![]()

Part I

1920–1930

The Ground-Breaking Years

Chronology

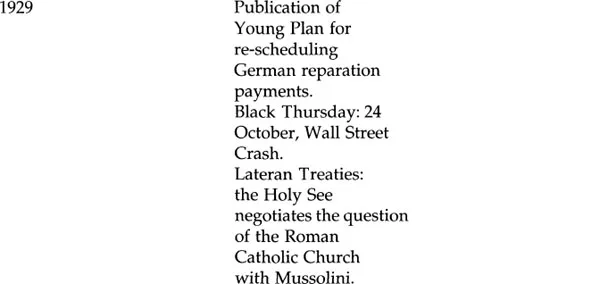

1919–1925: Failed Revolutions and Painful Reconstruction

1920–1930, designated by history and the sidelights on history as the Roaring Twenties, these years are doubtless thus called as a reaction to the long years of the Great War and the train of suffering borne by so many people, the destruction and countless deaths it brought with it. As though, like a strange echo of that horror and absurdity, there took place a sometimes nonsensical permanent fête: certain ties broke adrift, whilst other values found themselves overturned, as is always the case after a catastrophe of this nature. But the effect of this phenomenon is far from negative, for it serves to encourage creativity, audacity and a spirit of enterprise. After a period of convalescence, the early years of this decade saw, in France at least, an economic and cultural leap forward, together with an enormous change in moral habits. French industry experienced considerable growth, particularly in the fields of electricity and car manufacture (this was the age of the supremacy of Citroën). France profited from foreign investments, and her celebrated reputation as a country of the arts and high living attracted many foreigners, especially artists and intellectuals, to settle there. It was in this international melting-pot that the Paris School developed, including such artists as Picasso, Modigliani, Braque, Léger, Chagall, Delaunay, Cendrars and Carco, already resident and active during the war.

In Le Roman vrai de la IIIème République André Fraigneau writes of the Roaring Twenties:

‘These were the years of the negro, the age of jazz, the shift dress, the cropped nape, a tractable form of cubism, sexual daring, gratuitous actions and senseless suicides. The golden calf was still alive, but nobody spoke of it. It was an ox that towered over the roofs of Paris now’.1

Mémories of Fitzgerald. Extravagance was indeed in fashion, the modish sumptuousness of Paul Poiret, kitsch-culture, and the pursuit of ever more iconoclastic activities, such as surrealism and dada; there was, moreover, a ferment, an extraordinary stirring of ideas, within a sometimes unnatural sense of euphoria that did not continue long after the crisis of 1929. The turn of the next decade constituted a turn for the worse, for it must not be forgotten that the rise of fascism was already under way and that economic problems and political insecurity flowered over all the European chess-board.

Dance in the Roaring Twenties

In the 1920s, when this chronicle begins, what was the state of dance in France, and in Paris in particular?

I propose to make only fleeting reference to the Paris Opéra and the ‘great’ dancers and ‘classical’ teachers, but the presence and/or work of some of these were so important that they featured prominently in the scenario and must, therefore, be emphasized:

- The mythical Anna Pavlova, of whom Jean Louis Vaudoyer claimed: ‘Pavlova is to dance what Racine is to poetry, Poussin to painting, and Gluck to music’,2 remained omnipresent, and for a long time after her death in 1931 continued to represent, for many people the world over, the very essence and incorporeality of dance.

- Within the Paris Opéra, where in spite of a repertoire of an obvious academicism and poverty, the excellence of the technical teaching had been maintained. Such eminent figures as Carlotta Zambelli, then at the height of her career, Albert Aveline, ballet-master and teacher Léo Staats, Gustave Ricaux, Ivan Clustine and others, could be found under the direction of Jacques Rouché. It was, moreover, in 1929 that Rouché called upon the young Serge Lifar to replace the ailing George Balanchine, who was to have provided the choreography for Beethoven’s Die Geschöpfe von Prometheus. As a result, Lifar was engaged as choreographer, principal dancer and ballet-master on a permanent basis.

- After Monte Carlo, Paris had been the favourite home-base of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The years in which they made their greatest impact and experienced their greatest glory occurred before the period with which this chronicle is concerned, however. Their world-shattering début was in 1909 (the Fokine years); 1912 began the Nijinsky years; 1917, the Massine years. By the beginning of the 1920s, the Ballets Russes had lost a little of its novelty and appeared somewhat exhausted. Nevertheless, they went on to produce Sleeping Beauty (Tchaikovsky) in 1921, Les Noces, Renard, (Stravinsky) Les Biches, (Poulenc) and other ballets by Bronislava Nijinska, and, with the arrival of Balanchine, most notably The Prodigal Son (Prokofiev) and Apollon Musagète (Stravinsky), which established a link between Diaghilev and his heirs.

It is well known that on the death of Diaghilev in 1929, the company broke up and was later reconstituted as the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, under the direction of Colonel Wassili de Basil and René Blum.

- The great Russian dancers who came either directly from Russia, as in the case of Olga Preobrajenska, or by way of Diaghilev as Lubov Egorova and Mathilde Kchessinska, opened their respective schools in Paris, and dancers flocked from all over the world to work with them.

- Ida Rubinstein, who had danced with the Ballets Russes since 1909 before settling in Paris, played a role similar to that of Diaghilev as patron, organizer and occasionally star of dance productions almost until the outbreak of the Second World War. She could call upon the collaboration of choreographers such as Fokine, Nijinska, Massine and Jooss, and of musicians such as Ravel, Honegger, Stravinsky and Sauguet…

The Influence of the Ballets Russes (and Waslaw Nijinsky)

To what extent did the Ballets Russes, in its first or second incarnation, influence the development of the new dance that was beginning to emerge? To a certain extent, the opposite was true: both in his writings and in his works (Daphnis and Chloé, for example), Fokine explicitly acknowledged the influence of Isadora Duncan, who opened new horizons for him and enabled him to make a more relevant adaptation of classical vocabulary.

The Ballets Russes, like the Ballets Suédois ten years later, was a melting-pot and point of convergence from which a new musical, graphic, theatrical and choreographic aesthetic exploded in the face of the public.

But was the actual choreographic vocabulary of dance cast into doubt? It seems unlikely, except, of course, in the case of Waslaw Nijinsky who undoubtedly could be considered as the ‘father’ of modern dance. This genius, in his so few choreographies, broke completely new ground, ‘working from the inside’, as the moderns would have said, without reference to the prevalent classical tradition. At the time, in spite of the scandals raised by Faun and Le Sacre du printemps, this revolution and all its implications were not fully recognized as such, especially within the classical context to which Nijinsky perforce belonged.

With regard to the Ballets Russes, there occurred a particular and easily recognizable phenomenon: Diaghilev’s nomadic troop formed an organized company, an institution, that was itself descended from another institution, that bastion of classical dance, the Imperial Ballet of St Petersburg. It held high the torch of choreographic tradition, whilst flirting with the avant-garde (in music and the graphic arts). But the weight of tradition and of the institution seems to have curbed this process of questioning of the very language of dance. In spite of superficial distortions and a few new contributions, the vocabulary, technique and, to a certain extent, the choreographic and creative procedures remained firmly rooted in the impregnable foundations of academic dance.

This fact may explain why the Ballets Russes, whilst representing the most ‘modern’, even shocking, face of dance at the time, was not really so modern in relation to the material of dance itself.

Modern Dance is First and Foremost ‘Individual’

In its first teetering steps, modern dance (‘expressionist’ dance) appears to have been strictly the concern of the individual. This seems logical to the extent that the search for (and discovery of) a new vision and language may only be a matter of the greatest intimacy, and therefore personal and individual.

Vision and language must first of all be tested, incarnated and confirmed by the creator, and only later will they be amplified to the scale and scope of a dialogue or group piece. The ability to rally the cohesion of the group and, from this, form a dance company, depends as much on economic factors as on the strength of the creator’s conviction. This was so in the case of Ruth St-Denis and Ted Shawn who founded Denishawn, and of Mary Wigman and her company also, to mention only two examples. In both cases, these companies were a direct offshoot of their director-choreographer, and formed, in a way, their own personal tool. At that time rather more than today, this type of company remained a strictly private concern, and could afford to take risks in the most extreme cases since only the financial interests (and opinions) of the director, and not those of a body politic, were involved.

Did any antinomy exist, therefore, between institutions and individual innovators, who were, by nature, iconoclastic? The innovators and early pioneers of modern dance were fiercely individual and generally self-financed (as in the case of later ones also, for this situation persisted for some time), and they existed largely on the fringes of the dance world.

Cursed artists? Not so. Simply hard-working people, firm in their beliefs, concerned in maintaining their physical prowess and securing a space in which they could devote themselves to their research. This situation explains in part why there were practically no groups or companies in the sense in which we understand these terms today in France, during those inter-war years in which modern dance was seeking to define itself.

One can hardly speak of French modern dance in this period, but of modern dance in France, for the most important and influential personalities were foreigners.

Isadora, the Symbol

In Paris as elsewhere, the pole-star and leading light of new dance was undoubtedly Isadora Duncan. This was especially true in Paris where she remained most willingly for the longest period in her itinerant life, and was both understood and acclaimed. The 1920s saw her in the twilight of her adventurous, painful and exalted life. She made numerous journeys between Paris and Moscow in order to fulfil her dancing and teaching commitments, and in 1922 she married the poet Sergei Essenin, who committed suicide in 1925. The almost mythical death of Isadora herself came unexpectedly in 1927, a few months after her performance at the Mogador theatre.

Isadora’s name, like that of Pavlova, had already become synonymous with and a symbol of dance for a large part of the general public. It would be superfluous to recall here the extent to which she inspired poets and plastic artists, and shook the very foundations of the dance establishment. There was a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ Isadora.

One of her most ardent French admirers, the writer and critic Fernand Divoire, wrote in Découvertes sur la danse3 in 1924:

‘And so, she continues along the route, always at the forefront, each time starting anew, her whole being at stake. The dance of Isadora follows her life’.

‘For almost twenty years we witnessed the phenomenon of this woman who, in the face of all custom and fallacy, danced alone, her only décor a blue drapery; a saint to art, devoted solely to “making the music heard”, and before her the public clapped their hands, went into raptures, and, in tears (yes, indeed), cried out her name: Isadora’.

‘… We are in the years 1920, 1921 and 1922. With each month that passed, Isadora Duncan appeared, to those who returned each time to see her, more supple and diverse, richer in easy, flowing fluidity, more unexpected and new, renewed … ‘

‘Now we see her resuming this course on which fate has forbidden her ever from settling in one place. She will leave us with the imperishable memory of the greatest genius of our time, of an artist, she who claimed that evening at the Trocadéro: “I am not a dancer and I do not know how to dance. Life itself must be a dance …I know only one dance, and that is the movement of the hands to the solar plexus and the opening and lifting of the arms, as if propelled by some inner force” ‘.

It is well known that Isadora had many imitators; some pale, or pathetic copies of this ardent, inspired original: “Disciples” who adhered in large part to the outer formal or expressive aspect of Isadora’s style: Greek tunics, bare feet, loose hair, ‘natural’ movements, classical music and expressive mimicry.

It remained to penetrate to the very foundations of her dance and, without codifying or mummifying it, to make its principles susceptible to analysis, adaptation and development, and thus to transmission. This was achieved later by other means; Isadora herself simply followed her instinct and would have neither wished nor have known how to apply to her own genius the necessary analytical procedure to go beyond her fundamental discovery: the emanation of dance from inner movement, the expression of the soul through the body. And yet, she expressed such beautiful sentiments in her writings:

‘true dance must be the transmission of the earth’s energy through the medium of the human body … man cannot invent, he can only discover. The Spirit of Dance enters into the harmoniously developed body, carried to its highest degree of energy’.4

In the Wake of Isadora

Isadora claimed of her pupils in the programme of a gala at the Trocadéro written in 1914: ‘ … I believe that, in time, some of these girls will succeed in creating their own dances’. Did Isadora mean (as we may suppose), that she wished to see her heiresses achieve a certain degree of autonomy, having been trained according to certain principles, rather than simply imitating th...