This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The contributors to this volume were born in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong; they have been immigrants, foreign students, settlers, permanent residents, citizens, and-above all-"travelers." They are both geographic inhabitants of various overseas diaspora Chinese communities as well as figurative inhabitants of imagined heterogeneous and hybrid communities. Their migratory histories are here presented as an interdisciplinary collection of texts in distinctive voices: law professor, journalist, historian, poet, choreographer, film scholar, tai-chi expert, translator, writer, literary scholar.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Chinese Women Traversing Diaspora by Sharon K. Hom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Too Many Things Forgotten …

Too many things already forgotten

But we still want to do this and that, go here and there

To seek limelight or play the coquette

We forget things we did, right or wrong

We forget people we knew, loved or hated

We forget too our experience in the womb before birth

Forget the fear that came with first menstruation

We are too anxious to become strangers to ourselves

As though the farther we fare from the starting point, the better

We forget too many things

Forget friends’ names and the meaning of many words

Forget that some are in jail for our sake

Forget pretty clothes we wore in childhood

Forget the taste of others spitting in one’s face

Just as though we live only to forget

Just as though we only belong to things forgotten

Everything that has been denied

Our future will also be erased

Our diaries and letters will be sent to ragman’s place

Perhaps, in the fire, we will remember ourselves

Remember some extraordinary sunrises and sunsets

Certain indications are at last connected to others

Remember how our soul was caressed and then devastated

Finally, realizing the significance of all these

The bits and drops that were forgotten

Should tell us how not to waste a life

—If possible

—Tokyo, January 1989

Moving into Stillness

Beginning Journeys

When I was about four or five years old, a great typhoon swept through Hong Kong. My family lived in the New Territories, above the factory that my father managed. Across from us was a field of lotus, and beyond that were hills. Sometimes we would see people in boats picking lotus seeds among the blooming flowers. Other times we would see people trekking up the hills. As children, we would wonder excitedly whether they were smugglers. Most of the time, there weren’t too many people in sight. On the other side of the road across from where we lived was a little store that carried knickknacks and candies. It was really only a wooden shack with an open front. The family who owned the store had several children, ranging from very young to teenagers, and they all lived in the back.

I don’t remember much about what happened during the typhoon. It was the calmness after the storm that I remember. There was a great deal of flooding, and the lotus field was submerged under muddy water. The water covered the road, so you could no longer see where the road ended and where the lotus pond began. Some vegetation that was used to feed pigs floated on the surface, slowly drifting away. The flood was so high that the little store was half under murky water. There was only the music from the small radio playing in the store. One of the older children in water up to her waist was cleaning the store. She was using a broom to sweep the water surface. As she swept the floating vegetation, leaves, and paper junk out toward the street, other things continued to float into the store to take their place. However, she did not seem to think this activity futile nor did she seem to mind. She was in no hurry either, but continued this unusual chore. As a child, I remembered this scene in relation to the peacefulness after the storm. As I grew older, it came to mean many other things.

I was born in Shanghai the year after Japan surrendered in World War II. When my mother was pregnant with me, there was finally peace and she felt peaceful. She always tells me that is why I was a happy child. When I was little, I danced all the time, at home, in school, up and down the movie theater aisles while people were waiting for the movie to begin. My family gave me a lot of encouragement. I felt everyone loved to see me dance.

I took dance classes when I was growing up in Hong Kong. Mrs. Cook, a wonderful ballet teacher, taught in a bright, airy church with a high steeple and tall, narrow windows that opened to the trees and birds outside, and to the sky. I also took some Chinese folk dance classes, but they were repetitive, not very interesting, and I didn’t study very long. When I was older, I studied Peking opera with Chi Tsai-fung, a contemporary of Mei Lang-fang. He taught me the composure and beauty of simply standing still. I learned a great deal of the aesthetics of this classical art form, which could not be learned from books or other visual materials. But Chi Tsai-fung passed away before I could study further. I graduated high school from Maryknoll Convent School in Hong Kong. For my high school certificate examination, I received a distinction for music because I had had the best piano teacher for eight years, Betty Drown, a remarkable woman whom we called Auntie Betty. She never sat down and played for her students, yet she trained many of the best musicians in Hong Kong. What she taught me in music theory and structure played an important part in my life and my career in dance.

In the late 1960s, I followed in the footsteps of my older brothers and went to the United States. I attended the University of California at Berkeley, where I studied sociology, and I found the study of society and its people fascinating. It especially touched a chord in my heart when a surge of Chinese people immigrating to the United States in the late 1960s posed a myriad of issues, in terms of assimilation, acculturation, or simply adaptation to a new life-style. I felt particularly for the children of these immigrants, most of them struggling to learn the unfamiliar language and to cope in school as well as at home. I initiated an English tutorial program for children at the Chinatown Y in San Francisco. The plight of immigrants, their uprootedness, their hidden sense of uncertainty and great fear made a deep impression on me.

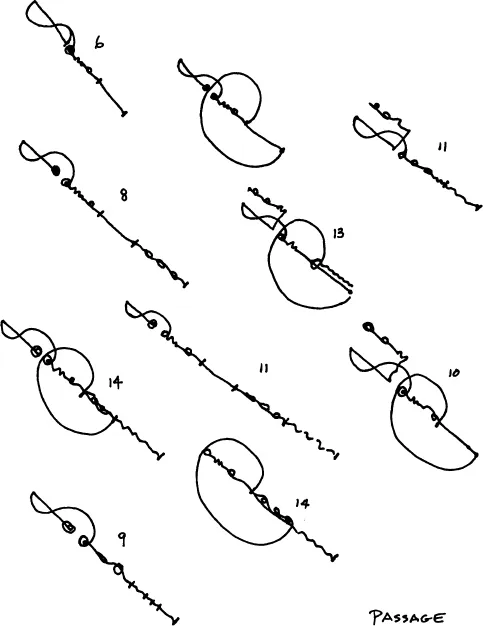

In the late 1970s, I choreographed Passage, one of my earlier major group dances, which explored this dilemma of immigration, leaving one’s familiar home to live in an alien land, moving from one culture to another, and was about transformation. I used improvisational Korean shamanistic music, which was also a practice toward transformation. I have always been fascinated and moved by the process of initiation, the slow and forced passage of many dimensions transforming a people, a culture, into a somewhat different entity. This entity, as it evolves, must constantly renew to sustain itself. While doing so, it undergoes extreme stress and labor. The outcome, however, while open-ended and sometimes painful, is often very different and beautiful.

I wanted to use egg masks (white masks in egg shape with no openings for eyes or nose), but I couldn’t because of the technical problem of dancing while wearing them. This was an extremely demanding piece for the dancers. The primary concern was their focus. Each had to develop a keen sense of focus towards the direction she was traveling onstage. Kwok Yee Tai, then CETA artist, designed the costumes. The dancers were in colorful, elaborate, traditional-like robes, made from sheer, shiny fabric, and patched to look like the paper dolls used for burning in rituals for the dead. As the piece developed, layers of this costume were shed until finally the dancers were in neutral solid colors of beige, pale blue and gray cotton shirts and pants. Another visual aspect of this piece was the long strips of black cloth tied to each dancer’s crown. These strips hung behind down to the knees and would twirl as the dancers moved, a striking accent to the costumes.

In the early 1970s, I studied dance education at Teachers College in New York and, with Teddy Yoshikami and Sin Cha Hong, organized the Asian American Dance Theatre. Aside from choreographing dance pieces, I became involved in the complexity of arts funding and the laborious task of administrating a small dance company with the obscure goal to create “Asian American” dance. For the next fifteen years, I was very busy. Not only was I creating dances and putting on productions, but I was also giving dance classes, coordinating programs, writing proposals, balancing budgets, advocating for contemporary and traditional Asian dance, and complaining and protesting about the lack of support for ethnic and minority community arts. I received many critical reviews of my work, including a choreography fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts.

During these fifteen years, against the backdrop of the changing landscape of Asian America and the nation, the Asian American Dance Theatre evolved constantly in response to its changing environment. When the dance company first began in the early 1970s, it was to demonstrate that Asian people in America could choreograph and dance contemporary works just like other artists. I would meet people who would first be surprised then commend me for my English-language ability. When they heard that I danced, they would assume that I danced only traditional Chinese dance. When I formed the dance company, I choreographed Asian American dance in response to questions about where I came from, and why I could speak English. After a few years, in response to the limited of knowledge about Asian people and culture on the part of mainstream American society, the company began to include traditional dances in its repertoire. Even most Asian people had limited exposure to Asian dance: Chinese dance was often equated with the ribbon dance, and Japanese dancers were expected to look like dolls. I realized the purpose of the company should be to educate the public about the diversity, intricacies, artistry, and beauty of Asian dance.

Although Asians have been in America for many generations, and continue to be a growing population, the history of Asians in America and their activities are not in the mainstream consciousness of this nation. This lack of appreciation of our presence drives us to seek affirmation, and as cultural workers, to create more arts programming. It is as if there were an insatiable thirst for acknowledgment for our arts, and as many cultural programs as there were, could provide only a drop of cultural nourishment to those immigrants, whether they were first, second, or third generation. As community culture workers, we found ourselves reinventing the wheel again and again. In promoting Asian American culture, the dance company expanded to include a community school, touring activities, education programs, as well as the annual New York season at major concert halls. The organization further evolved to include visual arts and folk arts programs as well. Soon the Asian American Dance Theatre changed its name to the Asian American Arts Centre to reflect its diverse programs.

I was sometimes criticized though, because we were performing traditional Asian dance under the banner of the Asian American Dance Theatre. Some people in the audience at one of the performances even walked out in protest. They did not consider Asian dance to be Asian American, even if it was created in the United States, danced by United State citizens and residents, and part of community culture. However, when I was choreographing back then, Asian American dance was different from the Asian American dance that I see now. The new generation of choreographers is quite different, most being at least twenty years younger, with different education, upbringing, and exposure. Their languages and the ways that they identify themselves are also different. That’s why when people ask me what Asian American dance is, I have to say I don’t really know. It can be anything you want it to be. Then asking whether it exists is like asking whether you or I exist. The answer is that Asian American dance is as real and diverse as you and I.

Asking what Asian American dance is is like asking about one’s identity. Our identities are labels. What I am interested in, is not my identity but what I am after I rid myself of all my identities. If we want to identify something in relation to something else, the labeling is only a reaction to something else that needs identifying. Yet, to me, we are all on a continuum of the past reaching into the future.

Figure 1: Passage floor pattern

Making Dance

In the old Chinese classics, it is said that, poetry is the voice of intention; songs, the tonal recitation of sounds; and dance, images through movement. In other words, poetry explains the contents of thought, songs (music) express the sound of thought, and dance is the outer appearance of thought. The three are closely connected, often referred to collectively in classical Chinese as yue. The character “yue” has many meanings. Pronounced “yue,” it refers to the genre of music. Pronounced “le,” it means “happiness,” “enjoyment.” Pronounced as “yao” it means “to like,” “to love,” “to prefer.” Dance is inferred in all these meanings.

In the Book of Odes, the oldest Chinese collection of poems and songs, it is said, “As the heart moves, it moves into words. When words are inadequate, arms and legs begin to dance.” This we can see in body language. When I talk and gesture, and I find that my words are not enough to express myself, I then use my arms, hands, fingers. The birth of dance arises from the need to express thoughts and feelings. As human beings of mind and heart, everything we do responds to this dual mind/heart element. Without the mind/heart content, dance becomes empty, as if without a soul.

The duality of mind/heart creates intention. Whether we intend to have a big dinner, whether we choreograph a dance, write a book, or decide on a career, is based upon intention. We may be the only species on earth with awareness of our intention. If we are aware of our intention, we can make conscious choices. When we are focused and confident, and when we persevere, our intention can be powerful. When the Wright brothers built their airplane, their intention was to fly. Similarly, when people dance, their intention plays a big part. Their intention may be to dance to entertain and inspire others, to enjoy or challenge themselves, or to speak to the gods, or they may have multiple intentions. In Beijing for example, elderly women often gather in the park in the early morning to dance. Sometimes they put on colorful costumes, wear makeup, fix their hair, bring music, and do group folk dances. Other people practice t’ai chi chuan or some other form of martial arts, or take morning walks. Recently, one can see Western social dancing in the early evenings on a regular basis. To u...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series Editor's Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Points of No Return

- In America

- [Un]Fracturing Images Positioning Chinese Diaspora in Law and Culture*

- The Jet Lag of a Migratory Bird Border Crossings Toward/from ‘The Land That is Not'

- Self-Reinstating and Coming to “Conscious Aloneness”

- Deep into Småland*

- Multiple Readings and Personal Reconfigurations Against the “Nationalist Grain”*

- [Per]Forming Law Deformations and Transformations

- Coming to Terms with History

- Too Many Things Forgotten …

- Moving into Stillness

- Beijing Two

- Growing Up Colonial and Crossing Borders Tales from a Reporter's Notebook

- Roundtable on the Fourth World Conference on Women and the NGO Forum, 1995

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors