eBook - ePub

Greening Trade and Investment

Environmental Protection Without Protectionism

This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A comprehensive, critical analysis of the interactions between investment, trade and the environment. It examines the consequences of existing multilateral investment and trade regimes, including the WTO and the MAI for the environment, and asks how they should be reformed to protect it. In doing so, the text shows how these regimes can be greened without erecting protectionist barriers to trade that frustrate the development aspirations of poorer countries. The solution seeks to offer a way out of one of the most difficult dilemmas in international policy: how investment and trade can protect the environment without encouraging protectionism by the industrialized world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Greening Trade and Investment by Eric Neumayer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Foundations

Part One provides the foundations for the main analysis that follows in Parts Two and Three. It is written for those who are unfamiliar with the major issues. Chapter 1 puts the discussion into historical context in illuminating the development of trade integration and investment flows from about 1870 to 2000. It also introduces the main institutions and agreements encountered in the book. Finally, it examines why developing countries are so hostile towards greening the multilateral investment and trade regimes in the context of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Meeting in Seattle in late 1999 and the failed attempt to launch a new ‘Millennium Round’ of trade negotiations.

Chapter 2 looks at the current regulatory regime in presenting the major rules of the multilateral trade and investment regimes with respect to the environment. The main analysis in Parts Two and Three will frequently refer back to these rules. However, the reader who is familiar with the multilateral trade and investment regimes may omit Chapters 1 and 2, or consult various sections and subsections only.

1

Globalization: Investment, Trade and the Environment in an Integrating World Economy

Trade integration and investment flows in historical perspective

A defining character of the 1990s has been the continuation and strengthening of what has become known as economic globalization: international trade has grown faster than world economic output in every decade after 1950, and since around the mid-1980s foreign direct investment (FDI) flows are growing faster still on average than international trade flows (UNCTAD 1993, Annex Table 1; UNCTAD 1994, p127; UNCTAD 1998a, Annex Table B.1). Indeed, whereas the difference in growth rates of world trade and world output had decreased in each decade since the 1960s, the last decade of the 20th century has seen a sharp increase in this growth differential (UNCTAD 1991, 1995, 1998cc). As a consequence, the economies of nation states all over the globe are becoming integrated at a high pace.

At the same time, however, the extent to which international economies are already interlinked is often exaggerated. For example, the exports share of gross domestic product (GDP) was about 7.6 per cent for the US in 1996, 9.3 per cent for Japan and 21.3 per cent for Germany (UNCTAD 1999b; OECD 1999b). While the speed of integration is fast and accelerating, it is still at a relatively low level and it is unclear for how long it can prolong its own momentum into the future.

It is sometimes even suggested that what we describe as economic globalization nowadays has already been a defining character of the period 1870–1913, when world gross product grew at an average annual rate of 2.5 per cent, while world trade increased at 3.9 per cent and international flows of capital grew significantly – now, as then, made possible by tremendous falls in transportation and communication costs (see Maddison 1991;

UNCTAD 1994, pp120–122). Sachs and Warner (1995) suggest that:

… global capitalism has emerged twice, at the end of the nineteenth century as well as the end of the twentieth century. The earlier global capitalist system peaked around 1910 but subsequently disintegrated in the first half of the twentieth century, between the outbreak of World War I and the end of World War II. The reemergence of a global, capitalist market economy since 1950, and especially since the mid-1980s, in an important sense reestablishes the global market economy that had existed one hundred years earlier (p5, emphasis in original).

The system was highly integrative, as in the present. A network of bilateral trade treaties kept protectionism in check in most countries (the United States and Russia, where tariff rates were relatively high, being the exceptions). Nations as diverse as Argentina and Russia struggled to adjust their economic policies, and especially their financial policies, to attract foreign investment, particularly for railway building (p8).

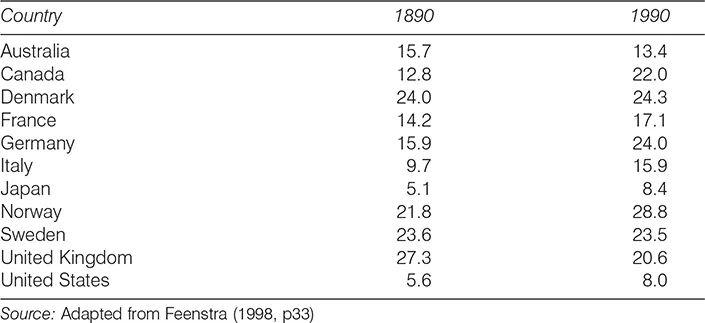

Bairoch and Kozul-Wright (1996) actually doubt the validity of the historical analysis provided by Sachs and Warner (1995) in support of their claims, arguing forcefully that continental European countries already became highly protectionist after 1879 and that most non-European advanced countries never adopted a liberal trade regime at all. However, here we will merely further examine the question whether the world about one century ago had the same or at least a very similar extent of trade integration as the current world. At first sight, the available historical data seem to support such an inference – see Table 1.1 adapted from Feenstra (1998, p33). Countries like Australia, Sweden and the UK had a higher ratio of merchandise trade to GDP in 1890 than in 1990. For others, like Japan and the US, the 1990 ratio is not that much higher than the 1890 ratio.

However, to conclude from these historical data that in terms of trade integration current economic globalization is merely a revival of a similar phenomenon from about a century ago would be too hasty because it might be misleading to focus on the trade to GDP ratio, as GDP includes many sectors that do not enter the merchandise trade statistics. As Irwin (1996, p42) points out:

When GNP1 is disaggregated by industry, it typically includes the following sectors: agriculture (including forestry and fisheries); mining; construction; manufacturing; transportation and public utilities; wholesale and retail trade; finance, insurance, and real estate; other services; and government. Of these categories only agriculture, mining, and manufacturing really produce merchandise goods that enter into standard trade statistics. Over the past few decades, the sectoral composition of nominal GNP has shifted away from the production of merchandise goods toward the production of services.

Table 1.1 Ratios of merchandise trade to GDP in per cent

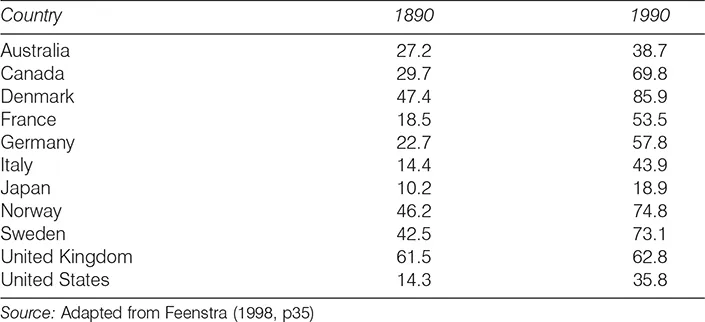

He therefore concludes that ‘[P]erhaps a better indication of the importance of international trade is to consider merchandise exports as a share of the production of these tradable goods’ (ibid). Table 1.2, taken from Feenstra (1998, p35) shows the ratios of merchandise trade to merchandise value added. As can be seen in comparing Table 1.2 to Table 1.1, for most countries the increase in the ratios of merchandise trade to merchandise value added between 1890 and 1990 is much more significant than the increase in the ratios of merchandise trade to GDP over the same time period.

As with trade integration, some have doubted whether current international flows of investment are significantly higher than what they were in the period before 1913. According to Bairoch and Kozul-Wright (1996, p11), in terms of international capital flows, by 1913 about 5 per cent of the gross national product (GNP) of the capital exporting countries was invested abroad, mostly into railways, utilities and public works, and international capital markets were integrated to a considerable extent. Baldwin and Martin (1999, pp10ff) claim that foreign investment was more long-term oriented than in the current phase of globalization, however, due to the much higher costs of communication which hindered the rapid movement of highly liquid investments.

The period before 1913 knew already the phenomenon of TNCs – for example, the famous East India Company – and foreign investment was growing rapidly, with FDI amounting to one-third of overseas investment. Bairoch and Kozul-Wright (1996, p10) point out that their ‘own estimate suggests that the stock of FDI reached over 9 per cent of world output in 1913, a figure which had not been surpassed in the early 1990s’. However, the 1980s and 1990s have seen a tremendous increase in foreign investment. The worldwide inward FDI stock has increased from 4.6 per cent of world GDP in 1980, to 6.5 per cent in 1985, 8 per cent in 1990 and 10.6 per cent in 1996 (UNCTAD 1999a, Statistical Annex, Table B.6). International private flows of financial resources have increased from US$33 billion in 1986 to US$252 billion in 1997 (OECD 1988, Statistical Annex, Table 12; OECD 1999a, Statistical Annex, Table 1).

While the rather volatile and often speculative portfolio equity flows have risen at a tremendous speed in the early 1990s, still more than 50 per cent of private flows consist of FDI and about 15 per cent of commercial bank loans (UNCTAD 1998a, p14).2 Contrary to the first phase of globalization when FDI mainly flew from advanced countries to more backward countries and mainly into their primary and transportation sectors (Baldwin and Martin 1999, pp18ff), the developed countries are now both the dominating source and the major recipient of FDI, and investment mainly flows into the manufacturing and services sector. However, the dominance of developed countries in terms of FDI recipients has decreased over time, with developing countries in the 1990s receiving almost 40 per cent of FDI as opposed to only about 20 per cent in the 1980s (UNCTAD 1993, Annex Table 1, and UNCTAD 1999a, Annex Table B.1). Indeed, FDI inflows per unit of GDP are much higher in developing as opposed to developed countries. While the latter received FDI in 1996 of around 10 per cent per unit of output, Africa receives 13.7 per cent, Latin America and the Caribbean 23.7 per cent, South, East and South-East Asia 27.5 per cent, and Central and Eastern Europe 15 per cent (UNCTAD 1998a, p10). There was only one developed country (New Zealand) among the top 30 recipients of FDI inflows as measured per unit of GDP (ibid, p11).

Private international flows of financial resources have become increasingly important to developing countries as official development assistance from the developed world has dried up because of tight budgets and a decreased willingness to assist. The official development assistance (ODA) share of the total net resource flows to developing countries has decreased from 64.1 per cent in 1988 to merely 23.6 per cent in 1997 (OECD 1999a, Statistical Annex, Table 1). It is often asserted, however, that contrary to the ODA international investment flows benefit mainly about a dozen developing countries in Asia and Latin America, whereas the vast majority of poor countries, especially in Africa, are left out. This assertion is correct in the sense that countries like Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Venezuela in Latin America, and China, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and India in Asia, together received almost 72 per cent of all the FDI flowing to the developing world in 1998 and more than 40 times more than the combined FDI to all of the least developed countries together (UNCTAD 1999a, Annex Table B.1). However, the picture is much less uneven if FDI is looked at as a percentage of gross fixed capital formation rather than as absolute figures. This percentage was 8.3 for Africa in 1997, only slightly lower than the developing countries’ average of 10.3, and higher than either India’s (4.2) or Thailand’s (6.8) (UNCTAD 1999aa, Annex Table B.5).

Table 1.2 Ratios of merchandise trade to merchandise value-added in per cent

It is true that a large share of FDI inflows to developing countries consists of cross-border mergers and acquisitions rather than the setting up of a new plant by a transnational corporation (TNC). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (1998a, p19), the share of mergers and acquisitions has been on average about 50 per cent of FDI inflows between 1985 and 1997. This need not be bad for developing countries, however, as the inflow of capital into existing companies together with their restructuring typically leads to efficiency and profitability improvements.

The expansion of private investment flows has been accompanied by policy changes towards a more investment-friendly environment that makes countries more receptive for these flows. The relationship between the economic and political dimension is not fully clear, but changes in both dimensions seem to have gone hand in hand and to have mutually enforced themselves. According to UNCTAD (1998a, p57), since 1991 on average about 50 countries each year enacted on average about 100 regulatory policy changes every year, the vast majority of which were favourable towards FDI. However, because competition for scarce financial resources is tough and countries fear to lose out in the bid for foreign investment, the last 15 years or so have also seen an increase in incentives that are supposed to lure investment, especially FDI, into a specific location rather than elsewhere. An UNCTAD (1996, p17) study comes to the conclusion that ‘the range of incentives available to TNCs, and the number of countries that offer incentives, have increased considerably since the mid-1980s, as barriers to FDI and trade have declined’.

The proliferation and inflation of these incentives are often regarded as socially wasteful as in general they do not increase the overall amount of FDI available, but merely distort the efficient allocation of flows among recipient countries.3 Investments still flow to the location with the highest return on investment; however, this return is not fully justified by economic productivity but artificially created via governmental incentives, financial or other. Countries are caught in a so-called Prisoner’s Dilemma where all would be better off if nobody granted the incentives, but everybody fears to lose out if only the others grant them, so that all end up providing incentives, thus making everybody worse off. The World Trade Organization (WTO) (1998g, p17) makes clear why such a Prisoner’s Dilemma is undesirable:

The lasting effect is only to redistribute income from host countries to the shareholders of the home countries. This has negative repercussions on global income distribution since some of the gains that would have accrued to poorer developing countries (that are net recipients of FDI) are squandered on incentives to richer developed countries (that are net outward investors).

It does not matter much that studies of the determinants of FDI flows generally indicate that incentives have only a very minor role to play in international investment decisions (UNCTAD 1996, p41; WTO 1998g). This is for two reasons: first, these incentives can make a difference at the margin, and second, and more importantly, what matters is that, against the received wisdom of empirical studies, policy-makers apparently do believe in the power of incentives to attract investment.

To conclude, while it is often overlooked that the world economy before 1913 was already integrated significantly both in terms of trade and investment flows, the current extent and pace of trade and investment integration seem to signify that the world has entered an unprecedented phase of what is commonly described as economic globalization. Investment and trade do matter and will do so more and more. Next we will briefly present how the creation of a multilateral trade regime has helped to bring about economic globalization and how in turn it has been influenced by globalization, as well as how the links between investment, trade and the environment were addressed.

The institutions governing economic globalization

GATT, ITO and WTO

When a couple desperately want to have a baby girl, but have a boy instead, the parents usually accept the child after their initial disappointment. In some sense, in 1947 the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) resembled such a baby boy: it was not exactly what its founding countries wanted to have, but they settled for it for lack of an alternative.

What was originally envisaged by over 50 countries was a sister organization for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, nowadays better known as the World Bank) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which are called the ‘Bretton Woods’ institutions because they were founded in 1944 at a conference in the town of Bretton Woods in the US state of New Hampshire. This envisaged sister organization already had a name, International Trade Organization (ITO), and was supposed to be a specialized agency of the United Nations. It was also supposed to be a comprehensive organization with extensive competences for the regulation of world trade in products and services, and international investment, as well as for commodity agreements, restrictive business practices and employment rules. Its charter was finally agreed upon at a UN Conference on Trade and Employment in March 1948 in Havana, which is why it is commonly referred to as the ‘Havana Charter’. However, ratification of the charter proved to be impossible in many countries. Most importantly, the US government, which had been one of its strongest proponents, announced in 1950 that its ratification in the US Congress would be impossible, which gave the final death blow to the ITO. Right-wing critics saw too many elements of economic planning, for example in its call for action to maintain full employment in its Article 3, and a sacrifice of US principles and interests in the charter (Brown 1950). One critic went as far as calling it a threat to human freedom and an ‘economic Munich’, alluding to the de facto resignation of the English democracy to the expansionary aggression of the Nazi regime against the Czechs in 1938 (Cortney 1949).

Enter the GATT. Two years before the Havana conference, 23 of the 50 countries that participated in the ITO negotiations had started negotiations on the reduction and binding of customs tariffs. These, together with some of the trade rules of the draft ITO charter, formed the G...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- contents

- List of Tables and Boxes

- preface

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part One Foundations

- 1 Globalization: Investment, Trade and the Environment in an Integrating World Economy

- 2 The Current Multilateral Trade and Investment Regimes

- Part Two Investment

- 3 Pollution Havens: Do Developing Countries Set Inefficient Environmental Standards to Attract Foreign Investment?

- 4 Regulatory Chill: Do Developed Countries Fail to Raise Environmental Standards Because of Feared Capital Flight?

- 5 Roll-back: Do Foreign Investors Use Investor-to-State Dispute Settlement to Knock Down Environmental Regulations?

- 6 A Case Study: The Failed Attempt to Conclude a Multilateral Agreement on Investment

- Part Three Trade

- 7 Trade Liberalization and the nvironment

- 8 GATT/WTO Dispute Settlement and the Environment

- 9 WTO Rules and Multilateral Environmental Agreements

- 10 Conclusion and Summary of Policy Recommendations

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index