![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

The idea of sustainable development

In the last decade a central concept in the debate about future economic progress, nationally, internationally and globally, has been “sustainable development”. Definitions of sustainable development abound. There is some truth in the criticism that it has come to mean whatever suits the particular advocacy of the individual concerned. This is not surprising. It is difficult to be against “sustainable development”. It sounds like something we should all approve of, like “motherhood and apple pie”. But what constitutes development, or progress, for one person may not be development or progress for another. “Development” is a “value word”: it embodies personal ideals and aspirations and concepts of what constitutes the “good” society (see Chapter 2).

Yet, in all the writing on sustainable development there is a common thread, a fairly consistent set of characteristics that appear to define the conditions for sustainable development to be achieved.

The term “sustainable development” itself ought not to occasion much controversy. Development is some set of desirable goals or objectives for society. Those goals undoubtedly include the basic aim to secure a rising level of real income per capita – what is traditionally regarded as the “standard of living”. But most people would also now accept that there is more to development than rising real incomes – “economic growth”. There is now an emphasis on the “quality of life”, on the health of the population, on educational standards and general social wellbeing.

Sustainable development involves devising a social and economic system which ensures that these goals are sustained, i.e. that real incomes rise, that educational standards increase, that the health of the nation improves, that the general quality of life is advanced.

The means of achieving sustainable development in this broad sense might be summarized as follows:

The value of the environment

• Sustainable development involves a substantially increased emphasis on the value of natural, built and cultural environments. This “higher profile” arises either because environmental quality is seen as an increasingly important factor contributing to the achievement of “traditional” development objectives such as rising real incomes, or simply because environmental quality is part of the wider development objective of an improved “quality of life”.

Extending the time horizon

• Sustainable development involves a concern both with the short- to medium-term horizons, say the 5 to 10 years over which a political party might plan and implement its manifesto, and with the longer-run future to be inherited by our grandchildren, and perhaps beyond.

Equity

• Sustainable development places emphasis on providing for the needs of the least advantaged in society (“intragenerational equity”), and on a fair treatment of future generations (“intergenerational equity”).

Chapter 2 elaborates on these three key characteristics and explains why increased emphasis on them is thought to make the process of economic change more sustainable, more lasting.

Annex 1 (p. 172) quotes various definitions of sustainable development and shows how they have the common features of the three key concepts: environment, futurity and equity.

These three concepts of environment, futurity and equity are integrated in sustainable development through a general underlying theme. This theme is that future generations should be compensated for reductions in the endowments of resources brought about by the actions of present generations.

The underlying logic of this proposition is in fact very simple. If one generation leaves the next generation with less wealth then it has made the future worse off. But sustainable development is about making people better off. Hence a policy which leaves more wealth for future development.

Sustainable development as a bequest to the future

The way in which this compensation should take place is at the heart of the debate over sustainable development. Two broad views may be discerned:

(i) compensation for the future is best achieved by ensuring that current generations leave the succeeding generations with at least as much capital wealth as the current generation inherited;

(ii) compensation for the future should be focused not only on man-made capital wealth, but should pay special attention to environmental wealth. That is, future generations must not inherit less environmental capital than the current generation inherited.

Notice that a distinction is being made between two types of capital, or wealth. The first is the wealth with which we are all familiar – capital wealth. This is the stock of all man-made things such as roads and factories, computers and human intelligence. The other form of wealth is natural wealth or natural capital. This comprises the stock of environmentally given assets such as soil and forest, wildlife and water. The two types of capital are not wholly distinct: humans plant forests and breed animals, for example. But the distinction is helpful in understanding what it means when we talk of “environment and economy”, and it become especially important when we look at how the future is to be compensated by the past for losses of natural capital.

The distinction between the two points of view about how to compensate the future is important. For the first allows any generation to degrade natural environments provided man-made capital wealth is substituted for it. The second view does not dispute the importance of wealth creation in this sense, but it insists on the special importance of environmental wealth, the stock of natural assets.

Economy and environment

The philosophy of sustainable development borrows freely from the science of environmental economics in several major respects. A basic aspect of environmental economics concerns our understanding of the ways in which economies and their environments interact.

Fundamental to an understanding of sustainable development is the fact that the economy is not separate from the environment in which we live. There is an interdependence both because the way we manage the economy impacts on the environment, and because environmental quality impacts on the performance of the economy.

The former type of interaction is familiar to most people. The latter, perhaps, is not.

The risks of treating economic management and environmental quality as if they are separate, non-interacting elements have now become apparent. The world could not have continued to use chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) indiscriminately. That use was, and is, affecting the ozone layer. In turn, damage to the ozone layer affects human health and economic productivity. Few would argue now that we can perpetually postpone taking action to contain the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Our use of fossil fuels is driven by the goals of economic change, and that process will affect global climate. In turn, climate warming and sea-level rise will affect the performance of economies.

This two-way interaction is absolutely fundamental to sustainable development thinking. Economies affect environments. Environments affect economies.

The fact that economies and environments interact, and the fact that economic policy devoid of concern for the environment risks both environmental stress and economic damage, may not matter much. We have first to establish that the environmental losses are significant in themselves or that their impact on the economy is significant. Second, even if these impacts are significant, it may pay us to do little about it until later. A problem postponed may be better than a problem tackled now if only because costs incurred later on are preferable to costs incurred now.1 The two issues being raised here are:

• the value of the environment, and

• the costs and benefits of anticipatory policy.

We address each issue in turn:

Valuing the environment

One of the central themes of environmental economics, and central to sustainable development thinking also, is the need to place proper values on the services provided by natural environments. The central problem is that many of these services are provided “free”. They have a zero price simply because no market place exists in which their true values can be revealed through the acts of buying and selling. Examples might be a fine view, the water purification and storm protection functions of coastal wetlands, or the biological diversity within a tropical forest. The elementary theory of supply and demand tells us that if something is provided at a zero price, more of it will be demanded than if there was a positive price. Very simply, the cheaper it is the more will be demanded. The danger is that this greater level of demand will be unrelated to the capacity of the relevant natural environments to meet the demand. For example, by treating the ozone layer as a resource with a zero price there never was any incentive to protect it. Its value to human populations and to the global environment in general did not show up anywhere in a balance sheet of profit or loss, or of costs and benefits.

The important principle is that resources and environments serve economic functions and have positive economic value. To treat them as if they had zero value is seriously to risk overusing the resource. An “economic function” in this context is any service that contributes to human well-being, to the “standard of living”, or “development”. This simple logic underlines the importance of valuing the environment correctly and integrating those correct values into economic policy.

Box 1.1 Environmental problems arising from the absence of markets

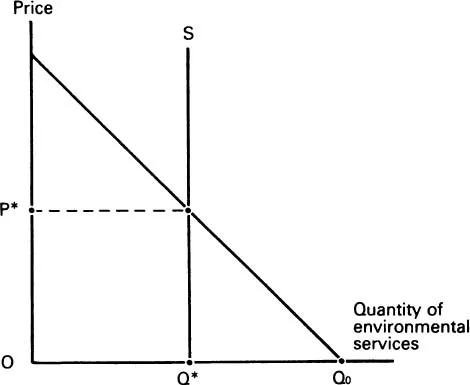

The diagram shows the demand, D, for the services of a natural environment. If there was a price, the demand would be greater the lower the price (imagine an entrance fee to a national park, for example). The supply is generally fixed, however. This is shown by the vertical supply curve, S. If there was a market in the environment in question, price would settle at P* – the “equilibrium price” – and the amount of the environment used up would be Q*. But, in fact, the absence of a market in the environment means that the price is zero and the quantity consumed is Qo. “Too much” of the environment is consumed. This is sufficient to establish the importance of valuing the economic functions of environments. We also need to ask how we can be sure that even a price P* will prevent the environment from being degraded over time.

It is this argument that leads us to reject the first line of reasoning against the emphasis on environmental quality. We have a sound a priori case for supposing that the environment has been used to excess. Its degradation results, in part at least, from the fact that it is treated as a zero-priced resource when, in fact, it serves economic functions that have positive value.

Notice that this does not mean we should automatically introduce actual, positive prices for environmental functions wherever we can. There is a case for “making the user pay”, as we shall see. But for the moment the important principle to establish is that in our economic accounting, in the weighing up of the pros and cons of capital investments and economic policies, we should try, as best we can, to record the economic values that natural environments provide. It is, after all, something of an accident that some goods and services and some natural resources have markets whereas others do not. Even if it is possible to argue that, eventually, all natural resources will generate their own markets,2 we have no assurance at all that those markets will evolve before the resource is extinguished or irreparably damaged.

Box 1.1 illustrates the idea that a zero-priced resource will be “overused” in economic terms.

Anticipatory and reactive environmental policy

A second reason was advanced as to why we may not have to worry about elevating environmental issues to matters of major concern: we may always be able to postpone taking action. One reason for postponing action is that future costs are less burdensome than current costs. This reflects what economists call “time preference” or “discounting the future”. Simply put, we all possess a degree of impatience. We would rather that the new car arrived tomorrow than wait for it for a year. We would prefer our wages or salary now than wait until the end of the week or the month. In a society which is based on letting people’s preferences count, as market-based economies are, it is not logical to accept the role those preferences play in the allocation of goods within society now, while rejecting the preferences that people have for the present over the future.

Respecting time preference is just as much a feature of “consumer sovereignty” as respecting people’s rights t...