconsistency (see Figure 1(a)).

During the course of this enquiry we will need to examine each of these primaries in psychoanalytic terms. But let us first tackle an issue raised at this preliminary stage. Does the performer choose to develop the piece in an unfixed durational/spacial amount of still/emptiness by simply assembling more and more actions, or does the performer set a limit to the time and a limit to the space and insert actions into that defined area?

In general, painters usually insert their painting into a canvas of an already decided size, though of course there are plenty of exceptions to this protocol. Sculptors often a...