![]()

1 Faces and Cats

The faces

I would like to write - I would like to believe - that line is everything. It would make things simple. Line is how we see things. It is also how we write things: all these letters, little curly lines themselves, arranged in words and then in lines, and those lines arranged again in even neater lines on my screen, on my printout, and eventually in this book. We separate our potential knowledge of the world curricula - into subjects with lines: rather dubiously, it seems to me. In newspapers, lines separate stories from each other. Lines also supply other boundaries: between nations on the map, between religious and political beliefs.

But do we, in fact, perceive things visually, not in terms of lines, but in terms of the spaces between lines? I want to try an exercise in helping children to do this later on (the climbing frames, pp. 87-97). Paradoxically, this will make the children more certain in their perception of the lines of which the objects are, in commonsensical terms, made. Certainly, as I jot these words in the margins of my typescript on a summer evening in the garden, I am aware that if I look at the spaces between lines, or (more accurately) between the edges of things - leaves, for example - I am more aware of the things - the leaves - themselves. While discussing the illustration of children's books, Quentin Blake pointed out that the lines we see around things when we draw them do not exist. Spaces do.

Perhaps the notion of line is western European ethnocentric. In the Nigerian Yoruba culture, Emmanuel Jegede (the artist/poet/musician) once told me line is secondary to carving. It may be that some human beings perceive the world, not in terms of line at all, but in terms of depth. Maybe in western Europe we are too concerned with boundaries and edges, and not concerned enough with space, substance and density. But I am stuck with line, contentedly enough while I write this book, comforted by William Blake: 'The more distinct, sharp and wiry the bounding line, the more perfect the work of art...' (quoted in Read 1931).

I began it on an untrustworthy spring morning. The light hinted at summer and the temperature hinted at winter. After much thought, after writing a long proposal, and after planning for some weeks with Duncan, I drove the five miles east out of town to Bealings Primary School. Duncan, Pam and their colleagues are creating a little arts centre here, both in the heart of and around the edges of their school. One of Duncan's inspirations is obviously the Hepworth studio in St Ives, Cornwall - another is Kettle's Yard in Cambridge. This can best be described as an open house created by Jim Ede (one-time curator at the Tate Gallery) from almost-derelict cottages near St John's College. Its rationale - though neither its atmosphere nor the quality of what is on view - can be gleaned from the sentence 'Art [is] better approached in the intimate surroundings of a home' (Kettle's Yard 1995: 3). The house contains not just pictures and sculptures (by Gaudier-Brzeska, Hepworth and David Jones, among others) but also a collection of books, wall hangings, rugs, plants, furniture and pottery. When I try to capture the atmosphere of the house, I think of words such as 'organic'. The pieces seem to be growing in the place, cool and authentic, much as Hepworth's sculptures seem to be growing in her garden. Nothing is here merely for style, or for a thrill, or for a laugh. The house is both full of feeling, and empty of sentimentality. I rejoice in its human scale, and the evident fact that it is the home of a person who has become accustomed to look at natural objects - pebbles, for example, and shells, and wood - and to spend emotional and intellectual energy on that looking.

In Duncan's classroom (the children are aged nine, ten and eleven) there are fishing nets draped across a display of pictures and writing about the sea. There are buoys, huge waders, keepnets, and lamps. On another wall are poems written by some of the children following the study of Romeo and Juliet during one of my previous visits. On another wall are war poems, written after studying three or four of Wilfred Owen's poems, and a huge display of 'Our Images of War in the Style of Picasso' composed of visual quotations from Guernica. On another, there are imitations of Yoruba poems about twins. Like many Nigerians, Emmanuel Jegede is a twin, and the mythology surrounding that strange phenomenon fascinates me, and, using his poems, I have passed some of this fascination on to these children.

In Duncan's spacious study (spacious, that is, for a school of only 90 pupils) there is a large, low, square, wooden table in the middle. His neat desk is pushed to one wall. Dried plants as tall as me firework out of ceramic pots in two corners of the room. There is an eclectic collection of recent books about teaching. He had, he told me, given each teacher a budget to buy books that appealed to them. The usual statutory files, from central government and from the local authority, look neat and undisturbed in one corner. I disturb one. Moving Language Forward (or something like that) is depressingly mechanistic. It is full of tables representing levels, and the only children's writing that I can see are letters, or that weak, problematic genre foisted on children these days by successive governments, 'writing to persuade'. On the walls of the room are examples of children's work - imitations of Modigliani, for example - and reproductions of modern art.

Duncan enthused about a future project involving visiting poets, artists and dancers. He can afford this project (and this enthusiasm) because Bealings is now 'a beacon school', and will be receiving money to finance such initiatives. Other schools in the county that are - according to inspections, test results, league tables and the like - less successful than Bealings will be involved in the project.

I asked the seven-, eight- and nine-year-old children to draw friends' faces. Drawing is an important way (conventionally underrated by managers in education, i.e. politicians, advisers and inspectors) in which we can rediscover, almost at will, the world in which we live. Even more importantly, as we draw, we build a bridge between ourselves and our world. Thus drawing strengthens our position in the world, and our grip on that world.

Not teaching the faces

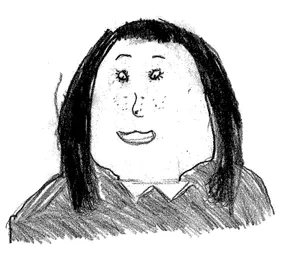

Here are three examples, by Anna, Rosemary and Lindsay (Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3). These drawings are ordinary. Similar work can be found in decent schools all over the country. These pictures were done without any teaching, or more accurately, they were done without any teaching immediately before the children worked. The school's tradition of teaching art is strong, as I have shown, and that tradition obviously informed what the children did on this occasion. There had been, so to speak, long-term teaching: witness the relationship with St Ives and the resultant gardens and the sculptures. But there had been no short-term teaching. The deliberate avoidance of teaching on that morning (not, I found, easy to do) reminded me of an orthodoxy among some teachers 20 years ago. Teachers should not teach, but be 'enablers of learning'. They should 'provide an environment that helps children to discover for themselves what they need to know when they are ready for it'. I understood then - and understand now - the motivation for such thinking. It aimed at offering an education that set the children free to discover their world and their relationship to it. But it neglected how much the teacher has to do in both talking and listening to the children. I appreciate now that this notion can be seen as a sentimental evasion of responsibility.

With these children I took the no-teaching rule literally: 'Just draw your friend's face.' It was so far from teaching that it was merely instruction, or even the giving of an order (although that, I know, is not what the sixties progressives meant). I let the children do what they wanted: they drew tentatively, then rubbed lines out, feverishly, as though the rubbing out meant more that the lines themselves. I let them, if they wanted, cover no more than the corner of their sheets of A4 paper. I didn't interrupt them with requests that they 'look harder', and I didn't worry them with suggestions about how they might get their pencils to make different kinds of mark.

Anna's drawing (Figure 1.1) has attempts at accuracy in it, but is static and dull. Rosemary's drawing (Figure 1.2) is the smallest of the drawings, and more interesting than the other two: a hint of the cartoon (Posy Simmonds' dowdier women, in Guardian strips perhaps?) lurks in there somewhere. Lindsay's drawing (Figure 1.3) had life from the beginning, partly because she noticed that Hannah was looking at her in order to draw her. Hence that sidelong glance: the girls were sitting side by side.

Teaching the faces

I then taught the children in an old-fashioned instructional way. I give here the notes of my lesson (in bold type as these four rules constitute the basic building blocks of this book).

- 1. no erasers

- 2. close-up

- 3. making different kinds of pencil mark

- 4. look look look (quote Blake and Tardios)

I had taught in this way many times before and those bare notes were all I needed. Expanded they look like this, much like notes I prepared on my first teaching practice 30-odd years ago. They are merely notes to myself but expanded to include objectives. Objectives post-dated my college days and I came to distrust them. This is because to focus on the future, on what children might achieve one day, is to play down first, what they are now, and second, the teacher's creativity. But I include them because they are now part of the everyday currency of teaching.

Teaching objectives

- To help the children to look closely

- To help them to transfer the results of their looking to their drawing

- To help them to learn about the appearance and structure of the human face

- To help them make a work of art

Process of the lesson

The children may not use erasers. Point out the importance of keeping 'first thoughts', as in drawings by Giacometti and others. Tell the children that 'wrong lines might come is useful later - please leave them there and then do the right line, or even another line that seems even more right'.

Ask the children to draw subjects 'close-up'. Tell them little tiny images in the corner of the paper won't be much help. 'Perhaps you could draw your subject so close-up that it won't fit on the page. I want your drawings done so that I can see the details.' Don't just say you want 'big drawings'.

Ask the ch...