- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evaluating and Assessing for Learning

About this book

This study examines the implications for evaluation and assessment when more responsibility for the learning process is given to the learner. The text includes sections on peer assessment, self-assessment, styles of evaluation, references, and the roles of teacher and learner.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1. Needs of the learner

Section 1. Needs of the learner

Introduction

Types of learners

Learning activities

Memorising

Decoding

Creating

Loving

Suggested group activities

Difficulties and criticisms

Annotated biblography

Section 1. Needs of the learner

Introduction

Learning can be related to four theories of teaching:

• Transfer theory where knowledge is treated as a commodity to be transferred from one person to another.

• Shaping theory where the learner is shaped or moulded to a pre-determined pattern

• Travelling theory where the subject is seen as a terrain to be explored; the more difficult hills and mountains help to give a better viewpoint and the teacher is like a travelling companion or guide.

• Growing theory where the intellectual and emotional development of the learner are the focus.

In this book we shall concentrate on the growing theory, but aspects of the other three will be apparent. Learners have not only their own development to cope with but also have to take account of interaction with other people and the ethos of the local and national societies in which they live. There is a tendency towards competence based approaches, particularly in the USA and UK.

Types of learners

Some learners prefer to have information presented to them one step at a time in a linear or serial form. Other learners find learning easier when they can see the ‘whole picture’ to begin with so that they can rearrange the various parts into a pattern which makes sense to them. The former type of learners are often called ‘serialist’ and the latter type ‘holist’.

Serialist learners generally favour linear types of notes whilst holists may favour patterned (or coral) type notes. For this reason, we have provided both styles of summary at the start of each section. However, the patterned notes we have drawn present our own interpretation of the section content. Other people may form a different picture of the content and consequently would produce a different patterned note.

Many learners are able to switch from one style to another, often according to the structure of the learning under consideration. Perhaps this ability to switch could be described as a ‘patchwork’ style. Some learners are only able to operate in one or other of the styles. Do we help them feel more secure with the other style, or do we adopt material and how it is used to the preferred styles of individual learners?

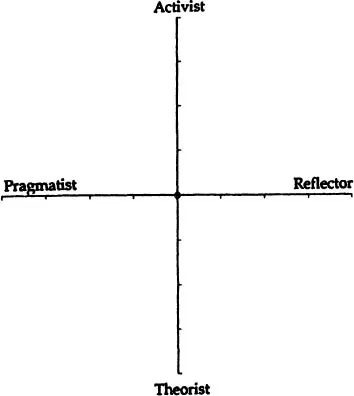

There are many other ways of ‘classifying’ learning style. One which is particularly useful follows from the work of Honey and Mumford (1982). Here, a four-fold classification is used:

• activist

• pragmatist

• reflector

• theorist.

Although some learners will not show bias towards any one style, others may show a strong tendency towards one or more of the styles. Preferred styles can be assessed by using the ‘Learning Styles Questionnaire’. Plotting results on a grid similar to that shown in Figure 1.1 gives a graphic representation of a learner’s preferences.

There are important implications for teaching (ie providing a learning situation). Learners exhibiting different preferred styles are likely to learn more effectively from different situations. For example:

Activists learn best when:

• there are new experiences, problems and opportunities

• they become engrossed in the ‘here and now’

• there is excitement

• things change rapidly

• they lead the learning activities

• they are given freedom in their learning

• they are set challenges.

Figure 1.1 Learner-preference grid

Reflectors learn best when:

• they are encouraged to observe and think about activities

• they can take a ‘back seat’ role

• they are given time to reflect and consider

• they work in a detailed and painstaking way

• learning experiences are well structured.

Theorists learn best when:

• they can organise learning within a personal system or model

• there is time for methodical exploration of ideas and situations

• they have a chance to question and probe

• they are intellectually stretched

• learning is structured with clear aims

• learning appears logical and rational

• they think first, analyse and then generalise

• they are required to understand.

Pragmatists learn best when:

• there appears to be immediate relevance to the learning

• learning is practically biased

• they can practise and apply learning

• they can copy or emulate a model or theory.

Learners may be unaware of their own preferred style and may need help in identifying that which is most comfortable for them. In addition to the ‘Learning Styles Questionnaire’, some of the activities at the end of this section are designed to help identify the preferred learning styles of learners.

In order to encourage learners to try new styles, it is helpful if teachers can use varied strategies of notes and presentations, and persuade learners to try new methods, share their ideas with other learners and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses themselves. Some institutions adopt a policy of all teachers spending time on learning skills and study methods in relation to their own subjects. Other institutions give help during pastoral, tutorial or counselling activities. One of the authors institutions provides a series of free leaflets on study skills to all its learners. The purpose is to help learners to gain confidence in their ability to learn, and therefore to learn more effectively.

We return to the ideas noted above in several parts of the book. In particular, learning how to learn is discussed on page 000.

Learning activities

Let us consider four members of the same family, Pat, Norma(n), Nick(y) and Jo(e). Jo(e) drives a fire engine, Norma(n) is a journalist, Pat is a coal miner operating equipment at the coal face and Nick(y) is a social worker. Each of them uses certain knowledge and routines which they have memorised. Each of them has information and data which they have to decode and use. Each of them has to create solutions to problems. Each of them has to work within a team. So each has the need to meet certain attainments and competencies. We suggest that during learning, learners need to carry out a number of activities, including:

• memorising

• decoding

• creating

• loving.

In a learning context, activity may be in the form of remembering by heart (memorising), reading, selecting and organizing information to write an assignment (decoding), heuristic and creative activities (creating) and working within a group, developing and facilitating group interactions (loving). Let us consider each of these learning activities in the context of a simplified learning experience.

A new stereo cassette deck, amplifier and speakers have been bought by a family. On unpacking the boxes, they find that there are no instructions for operating the cassette deck. On the front panel of the deck are a variety of push button switches, each with a symbol. After connecting the equipment, the family discuss the meaning of the symbols. Each has their own ideas. Norma (whose present the deck is) not only attempts to decode the meaning of each symbol, but also has to decode the often conflicting ideas coming from the rest of the family.

Norma makes a series of decisions, and tries to operate the deck. Some decisions were correct (had the desired outcome) and others were wrong. Further decoding occurs in the light of her experiences. The meaning of symbols becomes clearer and can now be memorised by the whole family.

Jack has just learnt to read. To help him operate the deck, Norma creates a set of simple written labels which she sticks above the controls. Norma has decoded information from a variety of sources, memorised the use of the deck and has used this information to create an alternative set of instructions.

The stereo equipment now works. However, Jack wants his bedtime story tapes played, Norma wants to listen to some folk music whereas both parents want to listen to classical music. The family need to readjust to a new potential source of conflict: a loving activity!

We consider each of the learning activities in greater depth. They will be referred to at various parts of the book.

Memorising

Drivers of taxi-cabs, buses and coaches in large cities are often required to pass a test of knowledge of streets, one way systems etc. Such a test may be required annually. Pilots of passenger aircraft are required to remember routines both for regular activities and for emergencies. Musicians, typists and sportsmen are required to remember sequences and positions of body, hands and fingers to enhance speed and accuracy. Linguists need to learn vocabulary, master grammar and syntax. Actors need to remember cues and lines. Lawyers need to remember case histories.

Many facets of our lives require immediate recall of facts, sequences of ideas or physical actions. Although memorising and rote learning are becoming less popular in current educational thinking, there are still many requirements for memorising; it is in the context of meaningful rote learning and memorising that this section is elaborated.

The learner needs routines, changes to maintain interest, techniques for learning (which have to be adapted to each individual), assignments and assessment. The teacher needs to add to these interactions, systematic evaluating of problems, successes, and new ideas in order to modify present strategies and identify future ones. It is clear that assignments, assessing and evaluating are a crucial part of the negotiated process of learning between teacher and learner. They are a part of the means of providing immediate short term motivation for the learner, and feedback for learners and teachers.

In memorising or rote learning of knowledge, a variety of strategies can be adopted, for example:

• mnemonics (eg. ROYGBIV colours of the visible spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet)

• picture storage (eg. where a familiar room/scene is remembered and facts are located in particular drawers, or on a particular tree)

• using numbers (eg. where the person remembers numbers better than words and associates ideas with number sequences in order to recall them).

These mechanisms are used in order to overcome the limitations of the human memory. In over-simplified terms the human mind can recall about seven different items for discrimination at any one time. In order to extend the memory we group, classify and cluster: remembering seven classes of things, the first is subdivided into say four, and so on. The classification needs to be relevant to the learner, and to that being learned (for example many actors find lines easier to remember when they are associated with actions, intonations).

The types of assessment most applicable for memorising include:

• true/false questions

• multiple choice questions

• repetition (eg. being required to write in extended form that which is provided)

• completion questions

• essay questions where the assumption is recall.

We consider these in more detail in section 3. For movement (psychomotor) learning, assessment may involve accurate repetition at increasing speeds or levels of control.

What seems to be important in meaningful rote learning is that the learning makes sense in relation to the experiences of the learner. The examples that we have given relate to people’s means of employment or to enabling them to be allowed to do something (eg. drive a car). In providing a learning situation, a crucial aspect is that the organizer must know the existing cognitive or psychomotor structures for the individual learner (or at very worst for the group) and to use and build upon this. Without assessing and evaluating, cooperating and negotiating with learners the jug is used to fill the glass with meaningless repetition.

Decoding

Decoding is a popular form of learning at some levels, particularly with younger children, in higher education and with learners learning...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Section 1. Needs of the learner

- Section 2. Evaluating: fitting the system to the needs of learners

- Section 3. Assessing for learning

- Section 4. Roles of learners and teachers

- Section 5. Meeting the needs of learners

- General bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Evaluating and Assessing for Learning by Chris Bell,Duncan Harris,Bell, Chris,Harris, Duncan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.