![]()

1

Introduction

Flying into São Paulo on a clear day, one can easily understand why this city has been called the locomotive that pulls the rest of Brazil. With a population in excess of 15 million, it is the largest city of the Southern Hemisphere. From its center thrust impressive clusters of modern buildings; beyond them the metropolitan complex stretches as far as the eye can see. This is the foremost industrial center of Latin America, and a dominant presence in finance and trade. São Paulo is home to Brazil’s automobile industry, and accounts for much of its manufacturing in sectors as diverse as computers, electrical and mechanical appliances, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, textiles, furniture, and processed foods. With about one-tenth of Brazil’s population, the city generates one-third of the country’s net national product. In addition to being an economic powerhouse, São Paulo is a force in culture and intellectual debate, the site of four universities, a medical school, and many important museums. In economics, politics, and the arts, writes Alves (2003), “São Paulo has become an exporter of ideas.”

This is a bird’s-eye view of the city, but on closer inspection São Paulo takes on a more variegated appearance. It can be seen that poor neighborhoods and ramshackle housing surround some of the high-rise commercial clusters. Consider the situation of Marta, a young woman who lives in one of these favelas. Her husband once held a steady job in a manufacturing firm, but lost it in the economic downturns of the 1980s and now ekes out a living as a security guard for a rich family. Marta herself takes in work as a seamstress, but she keeps an eye out for any opportunity that might come her way. She is pleased that her daughters are about to complete primary school, unlike their cousins in the countryside who dropped out. Still, she worries incessantly about the children’s safety, especially since their route to school wends through territory claimed by rival gangs. Marta’s aunt, a formidable nurse in a clinic not far away, continually impresses upon her the need for the children to be well educated, but in looking ahead, Marta finds herself wondering whether the girls would really benefit from secondary school. The pros and cons of schooling are much debated among her friends, some pointing to success stories and others to children who wasted their education; they all complain, however, about the difficulties and costs of rearing children properly in São Paulo. Marta’s friends are unanimous on one point: to have five or six children today, as was often done in their mothers’ time, would be too exhausting even to contemplate.

In vignettes such as this, the positive and negative elements of urban life are thoroughly intermixed. Cities are the sites where diverse social and economic resources are concentrated, and that concentration can generate substantial economic benefits in the form of innovation and income growth (Jacobs, 1969; Glaeser, Kallal, Scheinkman, and Shleifer, 1992; Henderson, 2002). If cities could not offer such benefits, they would have little reason to exist, for the massing of production and population also generates many costs—heavy congestion, high rents, and stress on the capacities of government. In the nineteenth century, this opposition of benefits and costs was well understood. The cities of that time were likened to “satanic mills” where one could seize economic opportunity only at some risk to life and health. In much of today’s popular writing on cities, however, the costs of city life tend to be vividly described, while the economic benefits are left unmentioned.

Cities are also the sites of diverse forms of social interaction, whether on the staging grounds of neighborhoods, through personal social networks, or within local community associations. The multiple social worlds inhabited by city residents must profoundly influence their outlooks and perceptions of life’s possibilities. In city life, many family productive and reproductive strategies are on display, with the consequences being acted out by local role models and reference groups. The poor are often brought into contact with the near-poor and sometimes with the rich; these social collisions can either stir ambitions or fan frustrations. The social embeddedness and multiple contexts of urban life (Granovetter, 1985) would thus appear to present demographic researchers with a very rich field for analysis.

Over the past two decades, researchers interested in high-income countries have moved to take up this analytic challenge, with much of the intellectual energy being provided by the powerful writings of Wilson (1987) and Coleman (1988, 1990) on the roles of neighborhoods and local context in the cities of the United States. But the cities of poor countries have seen no comparable surge in demographic research. Indeed, apart from the occasional study of migration, the mainstream literature has been all but silent on the demographic implications of urban life in developing countries. Not since Preston (1979) and the United Nations (1980) has there been a rigorous, comprehensive assessment of urban demography in these countries.

As we will discuss, the U.S. literature has emphasized many of the themes that are of central importance to the cities of low-income countries: children’s schooling, reproductive behavior among adolescents and adults, health, spatial segregation, and employment. It has also advanced important theories and mechanisms—social learning, networks, collective socialization, and social capital among them—that have clear parallels in developing-country cities. Yet, at least to date, the theories and research strategies being vigorously pursued in the U.S. context have not been taken up elsewhere. On these grounds alone, a review of what is known about urban population dynamics would appear well overdue.

This chapter introduces some of the themes that will be explored in the chapters to follow, together with basic demographic information on the urban transformation. The chapter also describes the panel’s charge, the main reasons for undertaking this study, and some of the major audiences for the report, with particular reference to the demographic research community.

THE DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSFORMATION

The neglect of urban research can only be reckoned astonishing when considered in light of the demographic transformations now under way. The world’s population passed 6 billion in 1999, and 6 of every 7 people now reside in a low- or middle-income country.1 The global rate of population growth has declined over the past 20 years; in absolute terms, however, the world remains in the midst of an era of historically dramatic population increase. According to the latest United Nations (2002a) projections, even as the rate of population growth continues to decline, the world’s total population will rise substantially. The total is expected to reach 8.27 billion in 2030, this being a net addition of 2.2 billion persons to the 2000 population. Almost all of this growth will take place in the poor countries of the world, whose governments and economies are generally ill equipped to deal with it.

The Urban Future

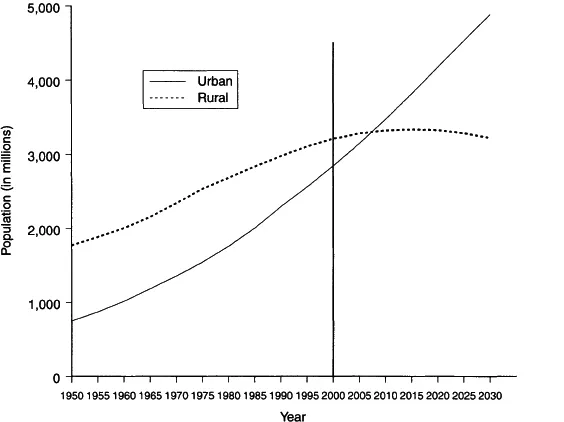

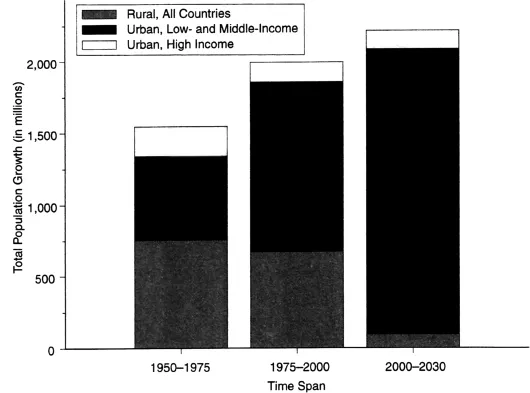

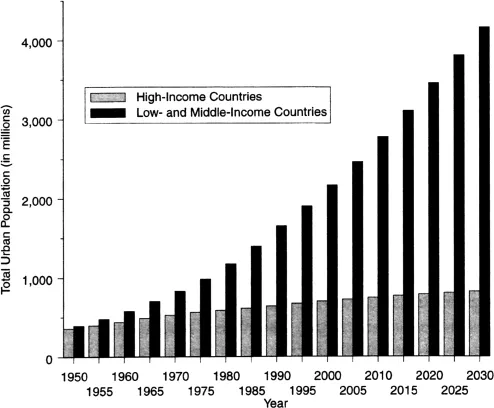

As Figure 1–1 shows, over the next 30 years it is the world’s cities that are expected to absorb these additional billions.2 The total rural population is likely to undergo little net change over the period, declining by 30 percent in high-income countries and increasing by an expected 3 percent in low- and middle-income countries. Relatively small changes are also expected for the cities of high-income countries, whose populations will rise from 0.9 billion in 2000 to 1 billion in 2030. Hence, as can be seen in Figures 1–2 and 1–3, the net additions to the world’s population will be found mainly in the cities and towns of poor countries. The prospects for the near future stand in stark contrast to what was seen during the period 1950 to 1975, when population growth was much more evenly divided between urban and rural areas.

FIGURE 1–1 Estimated and projected urban and rural populations, world totals 1950–2030.

SOURCE: United Nations (2002a).

The United Nations predicts that the total urban populations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America will double in size over the next 30 years, increasing from 1.9 billion in 2000 to 3.9 billion in 2030. These changes in totals will also be reflected in the urban percentages. In 1950 less than 20 percent of the population of poor countries lived in cities and towns. By 2030, that figure will have risen to nearly 60 percent. Rather soon, it appears, it will no longer be possible to speak of the developing world as being mainly rural. Both poverty and opportunity are assuming an urban character.

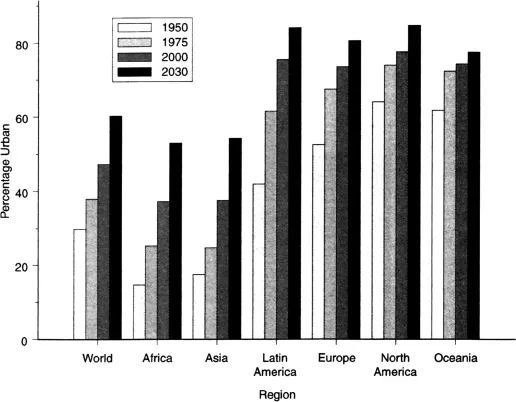

Each of the developing regions is expected to participate in this trend. As Figure 1–4 shows, a good deal of convergence is anticipated, but considerable differences will likely remain in levels of urbanization (the percentage of the population residing in urban areas) by geographic region. Latin America is now highly urbanized: 75 percent of its population resides in cities, a figure rivaling the percentages of Europe and North America. Africa and Asia are much less urbanized, however, with less than 40 percent of their populations being urban. However, Asia will contribute the greatest absolute number of new urban residents over the next three decades. Although both Africa and Asia will become more urban than rural in the near future, they are not thought likely to attain the 60 percent level before 2030.

FIGURE 1–2 Distribution of world population growth by urban/rural and national income level. Estimates and projections for 1950–2030.

SOURCE: United Nations (2002a).

FIGURE 1–3 Growth of total urban population by national income level, 1950–2030.

SOURCES: United Nations (2002a); World Bank (2001).

FIGURE 1–4 Estimated and projected percentage of population in urban areas, by region, 1950–2030.

SOURCE: United Nations (2002a).

A Future of Megacities?

In popular writing on the cities of developing countries, it is the largest cities that receive the most attention. Perhaps it is only natural that cities the size of São Paulo, Bangkok, Lagos, and Cairo come readily to mind when urban populations are considered. Yet for the foreseeable future, the majority of urban residents will reside in much smaller settlements, that is, in small cities with 100,000 to 250,000 residents and in towns with populations of less than 100,000. Data on these cities and towns are scarce and grossly inadequate. No comprehensive, reliable, and up-to-date database exists for cities under 100,000 in population, and as is discussed later, it is even difficult to find data in a usable form for cities under 750,000.

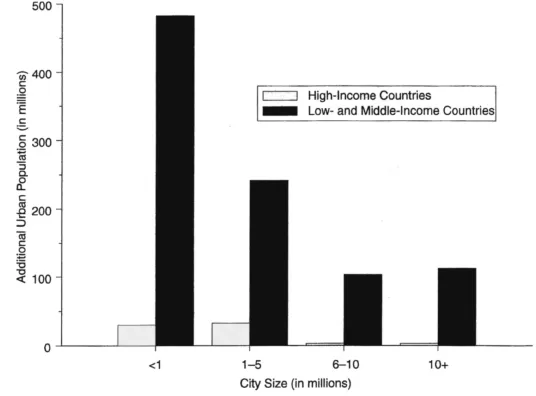

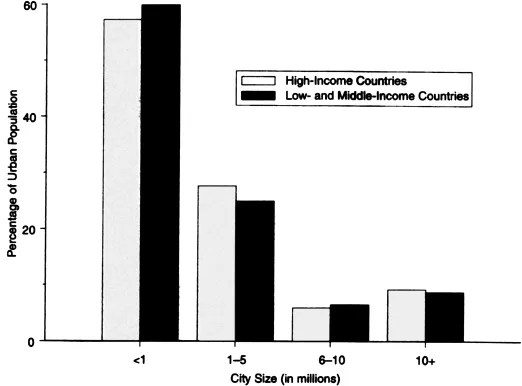

Despite these difficulties, some information on urban populations by size of city can be gleaned from the United Nations (2002a). Figure 1–5 presents the United Nations predictions, showing the number of urban residents who will be added to cities of different sizes over the period 2000 to 2015. As can be seen, the lion’s share of the increase will be taken by towns and cities with fewer than 1 million inhabitants. Figure 1–6 depicts the projected distribution (in 2015) of urban population by size of city. Towns and cities with a population of under 1 million will then account for about 60 percent of the developing-country urban total. Cities from 1 to 5 million in size will house another 26 percent.

FIGURE 1–5 Net additions to urban population, by city size and national income level, 2000–2015.

SOURCES: United Nations (2002a); World Bank (2001).

As a rule, smaller cities tend to grow more rapidly than do larger ones. This tendency is evident in regression analyses with controls for confounding factors, and in the trajectories followed by individual cities over time. To be sure, there is considerable unexplained variation in the relationship between city size and growth. Nevertheless, as will be discussed later, the negative association between the two is sufficiently robust for the United Nations to have incorporated the relation in its forecasting methods.

We cannot recall a case in which a small city was the focus of an editorial lamenting rapid urban growth or the lack of public services. Nevertheless, the combined size of such cities makes them very significant presences in developing countries. As is shown throughout this report, smaller urban areas—especially those under 100,000 in population—are notably underserved by their governments, often lacking piped water, adequate waste disposal, and electricity. Indeed, they can exhibit levels of human capital, fertility, health, and child survival that are akin to those found in rural areas. The sheer scale of the challenges presented by very large cities should not cause the difficulties of these small cities to be overlooked.

FIGURE 1–6 Projected distribution of urban residents in 2015 by city size for high-income countries, and for low- and middle-income countries.

SOURCES: United Nations (2002b); World Bank (2001).

We are by no means suggesting that large cities be neglected in policy and research. The scale on which resources are concentrated in these cities presents governments with needs that are of a qualitatively different order than those of small cities and towns. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were only 16 cities in the world with populations of 1 million or more, and the vast majority of these cities were found in advanced industrial economies. Today the world contains more than 400 cities of this size, and three-quarters of them are found in low- and middle-income countries. For the residents of these cities, scale is a defining feature of social, economic, and political life. It has many positive aspects: when urban activity is appropriately organized and governed, scale can enable specialization, reduce the per capita costs of service provision, and allow economic and social diversity to flourish. In poor countries, however, which lack all manner of the necessary administrative and technical resources, the challenges presented by large cities can be daunting indeed.

In these countries, the proportion of the population residing in large cities is approaching the levels seen in rich countries. In 2000, about one-third of the national populations of rich countries lived in cities of at least 1 million residents. Although poor countries have not yet reached the one-third mark, they are moving toward it. In 1975, only 9 percent of the national populations of poor countries lived in such cities. By 2000, the total had risen to 15 percent, and it is expected to rise further, to 17 percent, by 2015.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF CITIES

São Paulo, now Latin America’s second-largest city and a megacity by any definition, had its origins as a minor commercial center. Although the story of São Paulo has unique elements, it can stand as an example of the changes under way in cities worldwide. In 1890, when Rio de Janeiro could boast a population of more than half a million, only 65,000 people lived in São Paulo. It was improvements in agriculture—widespread coffee cultivation in the region—that ushered in São Paulo’s first era of prosperity. By the early 1900s, manufacturing had gained a foothold in the city, mainly in connection with the processing and marketing of coffee. Over the next half-century, industrialization began on a large scale, a development spurred by the collapse of world prices for coffee, which caused large landowners and major entrepreneurs to scramble for ways to diversify. By 1950 São Paulo had assumed its present position as the leading manufacturing center of Brazil. Industrialization then further accelerated, encouraged by the government’s strategy of import substitution and the construction of a transportation system that made the city a central node. The city’s rate of population growth in this era was truly spectacular—in the 1950s, São Paulo was one of the world’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas. Although its growth rate subsequently d...