![]()

Part One

Public Enterprise and Evaluation

![]()

1

The Concept of Evaluation

The first step in an analysis of evaluation in the context of public enterprise is to be clear on the concept of evaluation. There is a wide diversity of understanding in this respect. At one extreme it is equated with the ensuring of accountability on the part of the managers entrusted with the operations of a public enterprise, as may be gleaned from the (UK) Industry and Trade Committee's reference to "the Government's belief that a public sector body which gains a considerable proportion of its revenue from monopoly activities should be properly accountable for the way in which it uses its monopoly power."1

Similar is the import of the UK Government's decision, cited in the CAG's Memorandum, that "industries not fully exposed to competition should be subjected to regular external efficiency audit."2

A few other illustrations of a relatively restrictive understanding of the evaluation concept are worth citing from the British scene. The Monopolies and Mergers Commission referred to the Audit Department of the National Coal Board as monitoring "the efficiency of the NCB's activities."3

The (UK) Transport Committee termed the work of the Serpell Committee on Railway Finances as "in essence, a management and efficiency audit,"4 and saw in it an opportunity for the Department of Trade to obtain "an independent assessment of the Board's practices in these areas."

The idea of a "customer audit" was advanced by the (UK) Post Office Users' National Council. It would be "a means of monitoring whether the customer is getting value for money," and it would be "a continuing review of the Post Office's performance."5

Emphasis on the idea of the managers performing well and of assuring the government of this can also be inferred from the conclusions of the National Economic Development Office's studies in 1976. They commented on the absence of an "external audit mechanism," "which might provide reassurance to Government and Parliament about the effectiveness of management organisation and procedures within the industry."6

The point for emphasis is not that the quest for evaluation implicit in these citations is wrong: far from it, indeed. It has a limited connotation and represents no more than a minimal element of what evaluation in the context of public enterprise ought to imply.

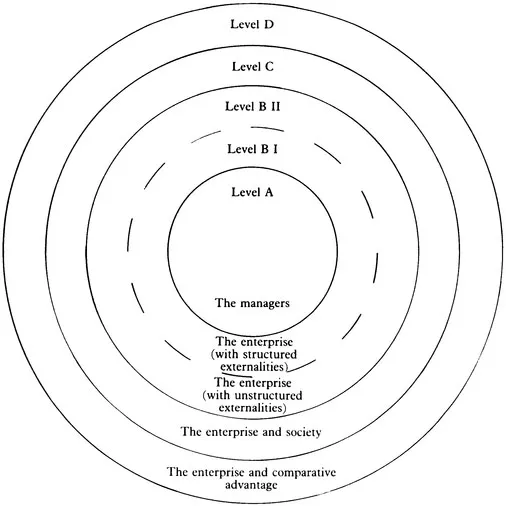

The Analogy of Concentricity

Let me develop this theme by introducing the analogy of concentricity. As shown in the following diagram (Figure 1), four levels of evaluation can be distinguished. A relates to the evaluation of the managers, Β to the evaluation of the enterprise as a whole, C to the evaluation of the compatibility of the enterprise results with social interests, and D to the evaluation of the comparative advantage of the public enterprise.

FIGURE 1 FOUR LEVELS OF EVALUATION

The simplest and minimal level is that of evaluating the managers, inclusive of the board level. Very often this is the sense in which the concept is understood. It is in that way that the government can place itself on the side of the evaluator. The idea that the managers are to be accountable for the resources and functions entrusted to them as well as the familiar term of "management audit" is traceable to this context.

There is nothing wrong about this, as already suggested. It is just not enough, even if their accountability is understood in the positive sense of maximal behaviour in the use of resources. We now go to the B-level. The performance of the managers (by whatever criteria we look at it) is the end result not merely of their own capability but of all the impacts on their behaviour from government interventions. These are of no small significance in shaping not only the final results of enterprise operations but even what appear to be managerial strategies and logistics which constitute the substance of what is sought to be evaluated at the A-level.

A few illustrations may be cited from the UK scene.

The scrutiny by the Department of Industry of the Post Office's activities is too detailed and too intrusive for a body which is supposed to be a commercial enterprise.

(Fifth Report from the Industry and Trade Committee (Session 1981-82) The Post Office (London, 1982), p. ix.)

We feel bound to conclude that the Board could have had lower costs in recent years if it had been free to pursue the objective of cost reduction by every means possible ...

The Board's procurement costs could have been lower. This arises not from lack of efficiency in use of its existing resources, but from concern on its own or the Government's part for the interests of the major suppliers.

(The Monopoly and Mergers Commission, Central Electricity Generating Board (London 1981), pp.291-2.)

The Secretary of State's decision "to retain five sites was essentially a political rather than an economic decision In our view the decision is extremely costly."

(Second Report from the Industry and Trade Committee (Session 1982-83), The British Steel Corporation's Prospects (London, 1983), pp.xi-xii.)

Apart from widening the concept of evaluation, the B-level already has a purport for who should evaluate and what that agency should seek to evaluate. Briefly, the agency has to be other than the sponsoring department of the government, and the range of evaluation has to cover the role of the government itself in the working of the enterprise. That this does not happen may be evidenced from a comment such as the following by David Chambers: "In the case of UK nationalised industries, official discussion has drawn the system boundaries very narrowly. The system to be managed is taken as the Nationalised Industry itself, not the larger configuration of the Industry, its sponsoring Ministry and the Treasury Division."7

Perhaps it is useful to distinguish between two parts of the extra-enterprise role in enterprise performance: the interventions built into formal structures, e.g., the board of directors, the issue of directives, and the established procedures of governmental communication with the enterprises; and the impacts of an informal, political and ad hoc nature. The latter may be derived from civil servants (e.g., in the course of budget discussions), from ministers (e.g., in informal meetings, if not lunches), from members of parliament (e.g., through criticism voiced in and out of the House), and from political parties (in diverse ways). These influences are difficult to establish,8 so are their impacts on performance difficult to evaluate. Yet they are too real to overlook. They may be distinguished in the Β II circle, while the "structured" interventions go into the Β I circle.

At stage C the concept of evaluation begins to be marked by a distinctive twist. The emphasis here is not on how well or ill the managers and any others who have had a role in influencing managerial behaviour performed. The aim is to evaluate what purport the enterprise results have to society.9 The point of substance is how the results agree with the interests of society. That the latter have probably not been set out in clear terms is surely a limitation on the enterprise consciously aiming to achieve a specific spectrum of results. What assumes importance at this stage of the evaluation spiral is how society reacts to whatever has been achieved by the enterprise. If one remembers that in a mixed economy, a public enterprise carries a distinctive set of macro obligations, the case for this level of evaluation can be easily appreciated. (How logically the interests of society can be identified in this connection is another question, difficult but necessary to confront, the more so in a developing country.)

Finally we come to stage D, where evaluation has to cover an adjudication of the comparative advantage of a public enterprise in respect of given sectoral operations. Far from being an inquisition into who, if at all, is to be blamed and for what, this is an approach quite essential to progress; for it allows, if not prompts, the government to gain knowledge on whether it is worth continuing with a given enterprise in the public sector, taking into account "current" market conditions and aspects of social preferences, or whether any changes in its entrepreneurial and ownership structure appear to be commendable. At the minimum, the issue can be simply this: are structural and operating changes necessary, despite continued public ownership, in order that the enterprise retains its comparative advantage? At the other end the question is whether it has sustained such a loss of comparative advantage that privatisation can be beneficial to the economy. Some rethinking on these lines is currently in progress in several developing countries, for example, Peru,10 Sri Lanka, Sudan11 and Kenya. For instance, in Kenya the Working Party on Government Expenditures in 1982 suggested that government participation in enterprises had, in several cases, reached the point where it was "inhibiting rather than providing development by Kenyans themselves." They recommended a review so as to establish, among other things, enterprises "whose functions would be more efficiently performed by the private sector."12 These views have relevance to our point under discussion, in that they underline the importance of evaluation of the D type. Were this to be in continuous progress, the implementation of policies of divestitu...