This is a test

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing for the Theatre

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Now in its second edition, Designing for the Theatre has established itself as the authoritative introduction to the processes of design for the theatre. Covering the contribution which can be made by costume, sets, props and lighting to a stage production, the author explains the purpose and process involved in their design. Included in this second edition are new photographs and drawings illustrating some of the most exciting and diverse current trends in stage design.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Designing for the Theatre by Francis Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 THE ROLE OF DESIGN

THEATRE DESIGNERS are members of the creative team who bring life, through performance, to a dramatic script and/or score. This team includes:

* Actors who are the primary interpreters of a writer’s words and music.

* Designers whose visual interpretation of script and score costumes the actors and provides a supportive environment.

* Directors who integrate all the individual elements of interpretation within an overall concept, the style of which they have primary responsibility for establishing.

* Audiences who assist a fresh renewal of the interpretation at each performance through their response to the production and their interactive rapport with the actors and with each other.

Whether writers and composers take an active role in the interpretation of their work depends primarily, and obviously, upon whether they are still alive. Even so, their involvement rarely extends beyond the first production and possibly an occasional major revival.

A large support team of enablers help translate creative ideas into performance reality. In particular, the realisation of all visual aspects is dependent upon the interpretative skills of costume, set and prop makers, and technicians.

The prime enablers are producers whose packaging of a production includes the decision to do it, the bringing together of a team and the provision of funding. The producer’s role is essentially one of creative midwifery. During preparation and rehearsals the key enablers are production managers whose organisation of time and money ensures that the production is ready for its first performance, on schedule and within budget. Responsibility for enabling a smooth performance every night, through the integration of acting and technology, rests with stage managers.

It must be emphasised that every member of the enabling team has a creative role. Designers are totally dependent upon the creative skills of all those who are involved in interpreting their designs. Interpretation is more than just a matter of carrying out instructions. Even the most detailed design is still something of a skeletal idea to be developed and transformed during its realisation as a costume, prop, scenic element or lighting balance.

Indeed at no point during the realisation of a dramatic work for performance can anyone respond in a merely passive way. Even when the script includes very specific instructions for how it is to be performed, and when these instructions are faithfully adhered to, the variations between different productions can still be immense. Therefore a designer’s role, like that of everyone working in a theatre (or attending the performance as audience), is one of creative interpretation.

THE DESIGNER’S VISUAL RESPONSE

The designer’s contribution to a production arises out of a visual response to the dramatist’s words and/or the composer’s music. This response will be influenced by discussions with the other members of the creative team. Ideally it would also be a response to observation of character and ensemble development during rehearsal. However, the realities of scheduling normally require irreversible design decisions to be made before rehearsals have even started.

This visual response will most obviously manifest itself in the costuming of the actors and provision of an environment for the stage action. But it should also offer a statement about the play’s intent: a visual metaphor for its verbal philosophy.

This philosophy may not necessarily be a particularly deep or searching one. Theatre offers the possibility of exploring the nature of humanity at all levels, from the fundamental to the frivolous. And to make comment on several levels simultaneously. Even the most lightweight play, apparently seeking only to amuse, offers comment on human frailty that can trigger quite fundamental thinking in an audience.

The designer’s visual response to the nature of the play will be a factor which both influences, and is influenced by, the style of production which the creative team decide to pursue. Visual style will help to determine the nature of the stage environment. But this will also be heavily dependent upon the practical needs of the action. Design should be focused on the need to support the actors: the clothes they wear, the objects they handle and the world they inhabit must support their projection of the characters they play.

AREAS OF DESIGN

Costumes including wigs and make-up, are particularly associated with acting since the clothes an actor wears will both stem from the way a character is played and, in turn, influence the way that the character is played.

Settings and lighting provide a flexible stage environment which can support the play’s progress through time and place. The nature and flexibility of this stage environment is determined by the demands of the text, and by the way in which the chosen production style handles such demands.

Props contribute a link between actor and environment. All objects which the actors handle are classified as props (shortened from properties, a word deeply established in theatre jargon). They are an intrinsic part of the action and are not to be confused with dressing the set by placing objects on it for purely visual effect. Props include everything from furniture and meals to the personal props used by particular characters in the furtherance of the plot (e.g. pens, letters, money, etc.) and costume props which are more in the nature of clothing accessories (e.g. umbrellas, spectacles, etc.).

VISUAL STYLE

Everything placed upon a stage by a designer is conditioned by the visual style which has been adopted for the production. This visual style contributes to, and is derived from, the overall production style which the creative team have chosen for their interpretation of the script. It determines just how the designer dresses the actors and provides them with a stage environment. Conversely, it is the way in which the actors are dressed and the nature of the environment in which they perform that establishes the style. A classic case of interaction!

FOUR-DIMENSIONAL DESIGN

Theatre designers are neither interior designers nor fashion designers. Stage space, stage clothes and stage lighting are not designed for living in, but to provide a visual metaphor for a literary or musical dramatic work and support its communication through performance.

At a purely physical level the theatre designer, handling three-dimensional space and objects within a time progression, is a four-dimensional designer. However, considering the somewhat metaphysical nature of theatre, it would not be difficult to propose additional, more philosophically based, dimensions to a theatre designer’s work.

2 THE THEATRE BUILDING

Before considering production design in any depth, we should give some thought to the nature of theatre buildings. How does the design of a production’s stage environment relate to the total environment provided by the architectural form and function of the theatre in which the production is housed?

Until the present century, the situation was straightforward. Theatre had a standard form and, although this gradually developed, the pace of change was so slow that each generation had a clear view of what constituted a theatre. And they could go to a performance with a clear expectation of a standard production style, familiar in both its acting and its settings.

But in the current century the pace of change has quickened. ‘Theatre’ has been the subject of a great deal of fundamental thinking, and there is now a whole range of theatre building forms simultaneously available as options. Perhaps the easiest way to consider these current optional forms is by a brief historical survey of their evolution.

FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

Changeable scenery did not become a regular part of the actor’s environment until the development of indoor theatre after the Renaissance. And then, for nearly two centuries, the scenery remained a decorative background with little interaction between actor and scene.

Actors in a Georgian playhouse played on a stage which thrust into the auditorium, well beyond the first boxes. Any action of consequence took place forward of the proscenium which was flanked by a pair of doors used for entrances and exits. The close contact with the audience that resulted from this thrusting stage was further emphasised by actors and audience sharing the same auditorium lighting. The actors were thus associated more with the galleried room that was the auditorium than with the scenic background which was restricted to making a pictorial statement of the location of the action.

Although the scenic pictures were not a particularly integrated feature of a production, they did have an important role and indeed their significance for the audience is confirmed by the printing of descriptions on the advertising bills, especially when a scene was newly painted. (A playhouse repertoire was so wide that the basic production design process was one of permutation. New scenes were additions to stock, and although a scene’s initial appearance might well be for a specific play, thereafter it could be called upon to serve any production.)

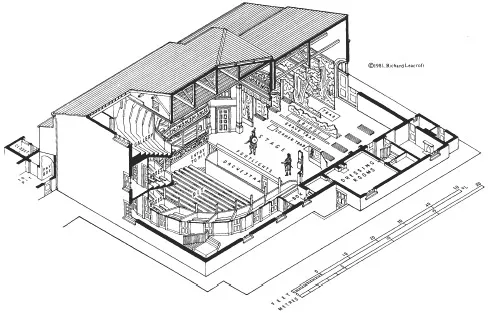

Richard Leacroft’s drawing of William Wilkins’ Barnwell Theatre in Cambridge (c. 1816) reconstructs a typical intimate Georgian playhouse.

Audiences responded positively to perspective painting in a theatre where stage depth could be used to enhance the perspective. We cannot fully know how the audiences reacted but it seems likely that their objective appreciation of the painter’s art was mixed with a suspension of disbelief which, induced by the total atmosphere of the performance, allowed paint and canvas to become reality.

Scenic backgrounds were always accorded more importance in opera and ballet — and indeed still are. Large choruses, and plots hinging upon magic transformations, brought the action into a more integral contact with the scene. But that scene was still a perspective painting whose vanishing point resulted in perfect viewing being possible from only one central position in the auditorium. Nevertheless, the general quality of the painting was such that pleasure could usually be obtained from even the most awkward line of sight.

It was audience preference for a visual theatre that ultimately pushed the actor back into the scene. The managers were happy to accede: apart from a commercial desire (and need) to please the audience, the retreat of the thrust stage increased auditorium capacity.

Scenery took the standardised form imposed by the universal technical architecture of the stage. This provided machinery for locating and changing side wings and overhead borders. Every stage had sets of grooves in which side wings could be slid on and off. The grooves were parallel to the front of the stage and arranged in groups to permit rapid scene changing by replacing one set of wings with another. Changes on the simplest stages were effected by sliding the wings in surface grooves, but in more elaborate theatres, the wings were mounted through the stage floor on a complex system of carriages whose travel could be simultaneously controlled by a capstan.

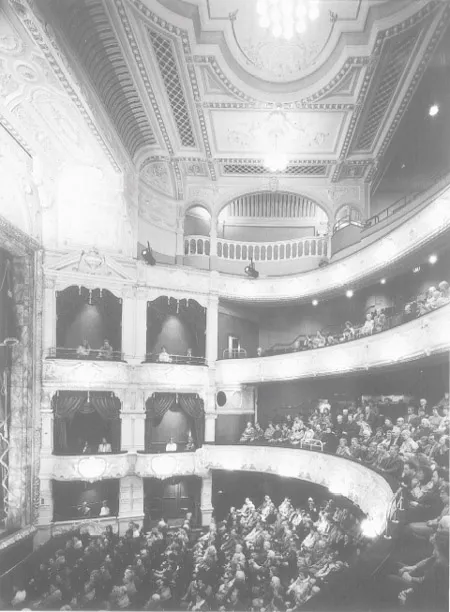

In Frank Matcham’s Theatre Royal in Newcastle (1901, restored by RHWL, architects, in 1987), deep balconies offer most of the audience a clear, although for many a distant, sightline to a stage which has retreated behind the proscenium frame.

Space above the stage was restricted to the minimum required for changing shallow borders, although the more elaborate theatres also had machinery for lowering chariots to carry the gods upon whom so many opera plots depended for resolution. Stage height restrictions were such that any cloths had to be rolled or ‘tumbled’ by raising them in sections; in Britain the rear of the scene was normally a pair of scenic flats, or ‘back-shutters’, which slid on from the side to join at the centre.

The continual need to maximise the financial capacity of the house became the major influence in architectural developments, particularly in Britain where public subsidy did not become available until the middle of the present century. In central Europe, the civic theatres which grew out of the court theatre traditi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Role of Design

- 2 The Theatre Building

- 3 Visual Style

- 4 Space and Time

- 5 Some Practicalities

- 6 The Design Process

- 7 Design Realisation

- 8 Designing with New Technologies

- 9 Learning to Design

- 10 Critical Evaluation

- Some Suggestions for Further Reading

- Glossary of Technical Stage Terms

- Index