This is a test

- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The apocalyptic clashes of culture between the land-hungry whites and the American Indians, which reached their climax in the latter half of the nineteenth century, were among the most tragic of all wars ever fought. These conflicts pitted one civilization against another, neither able to comprehend or accommodate the other. To the victor went domination of the continent, to the vanquished the destruction of their way of life. This volume describes those who took part in these wars, focusing on the Plains Indians such as the Sioux and the Cheyenne, the Apache peoples of the south-west, and their implacable foe, the US Cavalry.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access To Live and Die in the West by Jason Hook,Martin Pegler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

US CAVALRYMAN

INTRODUCTION

This section is not a history of the Indian Wars, nor of the Army as a whole. Rather, it is an attempt to convey to the reader the reality of campaign service of just one part of the United States Army – that of the US Cavalry.

Over the years, the US Cavalry has been glamorised and fictionalised to a point where few people appreciate where reality stops and fantasy begins; my primary aim has been to show what life was really like for the trooper who boiled in the Arizona sun, or froze in the winter Montana winds.

No single volume can cover every facet of such varied service life in exhaustive detail, so it is hoped that this book will serve as a basis upon which the interested reader can build. There are, I am aware, certain areas which the knowledgeable reader will find lacking – officers’ clothing has been dealt with only in brief and dress uniforms could not be covered due to the limitations of space.

Those who wish to know more about the battles and the Indians will have to consult one of the many books that cover the subject and readers will find a comprehensive bibliography at the back of this part. I have tried to select books that are readily available, or, in one or two cases, of particular historical significance. To the authors of these books, I can only offer my thanks. For those wishing to visit the sites mentioned, there is a list of excellent museums which capture the flavour of the period.

Many of the photographs are of poor quality due to the early nature of the equipment used; however, they are a vital link with the past, and it is hoped the reader will make allowances for occasional lack of detail.

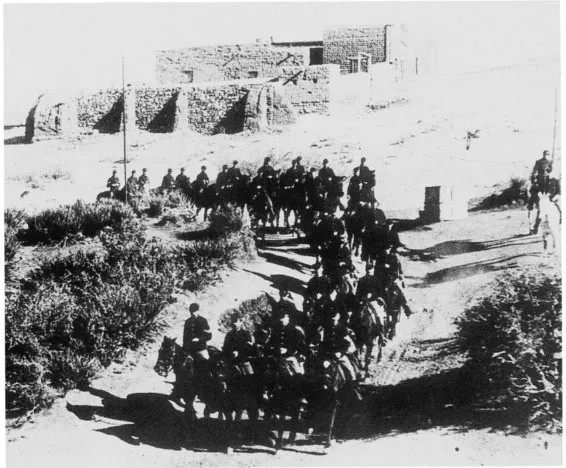

‘A Cavalry troop go on patrol from Fort Bowie, Arizona.’ Their neat appearance and universal 1872 forage caps make one wonder if the true reason for the patrol was for the camera. (National Archives)

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The period 1865–1890 was one of unparalleled change in American frontier history. This span of 25 years witnessed the end of the traditional nomadic lifestyle of the plains Indians, the colonisation of the West by white settlers, and the first experience of the US Army in fighting a form of irregular warfare at which it did not excel, for which its soldiers and commanders were untrained, and its equipment unsuited. The US Army, both infantry and cavalry, were strangers in a strange land. That they acquitted themselves so well in the face of bureaucratic meddling, poor supply and appalling climatic conditions, speaks highly of the tenacity and physical toughness of the volunteers who served in the West.

Until the return of Lewis and Clark from their expedition in 1806, it was generally accepted by settlers that civilisation stopped west of the Missouri river. Beyond, it was believed there was a land both inhospitable and uninhabitable. Lewis and Clark dispelled this myth, and their accounts of vast mountain ranges, forests and prairies populated by incalculable numbers of animals, did much to fuel the wanderlust of restless immigrants. By the mid-1800s the trickle of western-bound settlers had become a steady stream. The Civil War slowed their procession, but the respite was temporary. From 1865, the trickle again became a flood as war-weary men sought a new life, and this new invasion prompted an increasingly violent backlash from the Indians.

Indian conflicts were, of course, nothing new in American history, from the subjugation of the eastern natives by the first settlers, to the forced resettlement of the Five Civilised Tribes – Cherokee, Choctaw, Chicksaw, Creek and Seminole – in the 1830s. The clash of cultures was to a certain extent inevitable, and exacerbated by white greed and duplicity. In the early 19th century, there were approximately 250,000 Plains Indians living a nomadic and semi-nomadic existence in the sparsely populated West and Midwest. The West was home to many tribes, the Dakota being the largest, comprising 13 affiliated tribes generically referred to as the Sioux – these included Hunkpapa, Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Sans Arcs and others who shared common language and customs. Other tribes included Nez Percé, Crow, Cheyenne, Comanche and Arapaho, and in the South-west, Navaho and Apache. Their lifestyle was by no means one of peace and tranquillity. Intertribal wars flared, raids, ambushes, and theft were commonplace occurrences and hunger and disease were constant companions in lean years.

Tribal life centred around the buffalo, and the importance of this animal in native culture is fundamental in understanding much of the subsequent behaviour of the Indians in their dealings with the white man. From the buffalo, and other wild game, came food, clothing, shelter and raw materials for making everything from combs to weapons. Unlimited access to the plains and its wildlife was vital if the Indian was to remain a free man. Most native culture was based around principles of group loyalty and mutual protection. The idea of property or land ownership was to cause much trouble when government officials introduced ownership treaties. This was a concept utterly alien to the Indian mind, as expressed by Tashunka Witko (Crazy Horse), ‘One does not sell the earth upon which the people walk’.

Before and during the Civil War, there had been constant clashes between Plains Indians, settlers and soldiers. In 1862, the Santee Sioux launched a series of attacks in Minnesota. Army action against them served only to further inflame other Dakota tribes, who joined their Santee cousins. By 1865, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Montana and most of Colorado were suffering from regular Indian depredations. New Mexico, Texas and Arizona were also feeling the wrath of the south-western tribes, but the war in the East soaked up all available men and supplies, leaving the western garrisons starved of everything they required to wage war effectively. With the cessation of hostilities in 1865, fresh demands were made upon the President for help in defeating the rising Indian scourge, demands that could no longer be ignored as westward expansion was being actively encouraged by the Government. In practical terms it was impossible to stop, as the lure of goldfields, trapping, timber and limitless land proved irresistible to the war-weary Easterners. As Indian attacks increased on the wagon trains, miners and settlements, so did the need for military protection. To a great extent the Troops in the West were in an impossible situation. They were expected to prevent white encroachment onto reservation land, thus reducing tension with the Indians, whilst at the same time protecting the same whites from physical harm. Over a 25-year period this role changed from peace-keeping to pacification. It became the Army’s duty to put Indians on reservations, and ensure they remained there.

‘Troopers watch for the enemy during the Modoc Wars 1872–3.’ Two wear Civil War ‘bummer’ caps and four-button sack coats. The middle man has his carbine sling and cartridge pouch, the right trooper carries a Sharps carbine. (National Archives)

Major forts and towns of the Indian Wars, 1865–1890.

A Remington Rolling-Block carbine in .45–70 calibre. Not as glamorous as a Sharps or Winchester, but a solid, strong weapon that was well liked by those who used it. (Board of Trustees, The Royal Armouries)

There was money to be made in the West and vested interests on the part of Eastern politicians ensured that protection for the mining and lumber camps, trappers and buffalo hunters, would not be long in coming. Two cultures were on a collision course.

CHRONOLOGY

1865 | The end of the American Civil War. Assassination of President Lincoln. Appointment of Andrew Johnson as President. Start of operations against the Sioux on the Little Big Horn and Powder Rivers. The Tongue river fight (Montana). |

1866 | Gen. W.T. Sherman takes command of the Army in the West. The start of the Snake War. The Fetterman Massacre (Wyoming), The battle of Beechers Island (Colorado), The fight of Crazy Woman Fork (Wyoming). |

1867 | The Wagon Box fight (Montana). The Hayfield fight (Montana). |

1868 | Gen. W.T. Sherman appointed General in Chief. The end of the Snake War. The battle of the Washita (Oklahoma). |

1869 | Appointment of Gen. Ulysses Grant as President. The battle of Summit Springs (Colorado). |

1872 | Start of the Modoc War. The fight at Salt River Canyon (Arizona). |

1873 | The Lava Bed battles (California), The end of the Modoc War. The fight at Massacre Canyon (Nebraska). |

1874 | The start of Red River War The fight at Adobe Walls (Texas). The battles of Tule and Palo Duro Canyons (Texas). |

1875 | Gen. Crook appointed commander of the Army of the Platte. The end of the Red River War. |

1876 | The end of the Little Big Horn and Powder River campaign. The fight of Dull Knife (Wyoming). The battle of the Rosebud (Montana). The battle of Little Big Horn (Montana). Death of Chief Crazy Horse (5 September). |

1877 | Appointment of Rutherford Hayes as President. Start of the Nez Percé and Bannock/Paiute Wars. The battle of Bear Paw Mountain (Montana). The fight at Canyon Creek (Montana). The fight at the Big Hole (Montana). The battle of White Bird Canyon (Idaho). |

1878 | The battle of Willow Springs (Oregon). End of the Nez Percé and Bannock/Paiute Wars. |

1879 | The Ute War. The Thornburg and Meeker massacres (Colorado). |

1881 | Appointment of J.A. Garfield as President, followed by C.A. Arthur. The start of the Apache War. |

1882 | Battle of Horseshoe Canyon (New Mexico). Battle of Big Dry Wash (Arizona). |

1884 | Gen. Sherman succeeded by Gen. P.H. Sheridan as General in Chief. |

1885 | Appointment of Grover Cleveland as President. |

1886 | Surrender of Geronimo. End of the Apache War. |

1888 | Death of Gen. P.H. Sheridan. |

1890 | Rise of the cult of the Ghost Dance. The battle of Wounded Knee (South Dakota). The death of Sitting Bull (15 December). The end of the Indian Wars. |

ENLISTMENT

The reasons for enlisting in the Army were almost as many and varied as the number of men who joined. There are few statistics available detailing motives for enlistment, but National Archives records show the average age of a Cavalry trooper was 23 (32 if he was re-enlisting). The background of the men does provide some clues, however. Almost 50 per cent were recent immigrants who joined the Army as a means of obtaining regular pay, an education and a grounding in the English language.

In approximate numerical order, in the ranks of the Cavalry between 1865 and 1890, could be found Irish, German/Austrian, Italian, ‘British, Dutch, French and Swiss, plus a smattering of many other nationalities. Language difficulties were a constant problem, with English-speaking immigrants often translating orders for their compatriots. Poverty, persecution and unemployment were major factors in prompting Europeans to look to America for a new life. The Potato Famine had uprooted 1,000,000 Irishmen, so it was little wonder that the Irish provided the bulk of non-American soldiery. Indeed, of the 260 men who died at Little Big Horn with Custer, approximately 30 per cent were Irish.

Many men, both officers and other ranks, rejoined the Army as a logical continuation of their Civil War service. The long war years had left them mentally unsuited to civilian life, and re-enlistment was their only option. It was these hardened veterans of Cold Harbor, Bull Run and Antietam that provided the post-war Cavalry with the disciplined backbone and experience it needed.

For many young men, the lure of the Cavalry had nothing to do with poverty, homelessness or deprivation. It was simply a case of romanticism overcoming sense. Often those who joined up came from good families and had a trade or professional qualification. Sgt. Frederick Wyllyams, who post-war joined the 7th Cavalry and had served as a volunteer during the Civil War, came from a respectable and wealthy English family, and had been educated at Eton. He was to die at the hands of Sioux warriors.

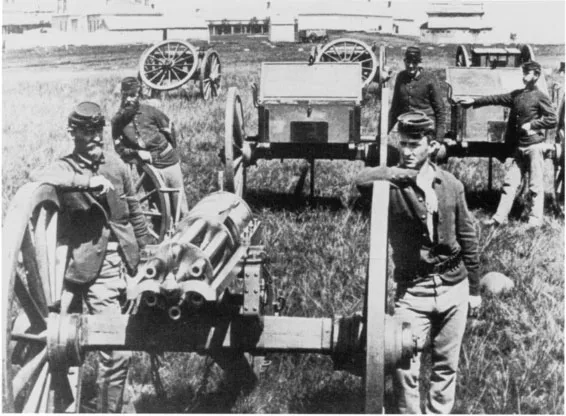

An oft-used but interesting picture of the 7th Cavalry Gatling Gun left behind by Custer. The man at the left wears a four-button sack coat with added breast pocket. The NCO behind him wears a cut-down 1861 dress frock coat. The soldier right foreground has the later five-button coat, with a homemade ‘prairie belt’, holding .45–70 ammunition. All are wearing 1872 forage caps. Taken at Fort Lincoln, Dakota, circa 1877. (Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument)

In his perceptive, contemporary book, The Story of the Soldier, Gen. George Forsyth notes a bookkeeper, farm boy, dentist, blacksmith, and ‘a young man of position’ trying to gain a commission, ‘a salesman ruined by drink, an Ivory Carver and bowery tough’ as trades once enjoyed by an escort party he was accompanying. A company of 7th Cavalry in 1877 held ‘a printer, telegraph operator, doctor, two lawyers, three language prof...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- US Cavalryman 1865–1890

- The American Plains Indians

- The Apaches

- Index