![]()

INTRODUCTION

In what is intended to be a very practical book, this chapter will appear to be rather more theoretical than others, but we include it without reservation. We do so for two very important reasons. First, because the research and thinking about learning are yielding insights which help us to construct practical advice on a much firmer foundation than previously. The second reason is because of the fundamental challenge it provides to the more traditional views and stereotypes that prevail about students and learning in higher education.

Teachers have been primarily interested in what and how much students learn, and elaborate assessment methods have been devised to measure these. But in the last quarter of the twentieth century, a considerable body of evidence accumulated which suggested that we need to become much more concerned with how our students learn and the contextual forces that shape their learning. We need to appreciate that some of our students are having difficulties with their studies that arise not just from their lack of application or psychosocial problems, but from the specific ways in which they study and learn. We must also appreciate that many of their difficulties are directly attributable to the assumptions we make about them and the way we teach, organize courses and conduct assessments.

HOW STUDENTS LEARN

Although there has been an enormous amount of research into learning over many years, no one has yet come up with a coherent set of principles that would adequately predict or explain how students learn in any particular context. There have been psychological studies, studies in the neurosciences, in cognitive science, evolutionary studies, anthropological studies, and even archaeological evidence about learning to name a few! The paper by Marchese, available on the Web, provides a fascinating, scholarly and entertaining introduction to all this intellectual effort.

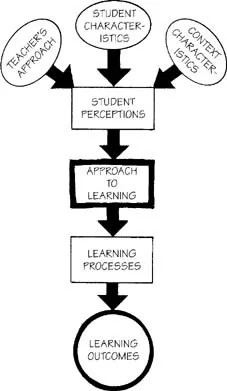

But it was not until 1976 when a landmark study by two Swedish researchers, Marton and Saljo, shifted from the traditional research focus on teachers and teaching to what students actually think and do in real situations. They reported on the approaches students take to their learning. It seems that all students have distinctive approaches to learning that we now understand are influenced by many factors, as shown in Figure 1.1. The

FIGURE 1.1 A MODEL OF STUDENT LEARNING

chain of events in learning and the links between them are the focus of much current research effort and so are likely to be refined over time. We attempt to summarize current understanding here.

One of the factors influencing learning is student characteristics and this includes individual differences, students' previous learning experiences and current understanding of the subject. Other influences can be grouped under context characteristics. This group includes the ethos of the department organizing the course and the characteristics of the curriculum. Closely related to this is the factor of the teacher's approach to teaching (a characteristic we discuss in more detail below).

The effect of these factors is to influence students' perceptions of their context and the learning approach that is expected of them. Students can be observed to use one of three broad approaches to learning, commonly called surface, deep and strategic.

Students adopting a surface approach to learning are predominantly motivated by a concern to complete the course or by a fear of failure. In fact, the emotional aspects of students' perceptions of their context is beginning to receive attention and it is emerging that anxiety, fear of failure and low self-esteem are associated with surface approaches. Surface-approach students intend to fulfil the assessment requirements of the course by using learning processes such as acquiring information, using mechanical memorization (which involves remembering information without understanding it), then reproducing it on demand in a test. The focus of this method is on the material or task and not on its meaning or purpose. The learning outcome is, at best, a memorization of factual information and perhaps a superficial level of understanding.

In contrast, students adopting a deep approach are motivated by an interest in the subject matter and a need to make sense of things and to interpret knowledge. Their intention is to reach an understanding of the material. The process of achieving this varies between individual students and between students in different academic disciplines. The ‘operation learner’ relies upon a logical, step-by-step approach with a cautious acceptance of generalizations only when based on evidence. In such cases, there is an appropriate attention to factual and procedural detail which may include memorization for understanding. This process is most prevalent in science departments. On the other hand, the ‘comprehension learner’ uses a process in which the initial concern is for the broad outlines of ideas and their interconnections with previous knowledge. Such students make use of analogies and attempt to give the material personal meaning. This process is more evident in arts and social science departments. However, another process is that used by the so-called ‘versatile learner’, for whom the outcome is a deep level of understanding based on a knowledge of broad principles supported by a sound factual basis. Versatile learning does not preclude the use of memorization when the need arises, as it frequently does in science-based courses, but the students do so with a totally different intent from those using the surface approach.

Students demonstrating the strategic approach to learning may be seen to use processes similar to both the deep and surface learner. The fundamental difference lies in their motivation and intention. Such students are motivated by the need to achieve high marks and to compete with others. The outcome is a variable level of understanding that depends on what is required by the course and, particularly, the assessments.

The learning outcomes can be broadly described in terms of the quantity and quality of learning. The outcomes that we would hope for from a university or college education are very much those resulting from the deep approach. Disturbingly, the evidence we have suggests that these outcomes may not always be encouraged or achieved by students. Indeed, as we stress repeatedly, there is good reason to believe that many of our teaching approaches, curriculum structures and, particularly, our assessment methods, may be inhibiting the use of the deep approach and supporting and rewarding the use of surface approaches to learning.

NON-TRADITIONAL STUDENTS AND THEIR LEARNING

Institutions of higher education now enrol significant numbers of students (sometimes the majority!) who do not come directly from high school – what is often thought of as the ‘traditional’ source of students. Students from overseas and older students returning to study or entering without the usual prerequisites are just two examples of what we might call ‘non-traditional students’ in higher education.

There has been something of an explosion in the research and writing about these students and their learning. This literature is very revealing. In broad terms, it is showing us that any so-called ‘problems’ with these students is often the result of ill-informed attitudes and educational practices, in short, a result of poor teaching. This confirms the importance of creating a positive learning-environment rather than seeking fault with students.

Students from different cultural backgrounds

One thing we are sure you will have noticed in your institution or from your reading is that stereotypes are attached to students from different cultural backgrounds. One of these stereotypes is that students, particularly from ‘Confucian heritage’ cultures in Eastern and Southeast Asia, are rote learners. Yet many studies have shown that these students score at least as well and sometimes higher than western students on measures of deep learning. You may also have noticed how there seems to be a disproportionate number of these Asian students who receive academic distinctions and prizes.

The ‘paradox’ of these Asian learners – adopting surface approaches such as rote learning but demonstrating high achievement in their courses – has been the subject of much investigation. What is emerging is that researchers have assumed that memorization was equated with mechanical rote learning. But memorization is not a simple concept. It is intertwined with understanding, such as when you might rote learn a poem to assist in the processes of interpretation and understanding. Thus, the traditional Asian way of memorization can have different purposes. Sometimes it can be for mechanical rote learning, but it is also used to deepen and develop understanding. The paradox of these learners is solved when memorization is seen as an important part of the process leading to understanding.

We encourage you to read further about these issues, and about some of the other problematic cultural stereotypes (such as Asian student participation in classes) in the guided reading sources listed at the end of the chapter. They will not only help you to help these students become more effective learners but also provide a deeper understanding about the general processes of learning.

Older students

The literature in this area makes interesting reading. It tells us that older students are generally not much different to the traditional-entry younger students, and sometimes better in important ways. Figure 1.2 summarizes some of the key findings presented in Hartley's book.

FIGURE 1.2 OLDER AND YOUNGER STUDENTS

When compared with younger students, mature students:

- usually perform as well academically, and sometimes b...