![]()

PART I

WOMEN, ENVIRONMENT

AND NATURAL RESOURCES

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Why Women?

The role of women is crucial in meeting the big crises of the world today (Fresco, 1985:24).

It is difficult to talk about women as a whole without ignoring the vast economic, cultural and social differences between them. Even if we were to consider only women in the Third World, we would find it difficult to generalize. The lives of women in India, for instance, are different from those in Ghana or Peru; and within countries, similar gaps in income and culture exist.

Nevertheless, it is possible to outline the general shape of women’s living conditions in the rural areas of the Third World. They share, first of all, their poverty: roughly 75 per cent of the world’s population are among the poorest, and women make up the majority of the poor. Secondly, wherever they live, they are bound together by the common fact of their tremendous work burden. Time-budget studies show that women not only perform physically heavier work, but also work longer hours than men. In Tanzania women work an average of 3,069 hours per year; men work an average of 1,829 hours (Taylor et al., 1985). In Bangladesh it has been estimated that women spend an average of 10–14 hours per day on productive labour. Household tasks are not taken into account in this estimation.

An Indian agricultural worker’s day is typical. She rises at 4 a.m. She cleans the house, washes clothes, prepares the meal for her husband and children, and leaves for the fields at 8 a.m. She works there until 6 p.m., in the meanwhile nursing the small children she took with her. On her way back home she collects fuelwood, and, if necessary, drinking water. She cooks the evening meal, cares for the children and tends to the animals. At about 10 p.m. she goes to bed. On such a day she might earn less than two rupees.

Like this Indian woman, rural women have traditionally been the invisible workforce, the unacknowledged backbone of the family economy. Men go out to work, enter into commerce, make the decisions in the village and household, and are more likely to be chosen as spokespersons when it comes to dealing with government or development agencies. But when we look more closely at the types of work that women do, we can distinguish three main areas, all crucial to keeping the family and indeed the rural economy alive. These three areas are: survival tasks, work in the household, and income generation.

SURVIVAL TASKS

Survival tasks are those essential for daily life, and it is for these that women are largely responsible. They grow the food crops, provide water, gather fuel and perform most of the other work which sustains the family. A 1985 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization study indicates that in some Third World regions, especially in Africa, women account for 80 per cent of agricultural production. And women’s involvement in food-growing is increasing steadily. In Malawi in 1966, women accounted for less than 70 per cent of the agricultural labour force. By 1972 this figure had risen to 90 per cent.

A certain division of labour is evident in the agricultural sector. Women are generally responsible for sowing, weeding, crop maintenance and harvesting, as long as these tasks have not been mechanized. Men, on the other hand, look after field preparation. Subsistence agriculture – the growing of food crops – is almost exclusively a women’s task. But women’s participation is increasing in cash-cropping as well. Care of small animals is also often their responsibility.

The supply of water – vital for the survival and health of the family and for farming – is exclusively the concern of women and children. A study in East Africa showed that carrying water can use 12 per cent of the calorie intake of women, and, in dry and steeper areas, up to 27 per cent. In a village close to New Delhi, water collection takes an average of an hour each day. But as Chapter 3 of this book shows, collecting water can take a lot longer, and each load can weigh as much as 25 kilograms.

For their energy supplies, the rural areas of the Third World depend mainly on biomass such as fuelwood, crop residues and manure. Seventy-five per cent of rural energy supplies (and 90 per cent in Africa) come from biomass. Fuel collection, where it is not commercialized, is mainly a task for women, with children’s help. Depending on the ecological characteristics of the area in which they live, women may spend up to five hours a day on fuel collection. The relationship between these survival tasks and the ecological situation is described in coming chapters.

HOUSEHOLD TASKS

Activities in the home are almost exclusively the responsibility of women, although older children may occasionally assist. These tasks return every day and absorb hours of time. Food preparation and cooking are a good example. In a study area in Peru, an average of four hours every day are spent on cooking (ILO, 1986). Yet women in many cultures are often the last in the family who may eat, and they take less than the other family members.

WOMEN’S INCOME

Throughout developing countries, women contribute substantially to the family budget through income-generating activities – food processing, trading of agricultural products and the production of handicrafts. This is particularly the case for the growing number of female-headed households where men have migrated to cities, mines, plantations, or abroad. A recent survey shows that the percentage of female-headed households south of the Sahara in Africa is already 22 per cent; in the Caribbean area 20 per cent; in India about 19 per cent; in the Far East and North Africa 16 per cent; and in Latin America 15 per cent. Locally much higher percentages can be found where women are the sole providers. Even where a woman is not completely alone, her contribution to the budget is of utmost importance to the family, the more so because women spend more of their income on family welfare.

It is clear that women fulfil a great number of essential tasks, yet they and their labour are often unrewarded. “Although women represent half of the world’s population and one-third of the official labour force, they receive only one per cent of the world income and own less than one per cent of the world’s property” (UN Conference, Copenhagen, 1980). Notwithstanding their important role, women have only very limited access to and control over income, credit, land, education, training and information.

Recent developments have worsened the position of women: Western colonization, the increasing dependency of Third World countries on a Western monetary economy, developments in technology such as agricultural modernization, the sharpening worldwide division of labour, and increasing religious fundamentalism have all brought extra problems for women. The accelerating degradation of the living environment is the latest and, in many ways, the most dangerous of the threats they face.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

Land: Women at the Centre of the Food Crisis

Land, particularly healthy soil, is the foundation on which life depends. If the land is healthy, then agriculture and pasturage will yield food in plenty. If it is not, the ecosystem will show signs of strain and food production will become more difficult. Because women are at the centre of world food production – producing more than 80 per cent of the food in some countries – any analysis of land resources must include an appreciation of their central role.

LITTLE FOOD, NO LAND

The present world food situation is one of the great modern paradoxes: about 500 million people – the largest number ever – are seriously malnourished while world food production has reached the highest levels in history.

Hunger in the Third World is not necessary. Official Food and Agriculture Organization projections show that the earth can provide more than enough food not only for our present population of 5,000 million, but also for the 6,100 million people expected by the year 2000 (FAO, 1981). But these numerical calculations do not take account of the problems of food distribution, of economic control over food resources, and the politics of food dependency. Access to food is not simply a question of land availability, but of social, political and economic power. The poor have none of these.

Expanding cropland will offer only a limited solution to the landlessness of the poor. Success would depend upon good-quality land being available to those most in need. Of the world’s 13,250 million hectares of land, about 30 per cent is estimated to be arable, half of which is now under cultivation. Just over half of the land presently under cultivation is found in developing countries, but it is inhabited by three-quarters of the world’s population. Within countries, there is severe inequity of land ownership (see figure 1).

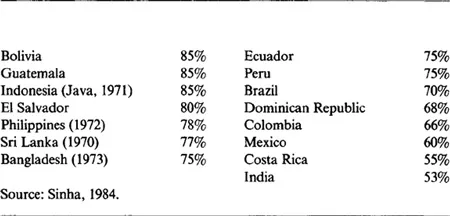

Figure 1: The landless and near-landless as a percentage of total rural households

Even with the initiation of agrarian reforms, the politics of land ownership often work to ensure that the most productive land remains in the hands of a few. Where political power resides with a land-owning élite, governments allow private estates to expand further and protect their boundaries. In Colombia, land reform has meant the modernization and capitalization of existing estates, leading to even greater concentration of ownership (Leon de Leal, 1985). In El Salvador, the land reform of 1980 brought no significant change in the plight of the country’s 2.5 million landless or near-landless peasants (Pearce, 1986). Here, as in many Third World countries, the poorest are squeezed on to marginal lands which are steep, infertile, dry, subject to pests or disease or covered with rainforest. Their attempts to grow subsistence crops result only in increased erosion and the destruction of water and fuelwood resources. Where many people are forced on to poor land, fallow periods diminish or disappear and the possibilities for soil recovery are reduced. Scarce energy sources cause people to burn manure and crop residues to meet their fuel needs, and the loss of these traditional sources of soil nutrients decreases land fertility. It is estimated that the annual burning of 400 million tonnes of dung depresses the world’s grain harvest by over fourteen million tonnes (Spears, 1978).

Women produce food

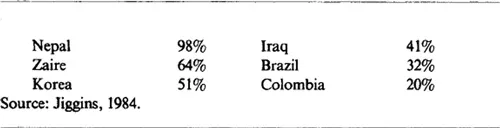

Many of those dispossessed of land by the increasing concentration of ownership are women and their children. Women have title to only one percent of the world’s land. Yet they produce more than half of the world’s food – and in countries of food scarcity the percentage is even higher. Women produce more than 80 per cent of the food for sub- Saharan Africa, 50–60 per cent of Asia’s food, 46 per cent in the Caribbean, 31 per cent in North Africa and the Middle East and more than 30 per cent in Latin America (FAO, 1984; Foster, 1986).

Women make up the majority of subsistence farmers. In most rural cultures, it is their work which provides a family with its basic diet and with any supplementary food that may be obtained from barter or from selling surplus goods. Underestimating the amount of agricultural work done by women is very common, for statistics most often measure wage labour, not unpaid kitchen garden work. Moreover, in some cultures men do not wish to admit that their wives, mothers and daughters do agricultural work. For these reasons, the vital contribution that women make to food production is consistently under-represented (Taylor et al., 1985).

Women also participate actively in cash-crop production, either as extra hands at harvest time or as employees on large farms. Women can sometimes spend more time in export production than men. In Nigeria, for example, women work more than men in the cocoa plantations, in coffee production for export, and in national market crops such as rice, grain, maize and cassava (Fresco, 1985). In Nicaragua in 1980, women made up 28 per cent of coffee harvesters and 32 per cent of cotton workers (IFDP, 1980).

MORE TECHNOLOGY, LESS SOIL FERTILITY

Increasing agricultural industrialization, particularly under the “Green Revolution” introduced in the 1950s, has had an enormous effect on women. This policy of intensifying food production through developing hybrid, high-yield seed varieties demanded extensive irrigation and increased mechanization, as well as the use of fertilizers and pesticides. Chemical and biological technology was applied on a large scale in South-East Asia, India, China and Mexico, with the goal of increasing food production. Yields did increase, often dramatically. Between 1974 and 1983 they grew at more than two per cent each year - largely as a result of the increased productivity of land already under cultivation. But in spite of this increase the people of South-East Asia and India are still among the least well-nourished in the world. The Green Revolution has produced no increase in per capita food consumption and has in many cases reduced it (Lappé and Collins, 1986). Instead, the Green Revolution has contributed to erosion, desertification, and greater concentrations of land ownership, removing land from those most in need.

Figure 2: Percentage of total agricultural production by women

Erosion and desertification are not merely a result of rainfall:

Only appropriate land use can keep arid zones ecologically stable and biologically productive. Inappropriate land use can destabilize even humid regions, undermining biological productivity and causing desertification. Since the large majority of people in countries like India have livelihoods based on land, the long-term decline of the biological productivity of land undermines livelihoods and results in underdevelopment (Bandyopadhyay and Shiva, 1986:1).

Large-scale, mechanized, highly-technological agriculture is extremely taxing on land fertility. Widespread irrigation – probably the most effective way to increase yields – can cause waterlogging, a reduction of essential minerals, and salinization because of increased evaporation. More than a third of all land under irrigation is subject to salinization, alkalinization and waterlogging (UNEP, 1982). In some areas, 80 per cent of the irrigated land has been destroyed in these ways. Worldwide, salinization alone may require the abandonment of as much land as is now under irrigation (World Resources, 1986).

Synthetic petroleum-based fertilizers are also the cause of serious soil and water pollution. Experiments show that this kind of agriculture affects the metabolic balance in plants, leaving them more vulnerable to attack from pests and diseases. Farmers are then caught in the vicious circle of increasingly intensive (and costly) use of pesticides which in turn causes greater pest infestation (Guazzelli, 1985). There is growing concern over the developing immunity of many pest species as pesticide use accelerates, especially in developing countries.

Pesticide use also has serious consequences for health. During informal consultations in 1985, the World Health Organization estimated that one million cases of pesticide poisoning occur annually.Not only human beings, but many other non-target species (and livelihoods based on them) are affected by pesticide poisoning, including livestock, fish, birds and bees (Bull, 1982).

The introduction of laboratory-bred hybrid crop species has also had negative consequences. In the district of Dharwar, India, for example, a mix of indigenous varieties of crops were cultivated, giving high yields of fodder, pulses...